A CN unit train speeding Saskatchewan potash to market in the United States (CIM Bulletin, February 1978).

Saskatchewan, Canada, is currently the world’s leading potash producer and exporter, but this has not always been the case. There was no significant potash industry in North America until the 20th century, with the majority of potash imports coming from Germany.

This changed in 1925, when potash was discovered in Carlsbad, New Mexico. The United States’ first refined commercial potash was produced there in 1932.

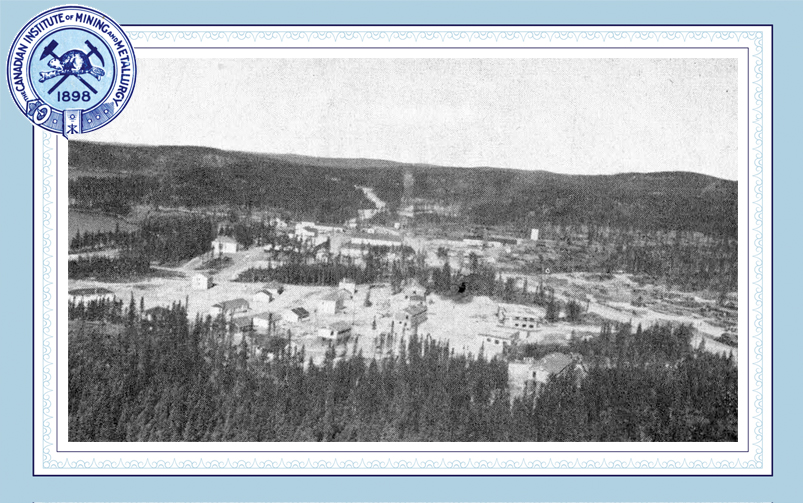

Then, in 1943, significant potash mineralization was discovered in Saskatchewan. First production was in 1958, and potash has continued to flow since 1962.

“The grade of potash found in Saskatchewan is generally higher than the potash being mined in New Mexico and Europe,” wrote W.J. Pearson (CIM Bulletin, October 1960).

Potash markets

The rapid increase in world potash production in the 1960s—mostly driven by Canada—exceeded the predicted growth in consumption; total world productive capacity increased by 139 per cent that decade, noted David L. Anderson (CIM Bulletin, August 1985).

Potash exports through the Port of Vancouver ramped up in 1963 to just under 330,000 tons, and by 1967 had reached around 1,250,000 tons. “Plans for 10 major mining operations suggest a production capacity of 13 or 14 million tons annually by the early 1970s,” wrote G.S. Crawford (CIM Bulletin, September 1968).

According to Anderson (1985), this expansion was due to several factors: “The 1960s were designated by the United Nations as the Development Decade, which focused attention on the world’s food requirements; technological problems had been overcome; the New Mexico reserves were being depleted; the Saskatchewan government required rapid development in order to avoid cancellation of leases; and prevailing K2O [potassium oxide] prices were more than sufficient to generate an acceptable rate-of-return on investment.”

However, this oversupply situation led to a severe decline in potash prices towards the end of the decade. D.A. Karvonen (CIM Bulletin, April 1973) noted that “Canadian prices, which had averaged $37.53 per ton of K2O equivalent f.o.b. mine in 1965, declined in the late 1960s so that by 1969 the average price was $19.87 per ton.”

The decline’s impact was severe in the United States, which by 1969 accounted for 64 per cent of Canada’s potash sales. New Mexico’s potash industry was having difficulties with low prices, resulting in layoffs and the closure of some mines seemingly imminent.

“This led to charges that potash from Canada, France and West Germany was being ‘dumped’ in the United States,” wrote Karvonen. In 1969, its treasury department imposed duties on potash imported from these countries.

The price drop began causing financial difficulty in Saskatchewan too, and by the end of 1969, the Canadian potash industry was operating at less than 50 per cent of productive capacity. The depressed state of the industry was beginning to damage the province’s economy.

“In October 1969, the Government of Saskatchewan announced it would prevent oversupply by regulating the production of potash to market demand by means of a licensing system and that licences would be conditional upon the producer marketing the production at a minimum price,” wrote Karvonen.

Saskatchewan’s Potash Conservation Regulations, commonly known as prorationing, were passed in November 1969 and came into force in January 1970. The aim was to control potash production and establish minimum price conditions. “An immediate result of the program was an increase in revenue to the industry from potash sales,” wrote Karvonen. “In 1970, the first year of prorationing, potash sales were valued at $116 million for 3.4 million tons K2O compared with $69 million for 3.5 million tons in 1969.”

The prorationing scheme achieved its short-run objective, according to Anderson (1985). “In its first year of operation, output declined by 6.7 per cent but total sales revenue increased by 57 per cent,” he wrote.

Karvonen (1973) added that “the increased revenue and guaranteed production level at each mine made all of the Saskatchewan mines viable operations and stabilized employment, thereby helping to maintain the Saskatchewan economy.” New Mexico’s potash industry also rebounded, “thus averting action against Canada in the form of tariffs, import quotas and dumping duties by the United States.”

H.T. Fargey (CIM Bulletin, February 1973) wrote: “The advent of prorationing...cooled protectionist sentiment in the United States. Neither of the bills to restrict imports and assign import duty became law.”

However, there was a strong upward shift in the demand for potash in 1973 and 1974. Anderson (1985) wrote: “As a result…the [prorationing] program had become superfluous and was essentially abandoned in 1974.”

As the potash market strengthened in 1974, the Saskatchewan government applied a reserve tax to the industry, then set up a Crown corporation to acquire ownership by purchase of up to 50 per cent of the industry.

Cost-effective distribution

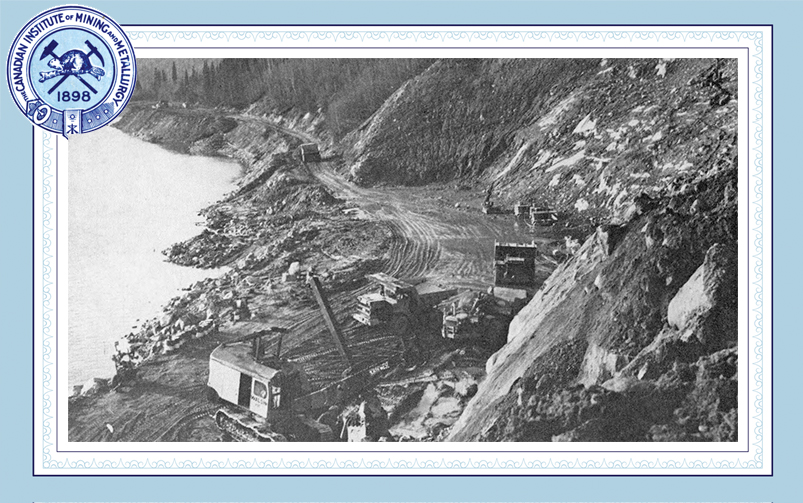

There were also cost challenges in exporting Canadian potash and keeping the price competitive in the global market. Saskatchewan is a landlocked province, with the mines located between 1,600 to 2,000 kilometres from the Port of Vancouver, making transportation expensive due to the long overland hauls required.

“All other competing potash producers are located within 100 miles of deepwater shipping, with the exception of Russia, where direct economic considerations do not appear to be the motivating force behind potash exports,” wrote Kevin B. Doyle (CIM Bulletin, September 1976).

Canadian Potash Exporters (Canpotex) was formed in 1970. It began operating in 1972 as the sole agency for handling Canadian potash sales outside North America, with the aim of obtaining a greater share of export markets.

J.H. Morrish (CIM Bulletin, February 1973) recorded that the railways had worked closely with the new domestic potash industry to encourage its development. “Specifically, spur lines have been constructed to serve the mines and specialized covered hopper cars have been acquired,” he wrote. “These have been significant investments—several million dollars for rail spurs and approximately 110 million dollars for 6,000 cars within the last few years.”

He added that in 1971, an agreement was reached between phosphate rock consumers in Alberta, the two major railways and Canpotex to use the trains to backhaul bulk phosphate rock from the Vancouver terminals to plants in Edmonton and Calgary. The empty cars were then sent to Saskatchewan for return loads of potash.

“Up to 1,500,000 tons of phosphate rock are backhauled in this manner, compared to 3,000,000 tons of potash moving the other way,” he wrote. “This rather unusual and efficient two-way trainload operation is unique on this scale in North America and is an example of a high degree of cooperation among all parties involved, including the carriers, terminals and phosphate rock customers.”

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Canadian potash industry was relatively prosperous. M.A. Upham (ClM Bulletin, March 1980) wrote that for the fertilizer year 1977/78, total shipments of Canadian potash amounted to 11 million short tons, with 2.7 million short tons going offshore through the Port of Vancouver and 8.3 million short tons being shipped to the United States and Canada. He added that Saskatchewan potash was shipped to more than 30 countries in Asia, Oceania, Latin America, Africa and Europe.

By 1984, Saskatchewan accounted for 28, 27 and 42 per cent of the world’s capacity, output and export sales, respectively. Anderson stated: “This level of activity made Saskatchewan the world leader in export sales, and second in capacity and production.”

The present

According to Natural Resources Canada, there are currently 10 active potash mines in Saskatchewan, operated by Nutrien, The Mosaic Company and K+S Potash Canada. These mines produced 24.6 million tonnes of potash in 2022, accounting for 38 per cent of world potash production. Canada exported 21.3 million tonnes of the commodity in 2022, which was 46 per cent of total global potash exports.

BHP is also developing the Jansen potash project in Saskatchewan. Phase one of the project, which is due to begin commercial production in 2026, is expected to produce approximately 4.2 million tonnes per year of potash.

In an economic and commodity outlook released in August 2024, BHP underlined the “attractive fundamentals” offered by Canadian potash. “Demand stands to benefit from the intersection of global megatrends: rising population, improving living standards, changing diets and the need for the ‘sustainable intensification of agriculture,’” wrote the report authors.