The Éléonore mine in the sub-Arctic of Quebec is just one of ten that Goldcorp operators across the Americas, all of which have energy managers devoted to scrutinizing energy consumption on site. Courtesy of Goldcorp

Economic and environmental concerns have miners zeroing in on how much energy their operations require, how much is wasted and how those concerns are changing the thinking on performance measurement.

Energy management is becoming increasingly important for mine sites grappling with rising energy costs and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. According to data from Natural Resources Canada, electricity and fuel costs in the hard rock Canadian mining sector increased 20 per cent between 2012 and 2014, rising from 15 per cent of production costs to 16.7 per cent. Although it can take numerous possible forms, an effective strategy requires an organized approach with top-level support, flexibility on site and widespread buy-in.

The pressure of energy costs – combined with environmental and health and safety concerns – sets a complex task for Goldcorp, which has ten operating mines and three development projects across the Americas. “We’re seeing increases in the cost of energy,” said John Mullally, director of government relations and energy at Goldcorp, “and we’re investing today for mines that will be operating 10 and 12 years from now. There are costs today, and risks that those costs five years, seven years, from now could be significantly more.” Combined with the health consequences of diesel use and environmental GHG issues, in the end, “all those costs end up impacting both on the productivity and the sustainability of business.”

In 2012, Goldcorp set overarching corporate objectives for the following five years on renewable energy (source five per cent of energy from renewable sources), GHG reductions (cut by 20 per cent), and energy efficiency (increase by 15 per cent). In addition, individual mine sites set their own goals. The Musselwhite mine in Ontario focused on optimizing dewatering, improving ventilation and controlling peak electrical demand. At the Peñasquito mine in Mexico, comminution gained efficiency with the installation of a high-pressure grinding roll (HPGR) and blasting techniques that improved the mill feed.

“These recommendations come from the subject matter experts, and in this case the subject matter expert is the dedicated energy manager [at each site],” said Mullally. “The creation of a dedicated energy manager has meant that there’s a central point person who’s accountable for energy consumption, which means that we’ve got better oversight and better traction with respect to energy conservation.”

The ventilation on demand system at Eleonore includes personnel tracking using hard hats equipped with RFID tags to ensure ventilation is concentrated only where it is required. Courtesy of Goldcorp

Culture of conservation

The energy manager brings energy awareness to bear on every area of the business, large and small. “Halogen lights will consume ten times the power of an LED light,” said Mullally. “In a facility that’s as energy-intensive as a mine facility, that’s a difference of hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.”

Just as importantly, the energy manager at a site is also responsible for creating a culture of energy awareness among employees. Andrew Cooper, energy specialist at New Gold’s New Afton mine in British Columbia, thinks this aspect of energy management is underrated. “We’re going through a phase where people are focused on the sexy side of energy management,” he said. “They look at renewables, and they look at new technology and big data and all of this stuff that’s out there now.” But some of the biggest savings come from basic conservation habits – things as simple as deciding to turn on the cold water faucet instead of the hot.

“The other stuff’s important, don’t get me wrong, but I think people are losing touch with the basics,” he said. “They substitute their current power with renewable power and then they still waste it.”

Energy awareness was a major part of New Afton’s ISO 50001 implementation, which started in 2013 and culminated in certification for the international energy management standard in 2014. Since then, the time spent on generating energy awareness has barely receded, according to Cooper. “Every year there’s different groups of people who need different training, different updates in what they’re doing. So it doesn’t really diminish. And we find we have to maintain the same sort of focus and try and come up with new and exciting things to keep it interesting.”

One fun awareness campaign held at New Afton in 2016 was suggested by one of the energy team members. FLIR Systems makes a thermal imaging device that can plug into the bottom of a smartphone. “We bought a whole bunch of these, and we set up a big awareness campaign and encouraged people to borrow them and check what’s losing energy in their home,” said Cooper. “Their windows, their doors, their hot-water heaters, their furnaces, etc.” Employees were able to share these pictures with one another over SharePoint. “That’s quite an exciting campaign, and we’d like to believe that it’s helping people create awareness of energy at home, which rolls over into the workplace.”

When employees get involved, they start coming up with ideas. A mechanic at New Afton suggested adjusting compressor set points, which resulted in a 0.9-gigawatt (GW) annual energy saving. “That was a zero-cost thing that one of the employees undertook himself,” said Cooper.

Compressed air management is low-hanging fruit, an obvious source of energy wastage with low-capital solutions. When Goldcorp campaigned to reduce waste from worn-out components on air compressors at its Red Lake mine, the main challenge was getting everyone aware and proactive. “Even if it’s cheap in terms of capital, it requires a lot of coordination,” said Mullally. “And the energy manager is responsible for rolling out the initiative, communicating, following up with respect to results, and in some cases, awarding and incentivizing these types of things with prizes.”

At the other end of the cost spectrum, Ventilation on Demand (VOD) requires major investments in systems and software, but brings significant returns by turning on fans only when they are needed. “We spend $25 million per year to ventilate our underground mines in Ontario,” said Mullally. “That’s a serious expense. Fifty per cent of our electricity consumption at our mine sites in Ontario is from ventilation. So any initiative that can address the consumption of electricity through ventilation is a big win.” Goldcorp’s Éléonore mine was built with VOD and the same is planned for its Borden Lake mine.

The capital-intensive projects, however effective, are out of reach for many mines. Mary Stewart, executive director of the Australian consultancy Energetics, said that access to capital was a key limitation for smaller companies. “Some of them are not able to afford the big solutions,” she said. Ironically, Stewart remarked that it is smaller companies that are more likely to innovate, yet have the least capital available to do so.

Efficiency measures at New Afton included: the switch to LED lights, adjusting compressor set points to save 0.9 GWh per year and flotation blower optimization, which saved another 1.4 GWh per year. Courtesy of New Gold

Renewable energy

Renewable generation projects have gained traction globally. Installing renewables helps hedge against future energy costs and ensure supply in jurisdictions with no access to the grid.

In Canada’s Far North, a wind farm at the Diavik diamond mine has been leading the way since 2012, offsetting the demand for diesel fuel. Glencore also installed a single wind turbine at its Raglan nickel mine in 2016. That same year, Sandfire Resources installed a solar power facility at its remote DeGrussa copper-gold mine in Western Australia. The $40 million project will supply about 20 per cent of the mine’s annual power, supplementing the existing diesel generating station.

“With battery prices coming down, those hybrid systems are becoming very competitive with both off- and on-grid energy sources,” said Stewart.

Moreover, Stewart noted, “Once you pay off your renewables, you essentially have free energy. That means that you can extend your mine life because you have access to very cheap energy at a point in time where your ore grade is low, and you can still afford to get that ore to the surface and process it.”

Peak problems

Even for a mine that is on the grid, having a self-contained and cost-effective source of energy could address a new challenge: peak-based pricing.

According to Stewart, electricity markets have shifted from usage charges to network capacity charges. “Capacity-based pricing is encoded for the east coast market in Australia,” she said. “This is the majority of grid-connected electricity in Australia and includes all generators, network operators and retailers. Capacity-based pricing is also present in Canada, the United States, and in Europe to different extents and as a function of the market.”

In this pricing regime, a mine is charged for the capacity required to deliver its peak usage. The cost-cutting strategies appropriate for controlling peaks are different from general usage. For example, peak use often occurs when large equipment is started up. A mine trying to minimize its peak charges would schedule equipment startup for times when it is using less energy elsewhere. It might also put in equipment with variable-speed drives or install soft-start mechanisms on motors. “More sophisticated approaches include site flux analyses and ensuring that your site load is well-managed and not peaky,” she said.

Site managers may not realize this is happening because contracts are typically not negotiated on site. But the finer details and complexities of electricity contracts heavily inform Stewart’s conversations with major ASX-listed companies that form Energetics’ mining client base.

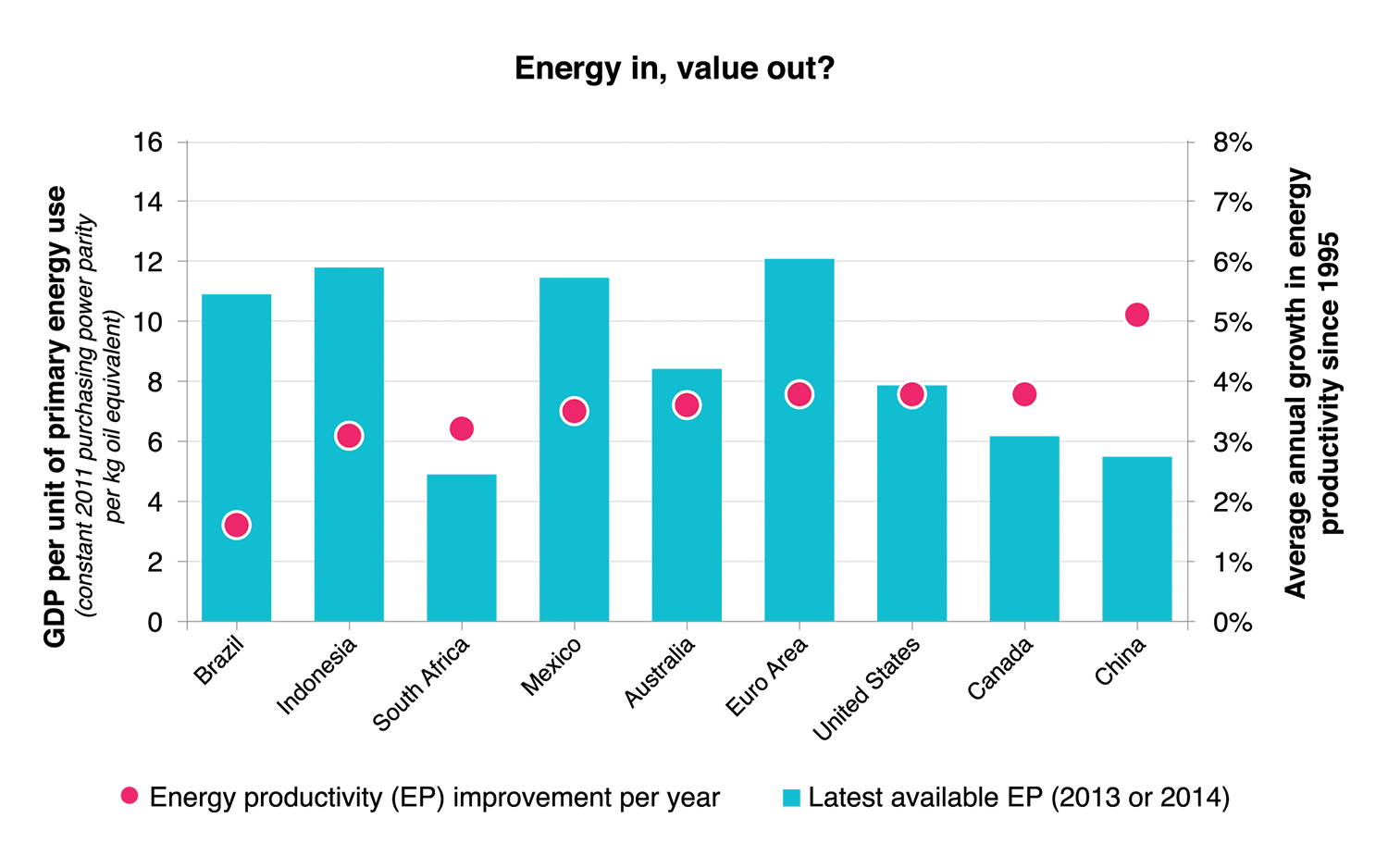

Energy conservation goals are often framed in terms of the energy efficiency of processes or equipment, where the metric is something like “kilowatt-hours (kWh) per tonne of throughput.” Stewart brings a different suggestion to her clients: energy productivity. “What we talk about is dollar of energy invested per dollar of product-value created,” she said. “And that starts giving you a different way of looking at things.” Stewart said there is a movement underway to look at energy saving in these terms in the United States, Canada, Australia, and most recently in South America. “Talking classical energy efficiency is going to become less important because the focus should be on what you’re spending the money on,” she said, “because the charges are going to look different. It’s looking at what your energy dollar buys you, not how much work your energy does.”

Source: Australian Alliance to Save Energy

Energy pricing schemes can take up quite a lot of the energy specialists’ time if they are complex. Ontario’s global adjustment program effectively charges Goldcorp’s mines extra for their usage on the five days out of the year when province-wide usage peaks. Since it is impossible to be sure that an anticipated high-usage day will turn out to be one of the top five, mines that try to control this aspect of their energy costs essentially have to gamble by cutting production on what they think will be peak days.

But Ontario’s pricing scheme can be complicated. “In B.C. it’s pretty straightforward,” said Cooper. “The past three or four years, we’ve actually known what our increases are going to be in advance, which has allowed us to budget for that and we don’t have the global adjustment challenge.”

Cooper said that New Afton’s electricity provider, BC Hydro, does calculate maximum demand, but that it is not adversely affected by motor startups and that energy reduction is not aimed specifically at reducing peaky behaviour.

New Afton’s energy conservation goals are simple as well. Instead of measuring its energy savings in terms of efficiency or productivity, New Afton picked a method that seemed simple and achievable: take the total energy consumption from the previous year, calculate a percentage of that amount, and make that the goal for next year. For example, in 2016, New Afton looked back at its 2015 consumption in kWh or gigajoules, calculated one per cent of that total number, and planned to implement projects that would reduce its 2017 energy consumption by that number – 2.74 gigawatt hours (GWh). Even if the mine’s total energy consumption goes up that year, due to throughput increases for example, the mine would still have realized energy savings from the projects implemented. In 2016, New Afton aimed to cut 2.54 GWh and actually saved 4.5 GWh. “It’s easy to measure, easy to quantify, and we can achieve it,” said Cooper. “It’s a very simple way of doing it. And it works.”

Finding meaningful but realistic goals can be tricky in a continuously expanding and changing mine. “Mines get deeper, rock characteristics change, ore bodies become more or less complex; working out how you are going to predict improvement relative to [your baseline] is very complicated,” said Stewart. “So a simple value that unites everyone is very useful.”

She added that some mining companies are looking at shaping their GHG reductions to the internationally targeted two-degree ceiling on global temperature increase. “It requires significant and absolute emissions reductions,” she said. By taking climate science as a guide, this approach would frame energy saving goals not in terms of what is affordable, but of what is necessary.