A view of the Tasu townsite, plant site and mine, and the entrance to Tasu Sound from the Pacific (CIM Bulletin, March 1968)

This was one of our favourite stories of the year. To see the full list, check out our Editors' Picks 2025.

The Tasu iron-copper mine was located in the Haida Gwaii archipelago (previously known as the Queen Charlotte Islands) off the north coast of British Columbia, approximately 735 kilometres northwest of Vancouver. The mine was developed on the west coast of north-central Moresby Island, on the south side of Tasu Sound.

According to A. Sutherland Brown, R.J. Cathro, A. Panteleyev and C.S. Ney (CIM Bulletin, May 1971), the Tasu deposit is a magnetite-bearing skarn of the Canadian Cordillera’s Insular Belt. E.J. Wade (CIM Bulletin, March 1968) wrote that the magnetite occurrence was first noted by the Haida people in the 18th century, and that the magnetite-chalcopyrite deposits at Tasu were first explored around 1907 to 1909, following the visit of a prospector named Gowing from Grand Forks to the area in the early 20th century “to investigate the rumour of an unknown metal.”

The deposits were commercially exploited for copper between 1914 and 1917. “During this time, two adits, one stope and an exploratory winze were driven,” wrote Wade.

The site lay inactive for several decades until 1953, when the mineral claims were acquired by Frobisher Limited. Frobisher incorporated a subsidiary, Wesfrob Mines, Limited, in February 1956 to explore and develop the Tasu property.

According to Wade (1968), there had been a political effort for many years to establish an iron and steel industry within the province. “To aid in achieving this objective, legislation was passed in 1951 to prevent the export of iron ore from all but a few properties to which the owners had special title,” he wrote. “By the mid-fifties, this legislation had become unpopular and there were moves afoot to have it rescinded. Moreover, a possible buyer for B.C.’s lump magnetite ore appeared, in the form of the Japanese steel companies.”

By the end of the decade, the provincial government relented and in October 1960, it “removed its restrictive Crown claim to ore reserves and the taxation of iron ore in the ground and permitted the production and export of ore in return for a fair and equitable royalty,” wrote Wade (1968). “At the same time, the Japanese steelmakers were turning to sinter feed for their blast furnaces and this opened an avenue for the use of Tasu’s crushed and concentrated ore.”

Construction

Wesfrob Mines, after an initial drilling program in 1956, began a more comprehensive exploration program in 1961; it was then acquired as a wholly owned subsidiary by Falconbridge Nickel Mines Limited in 1962. “This work, and a detailed feasibility study carried out toward the end of this program, prompted the decision to proceed with development in July 1964,” wrote F.A. Godfrey, H.M.

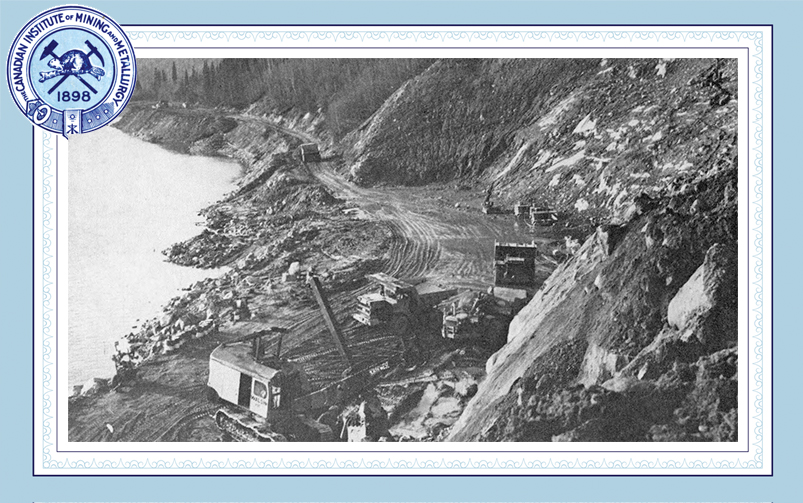

Thurgood and F.W. Gilbert (CIM Bulletin, March 1968). They noted that work began on access roads that November, and this was followed closely by initial pit, plant and townsite excavation.

A company town was built for Tasu mine workers and their families, with 51 housing units for staff as well as facilities such as a community centre with a gymnasium, swimming pool, library and hobby rooms; a three-room school to provide full instruction up to grade 10; and a clinic with doctor’s offices, quarters, X-ray room, dispensary, lab and a six-bed emergency ward.

“The townsite is located on Gowing Island, which is connected to the plant and mine area by a 500-foot-long causeway,” wrote Godfrey et al (1968).

However, the project’s location and topography presented some infrastructural challenges. “The proximity of the mine to the plant site and the steep terrain resulted in many problems, including the necessity of constructing roads at a 10 per cent grade, the close grouping of plant facilities, the limiting of stockpile areas, the lack of storage space and the large amount of excavation required to establish foundations,” they added.

The absence of conventional transportation facilities was also challenging. “The lack of boat service or roads necessitated not only providing barge service to the site from Vancouver but also necessitated the providing of water transport and barges at the site for men and material transport between Moresby and Gowing islands,” wrote Godfrey et al (1968). “During construction, Wesfrob supplied two barges, a water taxi and a small tug for this purpose as well as smaller service boats. The completion of the causeway between the two islands minimized this problem.”

Wade (1968) noted that depending on the season and weather conditions along the coast, a barge trip from Vancouver to the Tasu mine could be as short as 56 hours or as long as 10 days.

Problems with labour availability, the high seasonal rainfall and material escalation meant “construction costs at the site were far above those on the lower mainland,” wrote Godfrey et al (1968). “The necessity of importing construction sand, aggregate and landscaping materials from Vancouver also contributed to abnormal costs.”

Operations

Donald L. Brothers (CIM Bulletin, March 1968) recorded that the Tasu mine opened in June 1967.

Two open pits, Zones 1 and 3, were initially mined, and J.E. Dodge (CIM Bulletin, March 1968) wrote that stripping would start on a third pit, Zone 2, in approximately two years. “Although mining for the first few years will utilize open-pit methods, extensive underground development provided an ore pass, tram and underground crusher system to minimize all trucking of ore,” he added.

Wade (1968) wrote that proven and mineable ore reserves at the Tasu site amounted to 18,500,000 tonnes grading 38.2 per cent iron. “Of this total, Number 3 zone contains 5,200,000 tonnes assaying 44.5 per cent iron and 0.75 per cent copper,” he wrote. “In addition, surface drilling has indicated about 15,000,000 tonnes of probable ore grading 45 per cent iron to the west of the main zones.”

The open pits serviced the primary crusher from two areas via ore pass raises. According to Kenneth Blower (CIM Bulletin, March 1968), the run-of-mine ore was classified as copper-bearing (for Zones 2 and 3) or copper-free (Zone 1), according to its source. “The two types of ore are isolated throughout their treatment,” he wrote. “The grinding and concentrating circuits may be considered as two individual entities—a copper-bearing pellet concentrate circuit and a copper-free sinter concentrate circuit.”

Wade (1968) noted that the Tasu mine’s location in a temperate rainforest with annual rainfall in excess of 160 inches posed further challenges.

“Water has been the major ore pass problem and has produced major spills in the haulage adit and at the primary crusher. Although ore passes making water were grouted during the development program, cracks around the raise collars led to the ingress of surface water,” wrote Dodge (1968). He added that the ore passes were being run as empty as possible at all times to minimize the amount of water in the ore.

Despite the region’s heavy rainfall, water storage was an issue at the site. “Run-off is immediate and the long summer provides a small percentage of the total rainfall,” wrote Godfrey et al (1968). “After considerable study, Wright Lake, four miles to the southwest at the head of Fairfax Inlet, was selected as the only reliable water source… It is noted that the watershed feeding the lake was the supply tapped and not the lake itself.”

While the mine was close to deep water, there were still some challenges related to shipping. “The trend to super ore carriers forces the producer to become involved with the problem of large vessels,” wrote Godfrey et al (1968). “Storage space at Tasu was limited, but large stockpiles were necessary. A natural harbour was available but underwater excavation and dredging were necessary. Local shipping activity was limited, but berthing tugs were necessary. Fewer than twenty carriers were scheduled annually, but high loading rates were necessary. A normally adequate docking area was available, but a movable shiploader was necessary.”

According to Wade (1968), the first shipment of iron concentrate to Japan took place in August 1967.

Godfrey et al (1968) wrote that “Japanese markets consume the entire Wesfrob production of approximately one million tons per year of iron concentrate and 50,000 tons per year of copper concentrate. All sales are arranged by Mitsubishi Shoji Kaisha Limited.”

Underground development at the Tasu mine was completed in 1977; with the exhaustion of ore in the open pits, underground mining was initiated the same year.

With its economic reserves extracted, the Tasu mine closed permanently on Oct. 5, 1983. According to figures from the B.C. government, the mine’s total production from 1914 to 1983 was 23,297,228 tonnes of ore; from this, 1,430,141 grams of gold, 52,822,505 grams of silver and 57,090,466 kilograms of copper were recovered. Iron concentrates totalled 12.35 million tonnes, averaging 65 per cent iron.