Six feet of pure white salt in the Malagash mine (CIM Bulletin, 1924).

“We can speak today of the vastness of Canada’s salt resources, but it was not always so,” wrote H.A. Wilson (CIM Bulletin, 1947). “From at least 1800 onward, the need for a domestic salt industry was clearly recognized by the governments of the day.”

While the existence of salt springs and brine pools in Nova Scotia were well known, there was no large-scale extraction until the 20th century. “Attempts to produce salt were made near Antigonish in 1866, at Black Brook, Cumberland County and at Salt Springs, Pictou County, around 1813, and near Springhill,” wrote A.D. Huffman (CIM Bulletin, May 1968). “All failed or, at best, produced a very small quantity for local use.”

In 1912, a farmer named Peter Murray drilled a well in Malagash, in Cumberland County in northwestern Nova Scotia, while looking for water for his cattle; however, the water was even saltier than seawater. He had discovered the salt deposits of the Cumberland basin, which have thicknesses varying from a few feet to over 1,500 feet, according to Huffman (1968).

Word about his discovery attracted the attention of A. Robert Chambers and George Walker MacKay, two engineers from New Glasgow. They formed the Chambers-MacKay Salt Company (later renamed the Malagash Salt Company) to develop a salt mine at the site.

The Malagash mine

The Malagash mine—Canada’s first rock salt mine—opened in 1918, and the first salt shipments began in 1919.

“Since 1919 there has been a growing production, now amounting to about 5,000 tons per year, from deposits at Malagash,” wrote R.P.D. Graham (CIM Bulletin, 1924). “The salt beds are encountered within 85 feet of the surface.”

This allowed shafts to be sunk into the salt beds, and the salt to be extracted in a solid state (rock salt) using conventional underground mining methods, as opposed to other salt mines in Canada at the time—mostly in Ontario—that extracted salt from brine by evaporation.

“Mining at present is confined to the 200-foot level where a bed of particularly pure salt has been encountered,” wrote the members of the Mineral Resources Division, Mines Branch (CIM Bulletin, 1925). “This averages 15 feet in thickness and is one of four known beds of very pure salt. The estimated total thickness of the whole deposit is 400 feet.”

Chambers (CIM Bulletin, 1924) recorded that there was no definite footwall, hanging wall or cleavage planes at the 200-foot level. “The section is practically a crystal mass for its full known thickness; the few beds of gypsum and interbanded clay being so located that no advantage can be taken of their presence to cheapen mining operations,” he wrote. “This difficulty, however, can be overcome by the use of undercutting machines.”

In 1929, Chambers described the workings of the mine in CIM Bulletin. “There is plenty of head-room, it is electrically lighted, and there is not a stick of timber in the workings, some of which are of huge size and cathedral-like, presenting an appearance at once beautiful and majestic,” he wrote. “The rock salt often resembles ice, though when crushed it becomes white as the driven snow, due, of course, not to any real change in its colour, but to the diffusion of the light reflected from each tiny particle.”

He continued: “The salt is mined and screened very much as is coal, but [with] special screens being used for eliminating the very fine dusty salt made by the explosives and in the crushing operations.”

The members of the Mineral Resources Division, Mines Branch (1925) noted that the rock salt was screened into different grades required for the fish-packing trade, land salt, dairying, ice cream freezing and domestic use.

“The output is carried over the company’s own railway, either to the main Canadian National Railways line some nine miles distant, or a shorter haul of 2¾ miles to the company’s shipping pier at tide-water, where warehouse storage of some 5,000 tons capacity is located,” wrote Chambers (1929). “The salt is transferred from the cars to warehouse, or direct to ship, by elevators and a system of conveying belts, by means of which it may be cheaply and quickly loaded on to either ocean-going steamers or small local craft.”

In 1928, a set of grainer evaporators was added at the Malagash mine. “The bulk of the output still consists of ‘mined’ salt, but recently an evaporating plant has been installed, in which waste material from the mine is converted into ‘manufactured’ salt,” wrote Chambers (1929).

Economic benefits

The development of the Malagash mine was beneficial to Nova Scotia’s economy. “That an ample market is available to absorb the output of a large Nova Scotian salt industry is evident from the fact that Canada is at the present time importing about one-half of the 500,000 tons of salt consumed annually in the country,” wrote Chambers (1929).

The members of the Mineral Resources Division, Mines Branch (1925) noted that the increasing production of salt from the Malagash deposit would materially aid the fish curing industry of the Maritime provinces.

“With the exception of only a small quantity that is exported, the domestic production is disposed of in Canada principally to the dairy, meat-curing, fisheries and chemical industries and as table salt for household,” they wrote. “Until the Malagash deposit was opened, the Ontario district was the only one producing and since it was unfavourably situated with respect to the fishery markets on the Atlantic and Pacific seaboards, large quantities of salt had to be imported. The product from the Malagash deposit has therefore a ready market at hand.”

By 1945, the mine had an annual production of around 38,000 tons of salt, according to Wilson (1947).

“Over the past eight years, Canada’s salt position has changed from utter poverty to untold affluence. Our salt resources are so abundant as to be virtually inexhaustible,” he wrote. “Canadian salt takes second place to none in quality. Our industry goes forward with confidence in itself and in Canada.”

New uses for salt also began to develop. Huffman (1968) wrote, “Since 1950, we have seen the growth of a product, salt, supplying three young markets in Canada—kraft pulp, organic chemicals and highway ice-control. The use of salt for the control of ice and snow will increase.”

Transition to the Pugwash mine

Another significant deposit of rock salt was discovered in 1953 at Pugwash, also in Cumberland County, during the drilling of a water well. The Malagash Salt Co. undertook a drilling program in 1954 that found significant thicknesses of salt. The Malagash mine had been having problems with mining and ore grades, so the company had been looking for alternative salt deposits to exploit.

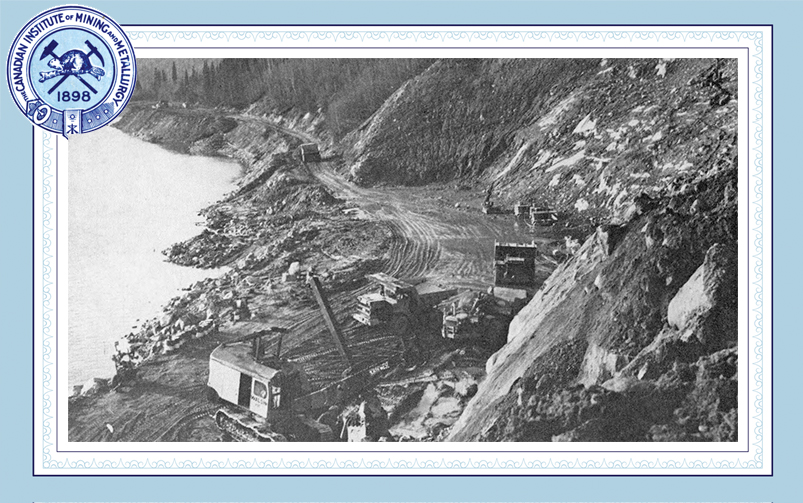

Shaft sinking at Pugwash began in June 1955, according to Lionel A. York (CIM Bulletin, March 1961). “A few months later the shaft reached a depth of 90’, at which horizon large volumes of water and sand entered the shaft and forced suspension of operations,” he wrote. “ln order to combat the running sand, various methods were employed and many attempts were made to deepen the shaft below the 90’ horizon but these were unsuccessful.”

“Late in 1956 a decision was made for The Cementation Company (Canada) Limited to grout and consolidate the formation ahead of the shaft bottom prior to sinking. The first grout treatment was carried out in October of that year and slow progress was made until the upper salt bed was reached at a depth of 360’ below surface.”

In 1958, M.G. Goudge wrote in CIM Bulletin that a mill building, storage facilities, office and a railway siding had already been completed at the Pugwash site, as well as a powerhouse, hoist house and a steel headframe. “Production is expected during the latter part of this year,” he wrote. “The mine at Malagash is currently operating on a reduced basis. This mine will be closed when the Pugwash mine comes into operation.”

D.H. Stonehouse (CIM Bulletin, September 1959) wrote that the new shaft continued to encounter difficulties and that sinking had only advanced 92 feet during 1958. “However, solid material has now been entered, a good bond has been made at the contact, and sinking is progressing very favourably at this date, with intentions to break off a station at the 633-foot level,” he added. “Production continued at the Malagash mine during 1958, but the mine has since been closed.”

The Pugwash mine finally began production in fall 1959. Huffman (1968) noted that the mine used “the room-and-pillar system and large trackless equipment carrying up to 40 tons per load… The face is undercut, drilled and blasted. The broken salt, up to 1,800 tons per blast, is crushed, screened, bagged and shipped.”

The mine has been in continuous production since 1959, and it is currently operated by Windsor Salt Ltd.

The mine produced 581,605 tonnes of finished product in the form of bulk and packaged salt in 2022, according to the Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, of which 467,788 tonnes were shipped for sale. “Most of the finished product was sold in Atlantic Canada and used for de-icing roads,” it stated.