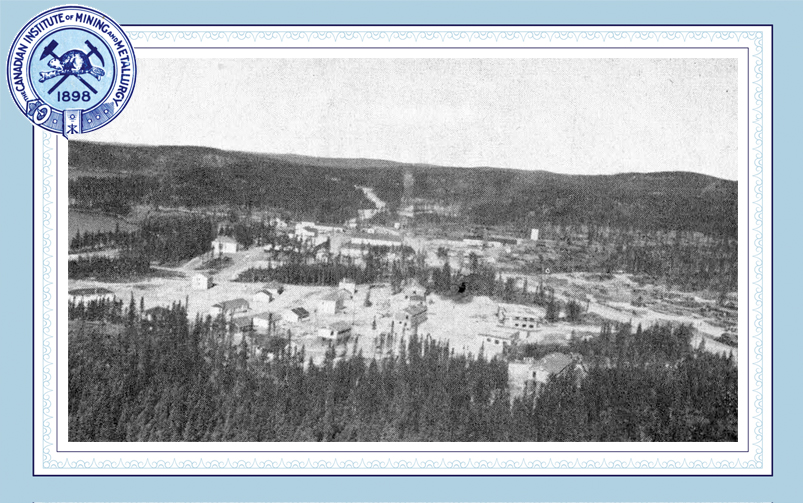

The mine’s bunkhouse, power house, concentrator, change house, machine shop and assay building (CIM Bulletin, 1938).

The Eldorado mine in the Northwest Territories, later renamed the Port Radium mine, was located at LaBine Point on the eastern shore of Great Bear Lake, approximately 440 kilometres north of Yellowknife.

“Attention was first drawn to the mineral possibilities in this district in 1899 and 1900 by J. Mackintosh Bell,” wrote John A. Allan (CIM Bulletin, 1933).

According to Roderick C. McDonald (CIM Bulletin, 1932), prospecting had been prohibited in the area for many years, but this ban was raised in 1930. “The discovery arousing greatest interest was made by Gilbert LaBine, of the Eldorado Gold Mines, on May 16, 1930, while his assistant, E.C. St. Paul, lay in camp, snow blind. LaBine’s discovery was a vein of radium-bearing pitchblende, heavily impregnated with silver,” he wrote.

At the time, radium was in high demand for medical purposes but there were few sources. The majority of the world’s supply came from deposits in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—then a Belgian colony.

“On account of the richness of these ores, the Belgians have practically had a monopoly of the radium industry since they began working these deposits. Even though this is the most recent valuable discovery of radium, this field has already supplied about one-half of the radium that has been offered to the world in useable form,” wrote G.W. Adams and M.S. Stevens (CIM Bulletin, October 1931).

They noted that the radium price was approximately $70,000 per gram in 1931, compared to around $5,000 per gram for emeralds and rubies.

“In view of its stimulating effect on prospecting in the region, the finding of silver and radium by Gilbert LaBine in 1930 on the east coast of Great Bear Lake is probably the most important mineral discovery ever made in the Northwest Territories,” wrote A.W. Jolliffe (CIM Bulletin, 1937).

The Eldorado mine began as a radium operation in 1932. “The years 1931 and 1932 were spent largely in staking, prospecting, and examination of the outcrops,” wrote E.J. Walli (CIM Bulletin, 1938).

D.A.G. Smith (CIM Bulletin, 1938) recorded that mineral concentration began in 1931, and pitchblende and silver from surface pits was hand-sorted and shipped in sacks. “The first gravity concentrator was erected during 1933 and was placed in operation in December,” he wrote. “The initial capacity of the plant was 50 tons per 24 hours. By January 1935 [it had] a capacity of 75 tons per 24 hours.”

Jolliffe (1937) pointed out that the remote location of most of the mines in the Northwest Territories presented a serious hindrance in terms of costs. “For means of transportation, such mines must depend on aircraft,” he wrote. “It is freely admitted by operators in these northern regions that the progress made thus far would have been impossible, and that the country would have remained undeveloped, were it not for air transportation.”

Walli (1938) described how careful planning of the purchase of supplies and equipment for the mine was essential. “Transportation was one of the major problems to be solved, and Eldorado Gold Mines found it necessary to embark upon both water and air freighting on its own account,” he wrote. “The company now operates a Bellanca plane with a payload of 4,400 pounds, and a complete water transportation system.”

In 1932, Eldorado built a refinery in Port Hope, Ontario, to extract radium from the Eldorado mine’s mineral concentrate. “The refinery erected at Port Hope, 4,000 miles away by shipping distance, had completed by November 1936 the production of its first ounce of radium; and the daily capacity of the concentrator has been doubled since 1933,” wrote Charles Camsell (CIM Bulletin, 1938). “The refinery, at which the concentrates are treated for the extraction of radium, uranium oxides and silver, is being enlarged to permit of an output of over 100 grams of radium a year—one-sixth of the estimated amount of radium in present use throughout the world.”

However, the mine closed in 1940; according to D.D. Bell (CIM Bulletin, April 1967) this was due to the dislocation of radium markets during the Second World War.

Uranium demand

The uranium in the Eldorado mine’s ore had been considered to have little economic value as it had few applications, so a lot of it had ended up in tailings. This all changed, however, with the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938.

“When the Manhattan Project for the development of the atomic bomb was started in 1942, the need for uranium oxide became critical, and the only known developed source of it on the American continent was the Eldorado mine, which was closed down at that time,” wrote John Convey and L.E. Djingheuzian (CIM Bulletin, April 1965).

According to Bell (1967), the first uranium supply contract was received in 1942; the mine and its gravity concentrator reopened in March that year, and production began in August. The mine was renamed as the Port Radium mine.

A gravity concentrate was produced at Port Radium from the mine’s high-grade pitchblende ore and shipped to the Port Hope refinery for further processing. “The tailings from this gravity plant operation contained more uranium than the heads of any Canadian mine which subsequently went into production,” wrote A. Thunaes and G.F. Colborne (CIM Bulletin, October 1968).

Due to the new strategic importance of uranium, the staking and mining of radioactive minerals was placed under the Canadian government’s control in September 1943. In January 1944, it nationalized Eldorado as a Crown company.

Even after the war ended, the United States and the United Kingdom still required large amounts of uranium for their nuclear programs. This led to the development of the first modern uranium acid leaching plant at Port Radium.

“Production from the Canadian source had to be not only maintained but increased,” wrote Convey and Djingheuzian (1965). “In addition to looking for new sources of ore, Eldorado asked the Mines Branch (then the Bureau of Mines) to investigate the development of a more efficient method for the recovery of uranium.”

Convey and Djingheuzian quoted P. L. Stevenson’s explanation regarding the direction the research took. “The recovery method used in the earlier operation was of low efficiency, and the tailings, dumped in nearby lakes as useless, had contained considerable amounts of uranium,” she wrote. “It was now realized that this vast store of tailings would yield valuable amounts of the much-needed product which could be reprocessed along with gravity tailings from the newly mined ore, provided that a more efficient recovery method could be devised. As it became evident that physical methods alone could not recover a sufficient percentage of the uranium oxide, the team turned to chemical means, and leaching was investigated as the next step towards full recovery.”

The full-scale plant began leaching gravity tailings and reclaimed dump tailings at Port Radium in May 1952. A.H. Lang (CIM Bulletin, May 1953) reported that the new mill and leaching plant were expected to increase uranium production at Port Radium by 75 per cent.

Thunaes and Colborne (1968) noted that this sulfuric acid leaching process was later modified and applied at all but one of the major uranium producers in Canada.

“One organization which played a key role in uranium extraction metallurgy in Canada was the Mines Branch, later CANMET,” wrote D.M. Ward (CIM Bulletin, December 1989). “It was responsible for developing both the radium extraction process used at Port Hope in 1932, and the uranium extraction process used twenty years later at the Eldorado mine.”

Later life

“At the end of 1959, the first [uranium] boom ended when the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, our biggest customer, announced it would not take up its option on further supplies of Canadian uranium,” wrote M.C. Campbell, G.M. Ritcey and W.A. Gow (CIM Bulletin, March 1985). “By the mid-60s only five mines were in production and exploration was at a standstill.”

In the 1960s, the Port Radium mine transitioned to mainly producing silver. “Echo Bay Mines leased the property in 1964, subsequently purchased it, and have been producing silver and copper ever since,” stated Graham A. Karklin in a presentation at the 13th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Mineral Processors in January 1980.

Echo Bay Mines ceased operations at the site in August 1982. Government figures state that the Port Radium mine had produced 37 million ounces of silver, 10.5 million pounds of copper and 13.7 million pounds of uranium oxide.

According to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), “When the silver mine closed, it was decommissioned according to the standards of the time. Tailings were covered, mine openings were blocked, infrastructure was demolished and all valuable equipment was removed. CIRNAC continues to monitor Port Radium to reduce risks to Canadians and the environment.”