Alberta Premier Rachel Notley announced a climate change plan on Nov. 22, which includes an annual carbon emissions cap of 100 megatonnes on oil sands operations. Chris Schwarz, Government of Alberta

The year 2015 brought new standards for mining jurisdictions around the globe. Transparency, taxation and social contributions featured prominently in the new rules put forward, especially in Africa. At the same time, encouraging mining activity remained a top priority for governments. Here is a look at the tenor of legislative changes this year.

Passed

In Burkina Faso, a new mining code required by the World Bank and demanded by the public improved oversight of the industry while increasing its contributions to state coffers and local communities. The new code, passed in June, removes a 10 per cent tax break, bringing mining companies up to the fixed corporate tax rate of 27.5 per cent. It also requires companies to contribute one per cent of revenue to a local development fund, in response to a campaign mounted by local and global NGOs. “We don’t view the new code unfavourably, with the exception that the corporate tax has increased,” said Doug Reddy, executive vice-president of business development at Endeavour Mining. “But we always found [Burkina’s mining tax rate] to be the anomaly in the region.”

In Canada, the Extractive Sector Transparency Measures Act took effect in June. It requires mining, oil and gas companies with a Canadian presence to report payments to governments of more than $100,000. The act is part of an international effort to combat corruption, and follows the recommendations of a working group that included MAC, PDAC, and Publish What You Pay.

Morocco passed a new mining code in August that expands the list of mineable minerals, allows exploration rights over larger areas and requires mining licenses to go to demonstrably qualified businesses, to ensure sites are developed. “The new mining code has aimed to remove a series of obstacles” to mining investment, according to Casablanca attorney Abdelatif Laamrani who said the code would give his mining clients confidence and enlarge investment in the mining sector.

As of February 2015, Turkey is charging more for exploration and operating licenses to discourage speculation. Another modification scales the royalty rate to commodity price; royalties can be between two and 16 per cent depending on the current price of the commodity mined.

Mining license holders in Uganda are no longer required to pay value-added tax (VAT) on invoices from contractors. Uganda also reduced withholding tax on payments to nonresident contractors to 10 per cent, down from 15 per cent. “In our view, these recent changes are a very positive gesture from the government to improve the tax environment in the extractive industries sector,” said Nicholas Kabonge, a PricewaterhouseCoopers tax consultant. “VAT in particular was a significant cost in the sector and it took a significant effort of lobbying from the sector to have these changes effected.”

Proposed

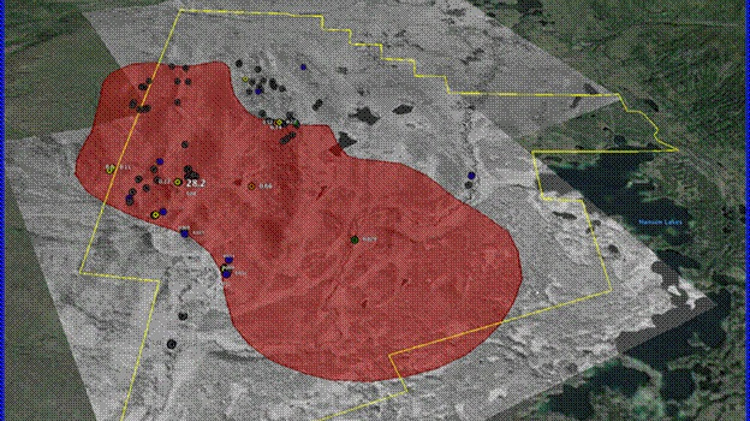

Alberta moved to rebalance the costs and benefits of its energy industries. A climate change plan released in late November includes a carbon tax on all emitters and an annual carbon emissions cap of 100 megatonnes on oil sands operations. A separate 10-megatonne cap applies to any new upgrading and cogeneration facilities. Coal-fired power plants will be phased out in favour of renewable sources. Meanwhile, an oil and gas royalty review panel will produce a report by the end of 2015 that could result in changes to any royalties paid from 2017.

Australia is expected to pass a bill before the end of the year intended to close a major tax loophole, after a senate investigation revealed multinationals, including BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, had shielded revenue generated in Australia from taxation.

The government of Senegal submitted a draft mining code to Parliament with the goal of passing it in 2015. An analysis by law firm DLA Piper suggested the revised code keeps Senegal investor-friendly while raising permitting fees and taxes, adding stronger social and environmental obligations, and setting deadlines for permitted mines to start operation, with fines imposed for not meeting them.

Up in the air

British Columbia formed a mining code review committee to determine ways to implement seven recommendations made by the Mount Polley independent review panel. Regulatory changes will be announced in 2016. Karina Briño, president and CEO of the Mining Association of British Columbia, said she expected mandatory independent tailings review boards to be one of the new regulations.

Zambia’s mine royalties seesawed in 2015. In January its six per cent royalties were raised to 20 per cent for open pit mines and eight per cent for underground mines. In April, the government retreated to a uniform nine per cent, citing poor copper prices and consultations with the mining industry. Zambia’s Chamber of Mines continues to call for a six per cent ceiling, in light of the “grave, if not perilous” state of Zambia’s mining sector.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo submitted mining code changes to Parliament in March. The draft code raises the profit tax to 35 per cent from 30 per cent. It also raises royalties on copper and cobalt, precious metals and gems between one and two per cent each. The country’s Chamber of Mines opposed the draft. Advocacy group Global Witness also criticized it for insufficient transparency rules and for removing conflict-of-interest provisions preventing politicians and army officials from owning mining rights. “The matter has been idle for a while,” said Hubert André-Dumont, a partner at McGuireWoods LLP who specializes in Congolese mining law. He suggested global metal prices and Zambia’s fluctuating royalties were possible culprits for the stalled progress, but added that there are signs the government is prepared to lower its tax hikes.

Soon after the departure of Guatemala’s president in September, the Supreme Court overturned a royalty hike passed in December 2014 that had raised royalties to 10 per cent from their previous one per cent. Ira Gostin, vice-president of investor relations at Tahoe Resources, said: “We still don’t know exactly how this will affect us but we are optimistic and hopeful that the new government will work on a new mining law with a more progressive royalty structure.”

Vietnam decreed foreign gold miners could deduct production costs before applying royalties of 15 per cent. But Vietnam is also considering higher mineral royalties as a way to balance the revenue lost from the lowered tariffs required to enter recent trade pacts like an EU free trade agreement and the Trans-Pacific Partnership, according to Oliver Massmann, general director of Duane Morris Vietnam LLC.

|

|

Asteroids like 243 Ida, pictured here, could be sites for American miners’ future exploration projects because of a new law. Courtesy NASA/JPL

|

Space: the final jurisdiction. These are the ambitions of the United States Congress, which voted in 2015 to allow U.S. citizens and corporations to keep any non-living “space resources” they acquire while operating under international law. It is still unclear exactly how the Space Act of 2015 jibes with the UN’s 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which doesn’t prohibit mining but does put celestial bodies off-limits to national appropriation. But if hopeful space miners can really claim U.S. property rights, the asteroids won’t know what hit them.