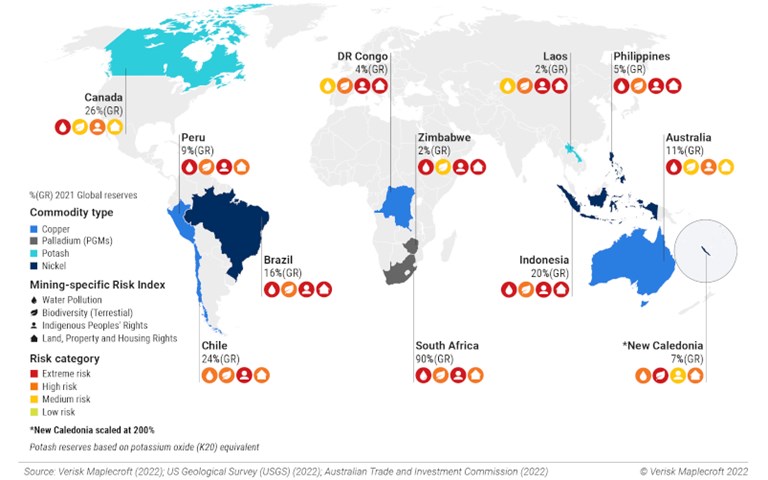

Shifts to new sources of critical miaterials will expose companies to new ESG risks. A lesser known jurisdiction like Laos or the Philippines could have the resources to help fill the gap left by Russia, but come with their own ESG risks. Courtesy of Verisk Maplecroft

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been a significant contributor to the chaos affecting metals markets over the past months, and as a result, it might be time for some mining companies to make some tough decisions.

Heavy sanctions have made operating in Russia and its ally Belarus near impossible, but demand for critical minerals needed for the green energy transition – copper, nickel and cobalt, for example – is expected to grow significantly over the next decade, and Russia is a major producer for several of them. According to a new report from Verisk Maplecroft, in order to try and bridge that supply gap, mining companies will be required to operate in lesser-known markets that can be prone to higher levels of ESG risk.

The report used Verisk Maplecroft’s Industry Risk Analytics data, which measures 51 different risks across 198 different countries, but specifically focused on four that are critical to ESG in the mining industry: water pollution, biodiversity, Indigenous Peoples’ rights, and land, property and housing rights. According to Will Nichols, head of climate and resilience at Verisk Maplecroft, those areas were chosen specifically for a future-facing mining industry.

“With our Industry Risk Analytics data, there’s a whole host of different things we could have potentially looked at, but these ones we thought were most prevalent to the coming mining industry,” Nichols said. “But ESG can encompass corruption, modern slavery and other aspects as well that could potentially impinge on operators, especially if they’re unaware of the levels of these risks in these new markets.”

For instance, Russia contains seven per cent of the world’s copper reserves and provided most copper exports to the European Union in 2020. Without that supply, operators might instead look towards countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia and Indonesia, which are characterized by the report as having high environmental and social risks compounded by high levels of corruption. As such, to avoid possible ESG risks, it is imperative that companies are aware of these risks ahead of time and try to address them.

“It’s difficult to find any major mining company that doesn’t have a code of conduct, and obviously they have investors holding their feet to the fire as well,” Nichols said. “But that doesn’t mean you don’t see ESG issues happen.”

It might be tempting for some companies to put ESG considerations to the side as they establish themselves in new markets to address the desperate need for these materials, but according to Nichols, that would be a mistake.

“I personally think that investors are taking a longer view. I think there is certainly still plenty of people who are looking quarter-to-quarter, but my experience with the clients that we speak to is that people are looking at ESG and sustainability in a kind of longer-term context,” Nichols said. “So if there is that kind of supply chain dip that is hitting profitability, if investors are convinced that a company is dealing with it in the right way and maintaining its ESG integrity, there is less of an issue. If a company was to throw off its ESG policies for short-term gain, I’m not sure many investors would be convinced by that.”

Unless new deposits in less risky markets are found, it will lead to a sort of unavoidable Catch 22 for companies looking to take advantage of the upcoming demand. While an end to Russia’s war with Ukraine might seem to the optimistic as a possible return to normalcy, according to Nichols, it’s unlikely that Russia will be a potential destination for American and European miners ever again. Rather, companies will instead have to quickly and carefully assess their risk profiles while building supply chains.

“It’s going to be difficult to return to Russia as a market. It’s a difficult question for companies, because they’ll have supply chains built there, they’ve got all sorts of infrastructure already there, so the difficulty for them is starting anew in some of these other countries, which is what we’ve mentioned in terms of building up those relationships and finding out the risks in those markets,” Nichols said. “It’s ultimately a balance. Which risk are you prepared to deal with, and which are you not prepared to deal with? I think for each company, that’s going to be a slightly different calculation.”