All but one of Kinross’ operating mines are certified under the International Cyanide Management Institute, including their Fort Knox operation in Alaska (processing plant above). Courtesy of Kinross

Much has changed since the International Cyanide Management Code was implemented a decade ago to help regulate a practice that has experienced its fair share of controversy. To date, 231 operations in 41 countries are certified, representing 60 per cent of global gold production according to the International Cyanide Management Institute (ICMI).

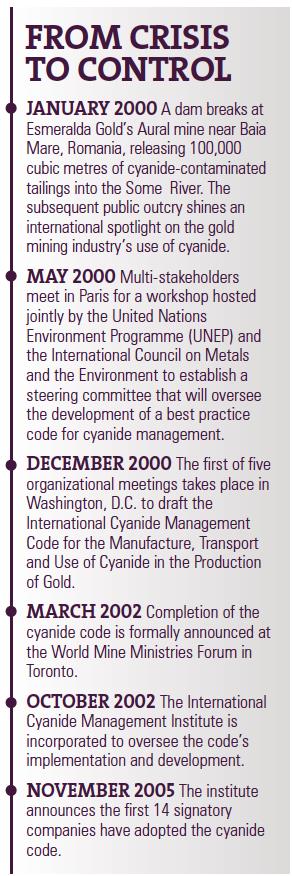

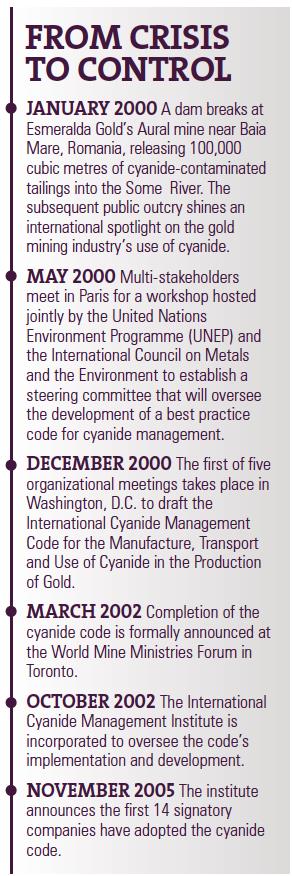

The gold mining industry came under fire after a spill of cyanide and heavy metals from a tailings dam in Romania poisoned waterways in eastern Europe on Jan. 30, 2000. Activists subsequently demanded the illegalization of the chemical in mineral processing – a scenario the industry could not afford to consider. Despite decades of scientific re - search into alternatives like thiourea and thiosulphate, cyanide remains the most efficient chemical for leaching gold.

In May – four months after the Romania incident – the United Nations Environment Programme and the former International Council on Metals and the Environment, along with a number of other stakeholders, met in Paris to establish the ICMI, which would draft and manage the code. Introduced in 2005, the code originally included 14 signatory mining and producing companies. Transporters were not required to become signatories until 2009.

The code is voluntary and gives companies the opportunity to publicly demonstrate their commitment to responsible cyanide management. To become certified, companies must submit an application to the ICMI and have report completed by a qualified thirdparty auditor. It is then processed by the ICMI and posted to the website regardless of the results. For 2014, code-certified gold producers paid a fee of four cents per ounce of gold, transporters US$1,000 and manufacturers US$6,000 to be recognized as signatories.

Paul Bateman, the current president of the ICMI, explained that the code does not eliminate the risk of an accident – in 2010, for example, Newmont Mining agreed to pay US$5 million to the government of Ghana for a cyanide spill at its code-certified Ahafo mine – but its emergency response planning and training procedures safeguard against major spills.

The World Gold Council, the Council for Responsible Jewellery Practice, the International Finance Corporation and the G8 all recognize the code as best practice. Bateman said that even uncertified companies model their operations according to the code’s requirements.

Dean Williams, Kinross’ vice-president of environmental affairs, agreed that the code has become the new industry standard. “Any responsible gold miner of any size that elects not to become certified is actually making a statement that is contrary to most of the industry,” he said. All of Kinross’ operating projects with the exception of its Tasiast gold project in Mauritania are certified.

The ICMI processed 117 applications in 2013, which represents a 50 per cent increase from the previous year. Bateman noted that these numbers are indicative of the program’s growth. To prevent a backup in processing times, the institute hired a fulltime employee in late 2013. The current processing time for a report is, on average, 60 days.

Mines, transporters and manufacturers are certified via a third-party auditor that is knowledgeable in the site- and sector-specific certification requirements. Code auditors are licensed through self-regulating professional organizations like the Canadian Environmental Certification Approvals Board, for example.

“The code’s objective is to bring the mines that are voluntarily adhering to the code up to a certain level of performance,” said Kent Christie, manager of environmental affairs for Kinross. “When an audit occurs, it’s not with punishment in mind if they haven’t got it quite right, but to work with the mine site to bring it up to that performance level.”

While the code remains voluntary, external forces are beginning to limit the choice for many companies. Signatory mines must use certified manufacturing and transportation companies, which has made bidding for large contracts more competitive. Bateman stated that both the International Finance Corp. and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development have incorporated code certification into its lending agreements with mining companies. In addition, Bateman said that being code-certified is another form of due diligence related to mergers and acquisitions.

Companies that become certified have access to ongoing support and training from the ICMI in the proper implementation of the code. The institute also hosts quarterly industrial advisor group conferences where participating companies can suggest improvements to the code. “It was never intended for the code to be a static document,” Bateman assured. “It’s in our best interest to have a system where we can evolve with the best practice instead of locking it in.”