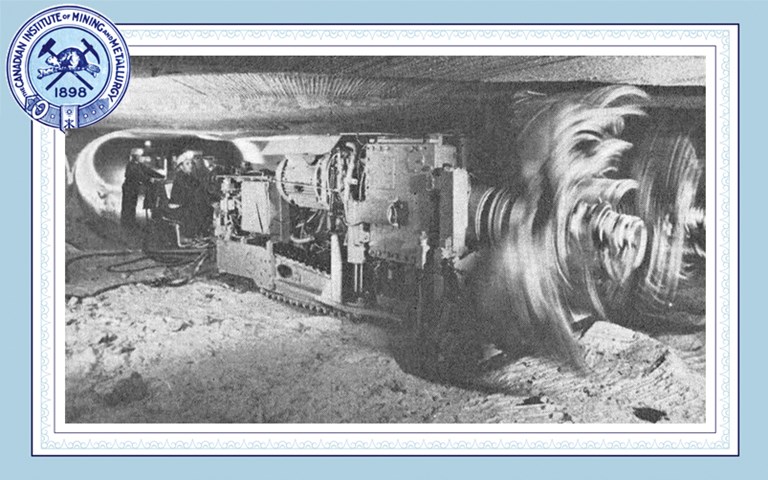

A continuous borer in action at the Esterhazy potash operations (CIM Bulletin, May 1964).

There was no significant North American potash industry until the 20th century, and the majority of imports came from Germany, where potash production began in the early 1860s. W. J. Pearson [CIM Bulletin, October 1960] noted that “up to the outbreak of World War I the German potash industry…was the sole source of potash for North American agriculture and industry. During the war years the United States was forced to get what potash it could from a multitude of expensive sources such as brine lakes, distillery wastes, flue dust, and seaweeds. The price rose from $35 a ton to almost $500 a ton.”

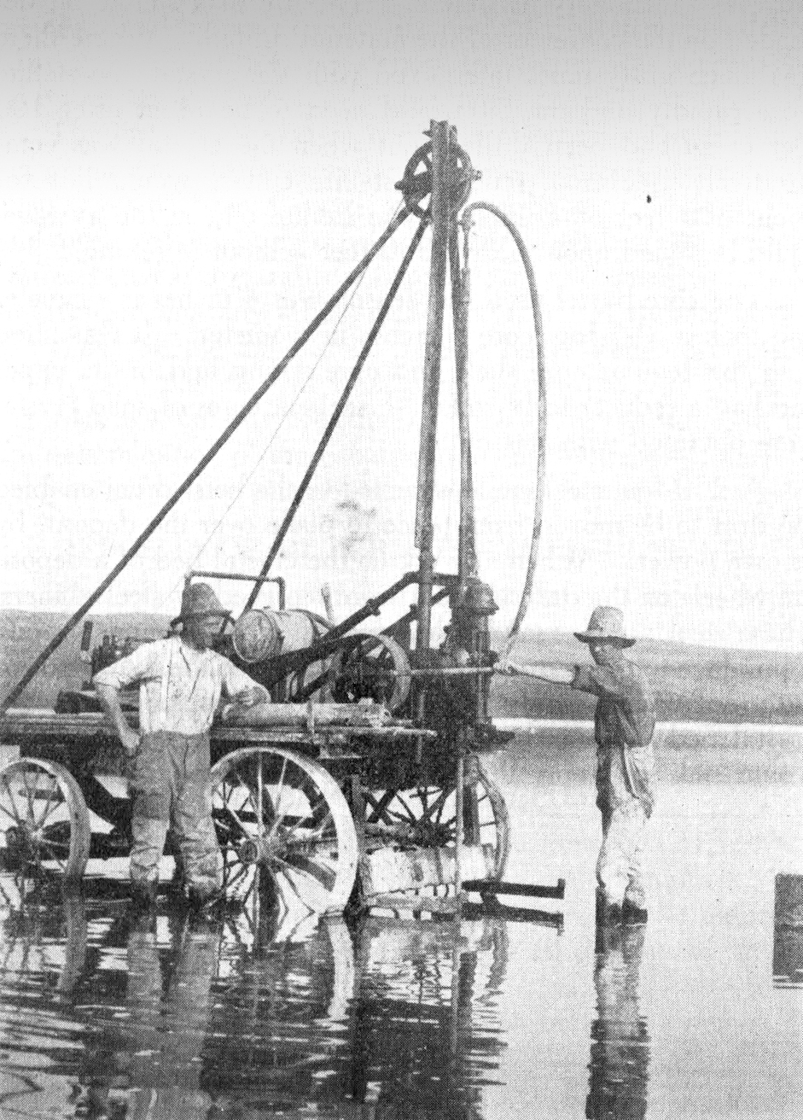

L. Heber Cole [CIM Bulletin, March 1924] said: “The search for potash in western Canada during the years of the great war led to the staking of claims on many of the ‘alkali lakes’ and sloughs which occur in numerous localities in the morainic areas of the prairies, as well as in British Columbia, in the hope that potash salts would be found in commercial quantities.

The Department of Mines using a rotary power drill to test alkali deposits in western Canada in the early 1920s (CIM Bulletin, March 1924).

The Department of Mines using a rotary power drill to test alkali deposits in western Canada in the early 1920s (CIM Bulletin, March 1924).

“During the summer of 1918 a reported discovery of a large deposit of potash bearing salts was featured in western papers and in a short time practically all the lakes and sloughs of the prairie provinces, which showed the least indication of being saline, were staked for potash. This reported discovery was not substantiated on investigation and many of those who had staked claims allowed them to lapse without the slightest effort to determine the character of the material in the deposits which they had leased.”

Discovery and initial production

In 1943, potash mineralization was recognized in core from a hole drilled by Imperial Oil’s subsidiary Norcanols Oil & Gas near Radville in southeastern Saskatchewan, and in 1946, potash core grading 21.6 per cent K20 was recovered near Unity in west central Saskatchewan. “In this well the potash was encountered at a depth of 3,466 feet and speculation was aroused on the possibility of commercial production of potash,” said Pearson [October 1960]. The sinking of the first shaft in the Saskatchewan potash deposits began here in 1952, using conventional shaft sinking methods and grouting.

However, there were some technical difficulties that had to be overcome to mine the significant potash deposits in Saskatchewan. The province’s potash beds are overlain by a number of water-bearing formations that created difficulties during the construction of shafts, the biggest challenge being a poorly consolidated sand-shale-clay-siltstone unit called the Blairmore Formation.

“The ubiquitous and obnoxious Blairmore still lies between the surface and the potash, just waiting to burst in on the unwary miner. For those of you who may not have heard of it, the Blairmore is a sand formation under pressures of 475 pounds per square inch, or more. The Blairmore problems are just for openers. There are a dozen or so more water-bearing strata under it. These have water pressures that exceed 1,000 pounds per square inch,” said Nelson C. White [CIM Bulletin, May 1968].

Great difficulties were encountered during the first shaft sinking attempt at Unity, and the shaft finally flooded with water and sand from the base of the Blairmore Formation in 1961 after reaching a depth of 550 metres. Work on the project was abandoned, and the shaft was sealed in 1968.

In 1954, Potash Company of America began shaft sinking at Patience Lake, near Saskatoon. “The shaft was completed in June, 1958 to the 3,450 ft. horizon,” said Pearson [October 1960]. “Sinking took place through ground that had previously been frozen solid. Pre-freezing was necessary because of the unconsolidated sands and water-bearing horizons in the Blairmore Formation.”

Potash production from Patience Lake began in November 1958 and the first shipment of 1,032 tons was made in March 1959. However, that same year, water began migrating through freeze holes and penetrated the concrete shaft lining, becoming so severe that production had to stop after just nine months so the shaft could be repaired. Fritz F. Prugger and Amfinn F. Prugger [CIM Bulletin, January 1991] noted: “The inflow was not reduced to manageable levels until 1965, when production could finally start up again.”

International Minerals and Chemical Corporation began shaft sinking at a site near Esterhazy in 1957, completing the shaft in 1962 and starting commercial potash production; this is when continuous potash production in Canada began.

During the next eight years, nine more potash mines in Saskatchewan opened: one in each of the years 1964, 1965 and 1967, three in 1968, two in 1969 and one in 1970.

“The first shafts to be sunk in Saskatchewan encountered major problems during shaft sinking. Of the 17 potash shafts started in the province, five had major water inflows during shaft sinking or after production startup, and one was abandoned because of water problems,” said Prugger and Prugger [January 1991].

These technical difficulties are not unique to Canada’s potash mines, however, and Prugger and Prugger [January 1991] noted that “all Saskatchewan potash producers go to considerable lengths to avoid water inflows into underground workings, and procedures to minimize water hazards are employed at all mines…The exchange of information and experience is the cheapest and best investment for long-term cost savings and the protection of valuable resources.”

According to the Mining Association of Canada’s May 2023 report “Economic Impacts and Drivers for the Global Energy Transition,” Canada is the world’s largest producer and exporter of potash. The report said that in 2021, Canada accounted for 31 per cent (22.5 million tonnes) of the total global potash production and 38 per cent (21.6 million tonnes) of the world’s total potash exports.