The concentrate storage building at the Polaris mine (CIM Bulletin, April 1983).

The Polaris zinc-lead underground mine, which was located on Little Cornwallis Island in Nunavut at a latitude of 75°23’N and at a longitude of 96°55’W, was the world’s most northerly base metal mine.

“In 1964, the Cominco exploration group optioned several Zn-Pb showings from Bankeno Mines Ltd. in the Cornwallis Zn-Pb district,” wrote Iain Mitchell, Robert L. Linnen and Robert A. Creaser (Explor. Mining Geol., Vol. 13, Nos. 1-4, 2004). “Over the next seven years, Cominco conducted geological and geophysical reconnaissance in the district, culminating in 1971 with the drilling program on Little Cornwallis Island that discovered the Polaris orebody on the first hole.”

The Polaris deposit was a Mississippi Valley-type (MVT) orebody. “Reserves consist of about twenty million tonnes of ore grading 3.8% Pb and 14.3% Zn with a further three million tonnes of inferred ore at a slightly lower grade,” wrote J.S. Drake and P.G. Keohane (CIM Bulletin, August 1985).

They noted that initial mine development began when an exploration decline was advanced into the orebody in 1972. “The orebody could be more quickly accessed by underground methods, and it was felt that an underground approach also had the advantage of probably being more able to recover ore near or under saltwater,” wrote Drake and Keohane. “The low cover over the orebody led to accessing through a decline system rather than a shaft.”

Cominco established a twin decline system; one for conveyor extraction of ore, and a sub-parallel service decline for the movement of workers, materials and equipment. “Total pre-production development, including the exploration rockwork, amounted to about 4,500 metres of waste and 800 metres of ore drifting,” wrote Drake and Keohane.

Climate and logistics

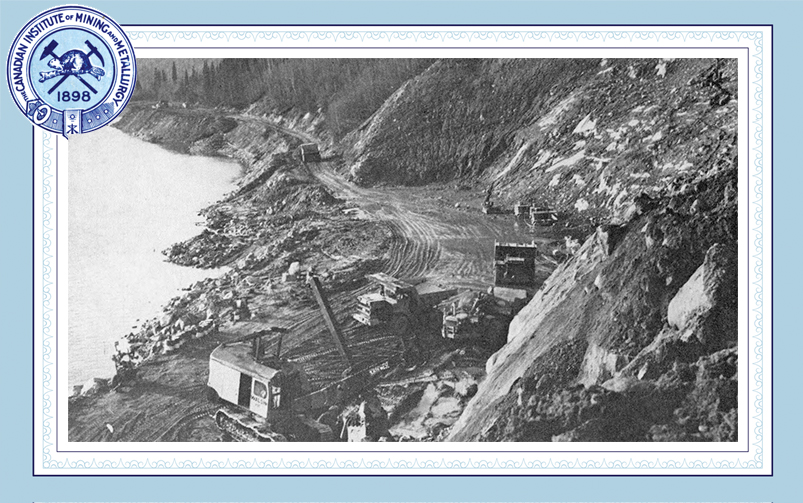

The Polaris mine faced numerous challenges stemming from its extreme northerly location and the harsh Arctic climate. “In trying to minimize the effect of [the harsh environment, short shipping season and high cost of labour], the concept of a barge-mounted process plant was investigated as an alternative to the conventionally built concentrator,” wrote James W. Gowans (CIM Bulletin, April 1983).

The main facilities—such as the concentrator, powerhouse, shops, offices and warehouse—were built on a barge in Trois-Rivières, Quebec, then towed approximately 4,800 kilometres to be beached in a prepared berth on Little Cornwallis Island, on the shore of Crozier Strait.

Gowans noted that the normal shipping season at Little Cornwallis Island was approximately six weeks long, from mid-August to the end of September, and all equipment and materials had to be delivered during this ice-free shipping window.

“The logistics problems are enormous; if the conventional approach had been used the major process equipment would have been delivered to Little Cornwallis Island at the same time as the completed barge actually was,” he wrote. “Construction would also be starting at the start of the worst climatic conditions, the Arctic winter. Nine months’ production was gained by opting for the “barge” approach.”

According to Gowans, the Polaris process barge set sail from Trois-Rivières on July 24, 1981, and arrived at Little Cornwallis Island on August 13, 1981. “By September 3, the generators were producing power for the property and by mid-October 1981, the concentrator was milling waste material for tuning up the equipment,” he wrote. “On November 4, 1981, the concentrator started processing ore, and reached full production capacity by March 1982.”

The plant was designed with a throughput of 2,050 tonnes per day (tpd). However, G.A. Kosick, L.A. Kuehn and M. Freberg (CIM Bulletin, December 1988) recorded that, since 1986, the plant had been treating about 2,800 tpd of feed with average grades of 3% Pb, 13% Zn and 5% Fe. “Current production averages 36,000 tonnes of lead concentrate and 220,000 tonnes of zinc concentrate annually,” they wrote.

The restricted shipping season also necessitated the construction of a large A-frame building to store concentrate for shipment in the summer. “The concentrate storage building, which is the largest manmade structure in the Arctic, is designed to hold a year’s production of 220,000 tonnes,” wrote Gowans.

Geotechnical considerations

The presence of permafrost, which extended from the surface down to a maximum of 500 metres, influenced mining techniques at the Polaris mine. The orebody, which was approximately 400 metres wide by 700 metres long, was situated completely within permafrost, according to Steve Dismuke and Tom Diment (CIM Bulletin, November/December 1996); about 25 per cent of the mine’s reserves were in the upper portion of the orebody, called the Panhandle Zone, with the remainder in a larger and deeper (and therefore warmer) portion called the Keel Zone.

“The influence of permafrost on the physical characteristics of the ore cannot be overemphasized,” they wrote. “The ore contains up to 5% moisture by weight in the form of ice. In the frozen state, the ore is quite competent. If allowed to thaw however, much of the ore deteriorates to the extent that samples cannot be handled without them crumbling.”

To preserve the integrity of the rock, the thermal equilibrium of the mine had to be maintained. The initial mining method was open stoping with subsequent backfill, later followed by pillar recovery. Using conventional hydraulically placed mill tailings as backfill was considered, but Drake and Keohane (1985) wrote that “thermal analysis indicated that this would introduce an amount of heat that would significantly alter the thermal equilibrium in the mine so that thawing of pillars was likely.”

According to Dave Baril, John Knapp and Steve Douglass (Canadian Milling Practice, CIM Special Volume 49, 2000), the mine instead initially used frozen backfill consisting of quarried material mixed with 10 to 15 per cent water. “It was placed underground by free dumping down a series of 1.8m-diameter raisebore holes collared on surface,” they wrote.

According to A.J. Keen (CIM Bulletin, June 1992), significant sources of heat that threatened the permafrost included diesel engines, fresh water used for backfill consolidation and electrical power; collectively, these contributed 82 per cent of the total heat generated.

“In September 1983, two thaw-induced groundfalls caused by warm ventilating air prompted the installation of a mine air cooling system,” he wrote. “A 450-tonne refrigeration plant capable of cooling 118 m3/s was installed and commissioned for the 1984 summer.”

In December 1994, the Polaris mine began investigating the use of cemented rockfill (CRF) to supplement the frozen rockfill system. “[CRF] improves stability, maximizes ore extraction by eliminating the need for post pillars, and accelerates the development, production and backfill cycle time,” wrote Baril et al. (2000). “The frozen backfill was taking one to three years to freeze which unacceptably extended the mining cycle.”

According to Dismuke and Diment (1996), although CRF had been used successfully at several mining operations by this time, the team faced the additional challenges of making a reliable cemented product in permafrost conditions and procuring and storing one year’s supply of bulk cement (approximately 13,000 tonnes).

“In early April 1995, based on strong economics, favourable test work results and a preliminary process design, the capital to build the 3,000 tonne per day CRF plant was approved,” wrote Dismuke and Diment.

Construction of the CRF batch plant began in late September, three weeks later than planned, and was completed in February 1996.

Closure

The Polaris mine ceased operations in September 2002, which Ross L. Sherlock, David J. Scott, Gordon MacKay and Wayne Johnson (Explor. Mining Geol., Vol. 12, Nos. 1-4, 2003) attributed to “depleted reserves and low commodity prices.” They noted that the Polaris mine and two other mines in Nunavut, the Lupin gold mine and the Nanisivik mine (which also closed in fall 2002), “collectively produced 2.1% of Canada’s non-fuel mineral output in 2001.”

Over its 21 years of operations, the Polaris mine produced 20.1 million tonnes of ore at 13.4 per cent Zn and 3.6 per cent Pb.

Cominco had merged with Teck Corp. in July 2001, becoming Teck Cominco (known as Teck Resources since 2009). The company began a two-year, $55 million decommissioning and reclamation program at the Polaris mine, which was completed in September 2004.