The mine site, shown here in 2014, is just a few kilometres from the Arctic Ocean. All photos courtesy of TMAC Resources

In many ways Hope Bay is evidence of new market confidence. When TMAC went public in July 2015, it was the first mining IPO on the TSX since 2012. When Hope Bay’s previous owner, Newmont, approached Terry MacGibbon (now TMAC’s executive chairman) with the project in late August 2012, MacGibbon was immediately interested – the site came with three known deposits, plenty of previous exploratory drilling, and a huge amount of infrastructure already in place.

MacGibbon recruited Catharine Farrow (TMAC’s CEO) and Gord Morrison (president and chief technology officer) – former team members from FNX, the Sudbury-based mining company MacGibbon started in 1997. “We sort of put the old band back together,” he said. By December, Newmont and the newly formed TMAC had an agreement in principal, and a final agreement in January 2013.

“We knew those types of deposits, and had done a lot of high-grade underground mining at FNX,” said MacGibbon. “We saw that the potential was immense, and moved fairly quickly. We thought, this is like buying Timmins in 1910 – but with a billion dollars of infrastructure already on it.” TMAC raised $50 million in private financing and purchased the property in March 2013.

A view of the Hope Bay mine from above. The portal to the mine is at centre-right, the processing building in the middle and the accommodations are at centre-left.

A view of the Hope Bay mine from above. The portal to the mine is at centre-right, the processing building in the middle and the accommodations are at centre-left.TMAC adopted a management approach that they believed would make Hope Bay a success this time around: “We understand the concept of bootstrapping and just doing things a little smaller with a highly-focused management group,” said Farrow. “Our VPs were very much involved in the technical analysis of the project. I go to site a lot more than you probably have ever heard of a CEO going to site. That’s part of our success. In our opinion, as a small company, we have to be able to do that to ensure that we keep the numbers of consultants and that kind of thing down.”

The Hope Bay area had been explored off and on since the 1970s and was originally explored by BHP Billiton who purchased the site in 1988. The property then passed to a junior joint venture in 1999 and Newmont in 2007. Newmont put $800 million into the site, but in 2012 they placed Hope Bay in care and maintenance.

“Newmont had to make some tough capital allocation decisions,” said Farrow. She explained that despite putting the project on hold, Newmont wanted to see the belt developed, and has worked closely with TMAC to this end. “We were chosen as the management group during an auction process to try to achieve those goals.” Today Newmont is a major shareholder, owning 29.2 per cent of TMAC. “That relationship remains,” said Farrow.

The majority of the components for the modular processing plant arrived on the container ship BBC Elbe in late August.

The majority of the components for the modular processing plant arrived on the container ship BBC Elbe in late August.Space to grow

The Hope Bay property – located 160 km south of Cambridge Bay on the mainland – spans 1,000 km2 and includes an 80 km by 20 km Archean greenstone belt with three known deposits: Doris and Madrid in the north, and Boston to the south. Doris, the first deposit to be developed, is just a few kilometres from the Arctic Ocean.

“There was enough drilling on the three known deposit areas that we could put together a development and mine plan that would support a 20-year reserve life,” said Farrow. “That was one of the truly critical pieces of the puzzle.”

The similarities between the Hope Bay belt and other Archean belts, such as those at Timmins, Kirkland Lake, Val d’Or and Red Lake, has not gone unnoticed, and TMAC is hoping Hope Bay will prove to be a similarly successful gold region.

“We see this as a Timmins or a Red Lake kind of environment, where we’re mining there for generations,” she said. “So what we have to develop now is a pipeline of projects at different development stages that fits with the whole concept of building a multi-generational belt.” TMAC’s plan is to sequentially develop the belt, beginning with Doris, then Madrid, and finally Boston.

TMAC will use standard underground mining methods at all three deposits, primarily retreat long-hole stoping with overhand cut-and-fill.

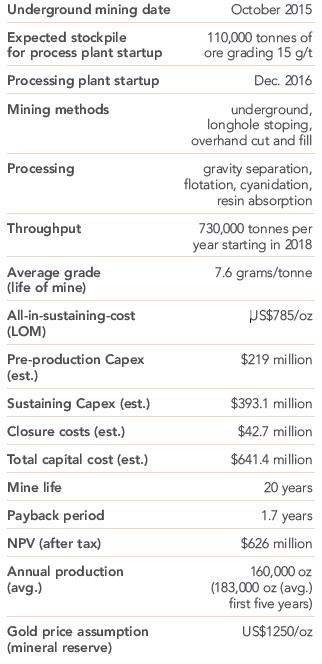

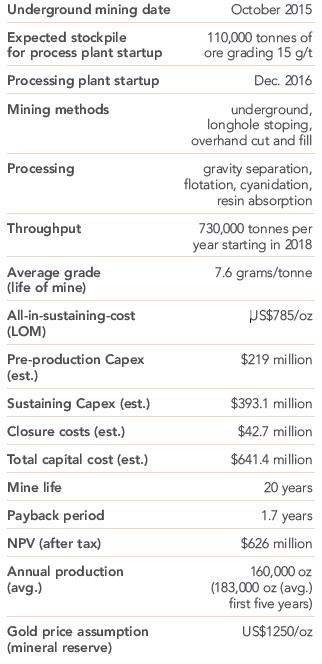

According to Hope Bay’s prefeasibility study (PFS), as of June 2015 the three deposits contain Proven and Probable Reserves of 3.5 million ounces grading 7.7 g/t (and Measured and Indicated Resources of 4.5 million ounces of gold measuring an average of 9.2 g/t). Doris, where the processing plant will be located, contains 870,000 ounces grading 11.8 g/t.

The plant arrived in 200 forty-foot shipping containers.

The plant arrived in 200 forty-foot shipping containers.These reserves are set to grow. Previous owners had planned for open-pit mining, meaning reserves have only been established to depths of a few hundred metres – and just 150 metres at Doris, the point where the deposit hits a diabase dyke. “These deposits have the potential to go one, two, three thousand metres at depth,” said MacGibbon. “So we felt that there had to be mineralization below, and that the potential to add is significant.”

Farrow agrees: “Most of the gold-bearing structures in Archean belts are relatively upright, and continue at depth,” she said. “We’ve been able now to demonstrate that at Doris.” Recent test drilling beneath the diabase dyke at Doris has confirmed additional mineralization (down to 400 metres), officially pushing Doris beyond the initial five years of production indicated in the PFS. Establishing that the resource continued was key, and this success helped the company raise $56.5 million last July.

Farrow also points to Hope Bay’s immense greenfield potential: “If the belt were in more southern parts of Canada it would have been much more thoroughly explored,” she said. “It’s an explorationist’s paradise. There’s so much prospectivity. We’re also really excited by the prospectivity of Boston, but it’s another approximately 50 km to the south. We have to ensure that this is done systematically.”

“We haven’t even set foot on Boston yet,” said MacGibbon, “and in my opinion, Boston is going to be our flagship. But we have to concentrate.” According to MacGibbon, the key to Hope Bay is getting a starter mine up and running. “We have to focus very carefully on getting Doris into production,” he said.

TMAC anticipates the costs leading up to production including items such as permitting costs and environmental bonding, will be a relatively low $325 million. This is due in large part to the amount of previous infrastructure on site, which Farrow calls invaluable. Operating costs are pegged at US$638 per ounce with all-in sustaining costs of US$785 per ounce.

Previous infrastructure includes two gravel air strips, the Doris camp, power plants, 27.5 million litres of fuel storage, underground workings, a tailings facility, a jetty facility at Roberts Bay, a haul road from the port to the Doris camp and an eight-kilometre all-weather road from the camp to Madrid.

“If you include everything that’s been done on the entire belt, including exploration drilling and infrastructure, and underground development, we’re looking at about a billion dollars’ worth of infrastructure,” said Farrow. “Basically what we’ve done is add the last few hundred million dollars.” The bulk of the money has been spent on the building, delivery, and assembly of the processing plant, further underground development and site infrastructure.

A view of the outside of the process building.

A view of the outside of the process building.Modular milling

TMAC also inherited a partially completed processing plant, being built in South Africa. But TMAC instead turned to Gekko, an Australian company specializing in modular plants, which are ideal for shipping to remote locations. The Gekko plant arrived from Australia in over 200 forty-foot shipping containers during the 2016 sealift.

A modular design provides more than just logistical ease with transportation and set-up. “You can’t make things properly modular unless you can shrink them down and get the energy density up,” said Gekko co-founder and technical director Sandy Gray, who flew to site to supervise the assembly. “So we’ve got a much smaller package, but with the capacity to do relatively high tonnes.”

They also have low start-up costs and ease of maintenance. “Because we made every piece less than 20 tonnes, we can now fly in pretty much every single component in the process plant,” said Gray. “So if something big breaks, you don’t have to wait until next summer for a ship to get in.”

The plant also has a greater flexibility, especially with high-grade ores. “Because of the configuration of the plant, we can pretty much handle anything they throw at us,” said Gray. “It doesn’t have the same limitations as some of the conventional circuit processing plants.”

Gekko’s plants make use of pre-concentration and an intensive gravity circuit, through their Python technology. The result, Gray explained, is a lower environmental footprint: “We get a lot of the gold out right up front with the gravity. We use less cyanide because we have a much smaller mass of material that has to get leached, and because it’s in a much more effective form to leach.” TMAC expects the gravity circuit to provide about 50 per cent of the gold from Doris ores.

“We also got the building height down, so we don’t need as much energy to heat the building,” he said. “And by going to a very fine crushing before gravity, we’ve taken out 25 to 30 per cent of the energy of a conventional crushing and grinding circuit.”

The plant, which will have two 1,000 t/d Python pre-concentrator lines, will begin with a mill capacity of 1,000 t/d before ramping up after a year of production to 2,000 t/d. Tailings from the accompanying concentrate treatment plant will be held in a tailings facility, where it will be filtered and eventually placed in the tailings facility, located two kilometres east of Doris.

A view of the process plant building in mid-September.

A view of the process plant building in mid-September.Clear lines

In August, the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB), Nunavut’s environmental assessment agency, approved TMAC’s request to amend their project certificate at Doris. A second amendment under review by the Nunavut Water Board would allow TMAC to increase their tailings from 458,000 tonnes to 2.5 million tonnes, to accommodate an expected increase in production at Doris.

“We are placing more Doris material in the tailings impoundment area and changing our discharge point of mine water from discharge into a fresh water creek to discharge into the ocean,” said Farrow. “Basically it’s preparing for larger operations than was possible with the original permits.”

Farrow also touts the benefits of operating in the jurisdiction of Nunavut. “It’s a very mature way of looking at projects,” she said of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (NLCA). “We know exactly who owns what land, what is Inuit-owned land, what is Crown land, and it’s very clear who you’re dealing with. That makes it considerably less complicated than most parts of the country.”

Within Nunavut, TMAC deals with the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA), which under the NLCA is tasked with overseeing economic development in the region. KIA has both a 1 per cent NSR and 1.4 per cent of the outstanding shares of TMAC, which MacGibbon said allows both parties to be aligned from both a production and corporate point of view.

The reopening of the mine is good news for the Kitikmeot region, which was hit hard when Newmont pulled out in 2012, leaving northern companies at a loss for contracts.

TMAC has a program aimed at training Inuit workers, and makes a point of hiring Inuit-owned companies to provide services on site. These include Summit Air Kitikmeot, for transportation of mining crews; the Kitikmeot-based drilling company Geotech Ekutak, which has a training program for drillers; KCMD, the Kitikmeot arm of Cementation, which began training underground miners during Newmont’s ownership; and the Inuit-owned Nuna Logistics, which was contracted to maintain the site after Newmont put operations on hold, and which has continued to work with TMAC on reopening the Doris camp and other infrastructure projects.

“Huge numbers of the population in Northern communities are under the age of 15. These people will need jobs, and jobs that train them with transferable skills,” said Farrow. “Certainly entry level jobs are important, but ultimately we want to see young people taking on skilled trades and becoming geologists and engineers and doctors, and staying in the communities.” To this end, TMAC has been hiring summer students who have gone to attend colleges in southern Canada. “They’re the future, hopefully, of mine management,” said Farrow.