Epiroc’s digital solutions division offers solutions for the digital transformation of the mining industry. Courtesy of Epiroc

In an effort to improve employee safety at its Rosebery underground mine in Australia, global mining company MMG implemented a system in 2023 to actively monitor truck operators’ alertness levels during their demanding 12-hour shifts. At the first sign of distraction, drowsiness or microsleeps, the Hexagon Operator Alertness System (OAS) that had been installed in every operator’s truck sent a notification in real time, allowing MMG to continually assess and address the fatigue risk of its underground crew.

Coupled with operational changes to manage operator fatigue, the results of this digital deployment were especially positive. Not only did severe fatigue events reduce by 81 per cent in the first three months of the program, but overall, sleep events reduced by 53 per cent in one year.

The severity of fatigue events is determined by trained staff at Hexagon remote monitoring centres. No single fatigue event is the same. The operator’s frequency of events and recent operating history are among the factors monitored.

Examples of a severe fatigue event include eye closure without control for three or more seconds and subsequent failure by the operator to recover, or erratic behaviour upon recovery.

The process at MMG also helped foster a culture of safety where employees felt better supported in their jobs with additional health assistance to address fatigue.

The key to MMG’s success for this deployment was understanding that how new technology is rolled out can be as valuable as the technology itself. Rather than simply integrating software systems and processes to improve efficiencies, the company achieved better results by ensuring its entire workforce was on board and supported throughout.

Industry experts say a well-crafted change management strategy—a structured process of planning, implementing and adapting to change—is an overlooked ingredient that often determines if a new digital initiative thrives or dies in the workplace. When people throughout an organization do not buy into change from the onset, they also do not want to invest the extra energy needed to make change happen.

“I refer to the process as adaptation, adoption and empowerment,” said Josh Savit, principal advisor, safety at Hexagon, who worked with MMG on its OAS deployment. Change management is about “ingraining the technologies, solutions and relationships into the overall fabric of the mine,” he said.

For example, he noted that the success of the OAS implementation at the Rosebery mine was incumbent on Savit and his team speaking directly with the mining operators and answering their questions well before the technology was ever installed. “You can’t just say ‘we’re putting this in to combat fatigue and distraction’ because these are just words akin to saying ‘because I said so,’” he said.

Rather, it is important to explain how these terms are defined and how these processes will affect workers in their day-to-day tasks. “Now that camera [in the truck] makes sense as it is only looking at me to see if my eyes are closed or if I’m looking at my screens for too long,” Savit explained. “Knowing why the system was there allowed them to ask questions more directed to their personal needs rather than based on misinformation.”

While some operational disruption at the beginning of a change management initiative is inevitable, Savit said it is about disrupting the workflow to improve it. “You need to change the direction of the river sometimes to make it flow in a better way,” he said.

Resistance to change management in mining

Nathan Stubina, CEO of PACE Global, a Sudbury, Ontario-based company specializing in digital adoption and change management for the mining industry, said multi-million-dollar digital adoptions do not usually fall apart because of technical issues but due to the people side of change and a lack of proper communication.

“We’ve had clients who have tried to implement an initiative for five years, but the iPhone [needed for the project] has been sitting on the shelf because they couldn’t get the miners to use it,” he said.

He also cited a global survey of senior project managers in multinational and government organizations that showed that 86 per cent of their time was spent dealing with people issues. “Leaders think the people part is a soft skill and they don’t need the help to get the project across the line,” he said.

Neha Singh, PACE Global’s founder and vice-president of partner success, attributed the mining sector’s slower adoption of change management protocols—compared to other industries such as health care—to a fundamental gap in how its value is communicated to the decision makers. “First we need to translate change management into what the specific gains will be and then have the leaders who will mobilize it,” she said.

In an industry where operational change is often tied to engineering outcomes or production metrics, Singh believes it is essential to clearly frame the business case for change management in terms mining executives understand—productivity, safety and long-term performance.

MMG’s Rosebery underground mine in Australia implemented the Hexagon Operator Alertness System to continually assess and address the risk of worker fatigue. Courtesy of Hexagon

MMG’s Rosebery underground mine in Australia implemented the Hexagon Operator Alertness System to continually assess and address the risk of worker fatigue. Courtesy of Hexagon

Just as companies have policies and procedures for day-to-day operations, Singh said digital transformations require their own set of policies and processes. “You may need procurement to happen faster during transformation, for example, but the procurement people are the same ones whose mental model is stuck in operations,” she said. “It’s essentially creating a temporary governance model that runs much faster…to resolve risks and address issues, decisions and opportunities related to the change.”

According to Singh, the goal of using consultants in this process is to diagnose the change that needs to be made and ensure everyone is clear about the next steps forward. “You also need a change management company that has the respect of the C-suite and the ear of the board and can say things about operational issues that no one else can,” she said. “We’re coming in to coach your organization’s leaders to learn to lead change because change leadership cannot be delegated.”

Eventually, Singh expects companies like hers will be unnecessary as organizations learn to adapt to continual change themselves. “A manager’s job won’t be just operations, but to truly drive change, and employees will expect change to happen on a continuous basis,” she said.

In the meantime, the more immediate success of change management in mining depends on making sure a company’s entire workforce understands why change is necessary—even if they are not fully on board yet—according to Bob McCarthy, a professional mining engineer and principal consultant at SRK Consulting in Vancouver.

“Whereas the executive team provides the business case for the change, the managers and supervisors provide the technical information to employees and coach them through changes,” he said. “It’s about making sure every individual is brought along and you don’t leave anyone behind.”

Given that change management is not a natural skill set of leaders, McCarthy said it is imperative that there are individuals on site who can “facilitate, train and coach the organization through the change,” whether that be in-house staff or consultants brought in for that purpose. When change management is working well, he said individuals impacted by change are helped through the process to ensure they support the change and gain the needed knowledge and skills to be successful during and after the change—all while minimizing resistance.

Company leaders should also be aware that resistance to change is inevitable and may be particularly challenging in mining, McCarthy added. “People who have run trucks and shovels their entire careers, and those in management positions who are five years away from retirement, may not want to learn something radically different,” he said. “It’s the old saying of ‘what’s in it for me?’”

In the case of in-pit crushing and conveying (IPCC), which has the potential to reduce demand on the haulage fleet, McCarthy pointed to several examples where the technology proved unsuccessful in meeting its intended purpose. “You bring that technology into a mine that has for decades operated trucks and now they have to run conveyors that are inflexible,” he said.

The result at these operations is that IPCCs that were meant to move around a mine site are now parked as permanent crushers. “The benefits of IPCC are quite plain to see and yet you’re not seeing a lot of uptake with this technology,” he noted.

The bottom line, said McCarthy, is that companies that begin a new technology deployment without thinking it through and speaking to their teams will face challenges. “You will incur resistance, it will slow down your implementation and good people might leave, which can be very damaging,” he said.

How to make changes that stick

Sometimes when it comes to big digital transformations, it pays to start small. In the case of its client’s iPhone adoption issue, PACE helped to identify the group of miners who would be most amenable to change and focused on them first. “Instead of saying all miners had to use the iPhone, we found a few who actually wanted to use it on one shift and then the rest of the [shift’s workers] followed because they realized it was saving time,” said Stubina. “Then we deployed it further, one shift at a time—and it worked.”

Change management was a key topic that Ontario-based research company Zero Nexus set out to explore in more detail with the launch of its Electric Vehicle in Mining Operations (EVMO) project in May 2024, which is supported by New Gold, Agnico Eagle Mines, Glencore’s Sudbury Integrated Nickel Operations and Natural Resources Canada’s CanmetMINING group.

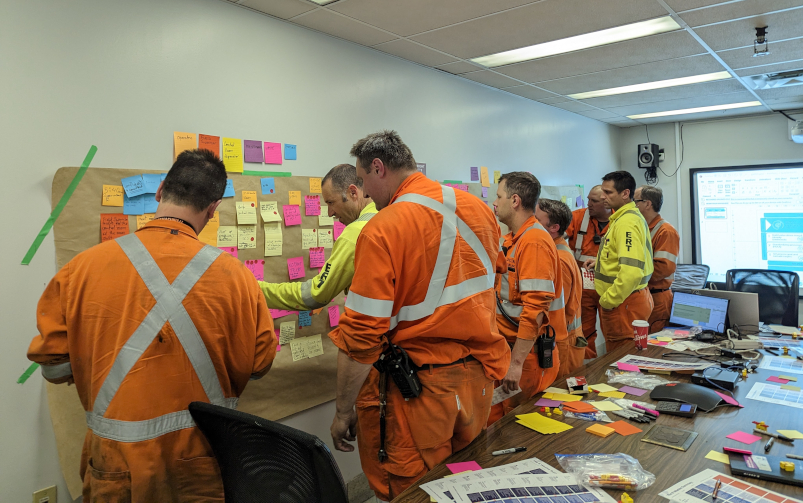

PACE Global recommends that digital transformations at mine sites should have their own set of policies and processes. Courtesy of PACE Global

PACE Global recommends that digital transformations at mine sites should have their own set of policies and processes. Courtesy of PACE Global

“Introducing electric vehicles brings changes to the production environment and maintenance and we wanted to understand how that is navigated by different stakeholders on a [mine] site,” said Edward Fagan, associate partner at Zero Nexus.

In visiting sites using battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), interviewing people in various departments and looking for insights on the challenges they faced in adopting these vehicles, he said the goal was to raise awareness and share learnings to help accelerate change management processes across the board.

In one example, Fagan cited an issue with the production team at New Gold’s New Afton mine in British Columbia around how to improve battery swapping efficiency and the overall availability of charging equipment. The team invested in hiring battery bay attendants who were solely responsible for managing the battery swapping process. Keeping operators in their vehicles rather than swapping the batteries themselves cut the time needed for the battery swapping process by at least a third, which led to three or four extra truckloads per 11-hour shift and easily justified the mine’s investment in attendants. “It was a new role that was introduced to suit the technology but had an improvement in effectiveness and productivity for the system as a whole,” said Fagan.

Another example of effective change management related to the EVMO project was the development of a workforce of dual electrician/heavy duty mechanics who could act as first responders during vehicle troubleshooting. New Gold got the idea for the strategy from the BEV manufacturers, which provide the dual-ticketed technicians to support the equipment as part of service contracts. The idea was to enable more efficient distribution of maintenance/repair activities compared to traditional electrical and mechanical groups, especially given that BEVs introduce more complexity in diagnosing issues compared to standard diesel equipment.

Currently, three mechanics are being trained as electricians (and vice versa) over four years as part of the first cohort of six dual-ticketed apprenticeships at Thompson Rivers University in Kamloops, B.C. “They’ll have these highly trained individuals who will know the mechanical and electrical side of the equipment in detail,” said Fagan. “The benefits they’ve already seen is that these technicians can identify issues as soon as they appear and direct them to the rest of the maintenance team to address.”

In conducting his research for the EVMO project, Fagan said it was interesting to see New Gold diving into its issues and growing alongside the adoption of new technologies. “We saw that a lot of the implementation of strategies was based on the reactions and input of employees,” he said. “The senior leadership supported that change by creating change champions at multiple levels of the organization to take that feedback in and ensure that people on the ground had the resources that they needed.”

The benefits of outside expertise

In helping mining companies successfully deploy change management strategies, it is essential to first understand what the operation is trying to achieve and the hurdles preventing those objectives from being reached, explained Gary Ralph, regional mining advisor at Epiroc’s digital solutions division, which has its Canadian headquarters in Mississauga, Ontario, and offers solutions for the digital transformation of the mining and construction industries.

“We call it a rapid value assessment where we spend one to two weeks on site and then another two to three weeks doing our analysis in the background,” he said. “It’s actually step one in the change management process we utilize because we’re talking to a client about their immediate needs and they can immediately understand what we are proposing to them.”

To minimize disruption, Ralph and his team will often suggest a proof-of-concept or pilot in a representative area of the mine site to deploy the technology initially where it might have the most value. In introducing a new tool or technology, he said companies need to reevaluate their business process and people in terms of training and aptitude, so a pilot provides a more approachable way to do that.

He pointed to a recent multi-million-dollar technology implementation for a Canadian mining client across several of its operations. Epiroc started with one operation, which Ralph admitted was a big learning curve for everyone.

But it was in going through that learning process, and adjusting along the way based on suggestions from Ralph and his team, that the company was able to complete a successful rollout across its sites. “Through improvements in operational efficiencies along the way, they’d already gotten their payback even before we’d gotten to the final site for implementation,” he said.

Change management success stories show that building trust, communicating value and involving employees at every level is the key to optimal technology deployment in mining. After all, when done correctly, change management can do more than facilitate the successful adoption of new technologies—it can build a more agile and digitally fluent workforce better equipped to handle the technology-fuelled changes that are inevitably on the horizon.