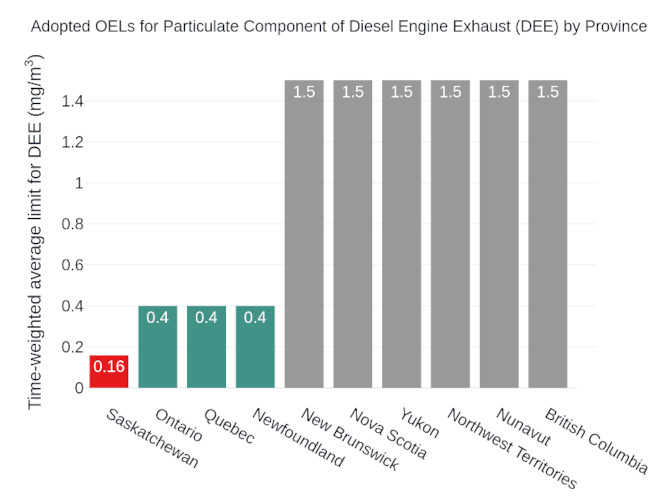

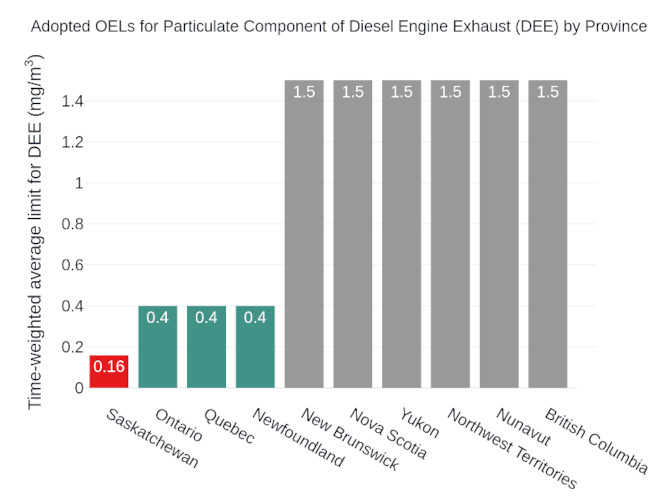

Limits on diesel engine exhaust are determined by the province and can differ in total amount permitted and measurement type.

Miners are trained for and face numerous risks while working at underground operations. Falling rocks and equipment fires are very dramatic, but one of the most common risks faced by underground miners may be one that we encounter every day: the carcinogenic particulates released from diesel-powered vehicles, summarized by industrial hygienists as diesel engine exhaust (DEE).

Mining companies take steps to mitigate their workers’ exposure to DEE through the use of powerful ventilation systems in order to operate within their jurisdiction’s set limit. In Canada, these limits are determined by the province and offer different levels of protection for different jurisdictions.

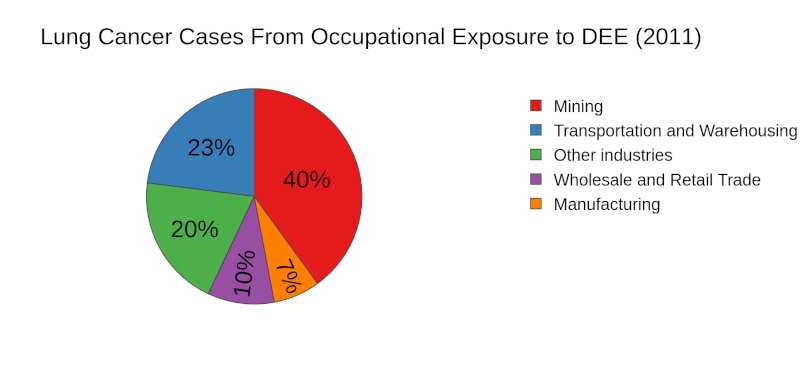

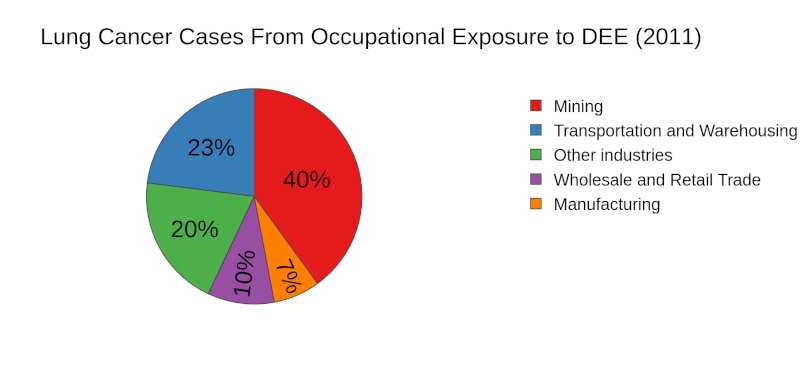

Many industries face exposure risks to DEE, transportation and construction chief among them, but high amounts of exposure bring increased risks. In June 2012, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, a part of the World Health Organization, classified DEE as carcinogenic to humans, finding sufficient evidence that DEE increases the risk of lung cancer and limited evidence of increased risk of bladder cancer.

According to the Occupational Cancer Research Centre, based on 2011 cancer statistics, approximately 560 lung cancers and 200 suspected bladder cancers in Canada are attributed to occupational exposure to DEE each year. Out of those, 220 lung cancers and 20 suspected bladder cancers are estimated to occur among those in the mining industry.

Data sourced from Occupational Cancer Research Centre.

Data sourced from Occupational Cancer Research Centre.

Those working underground are naturally exposed to the highest levels of DEE, given that they operate in closed environments with large, diesel-powered machinery. Underground mining is one of the only industries in Canada to enforce limits on carcinogen exposure stemming from diesel, but these limits are determined by the province and based on feasibility, so the limits are higher than what would normally be recommended.

As detailed in a 2019 report entitled “Setting an occupational exposure limit for diesel engine exhaust in Cananda: Challenges and opportunities” from CAREX (CARcinogen EXposure) Canada, a multi-institution team of researchers funded through the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, there is no unified occupational exposure limit (OEL) for DEE in Canada whatsoever. Instead, provinces determine their own OELs, most of which are based on the recommendations of the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH).

Although provinces take the ACHIH recommendations into consideration when setting their own guidelines, provincial regulations are based on feasibility, allowing miners to be exposed to higher limits than recommended by the ACGIH.

“The position we’ve taken at CAREX, and that a lot of other academic industrial hygienists have [taken], is that we should be trying to do better about harmonizing occupational exposure limits across the country, because the way that regulations are set in the country, its workers are differentially protected, depending on where they are,” said Cheryl Peters, principal investigator at CAREX.

Another point of confusion is the differences in substances that the OELs are measuring. ACGIH does not have an OEL specifically for DEE, rather, it has OELs for other carcinogen size fractions that encapsulate a larger source of carbons, or carbons that are not specific to lung cancer.

“The whole thing that ACGIH doesn’t have an OEL for diesel on the books is part of the problem as well, because now all the provinces are just running around trying to figure out what to do,” Peters said. “As their legislation says, they have to use ACGIH, and ACGIH doesn’t have an OEL for diesel. So, they’re trying to figure things out on their own. What can they do? What’s feasible? What’s ‘reasonably protected’ for workers? What’s going to be acceptable for employers?”

According to Peters, the adoption of the ACGIH OELs has both advantages and disadvantages. As it stands, ACGIH is the best place to source an OEL, since it is an independent body of experts who determine the limits strictly based on health, and not on industry feasibility. Some provinces have outdated versions of OELs enshrined in their legislation, rather than continuously updating them to the newest edition.

Related: Culture gaps and complacency are contributors to mining safety issues

Three provinces – Alberta, Manitoba and Prince Edward Island – have not adopted any OELs for the particulate component of DEE, though Manitoba has previsions regarding the gaseous component and Alberta has an OEL for total hydrocarbons from diesel fuel.

Most provinces have adopted an OEL based on “respirable combustible dust” at a limit of 1.5 mg/m3 based on an eight-hour time-weighted average (TWA). Other provinces measure “total carbon” at a limit of 0.4 mg/m3, with Saskatchewan having adopted a total carbon limit of 0.16 mg/m3. (Ontario has proposed an updated OEL matching Saskatchewan’s, but so far has not adopted it into law.) In the report, CAREX recommends that based on the current evidence of increased lung-cancer risk at low levels, Canadian jurisdictions should adopt an OEL of 0.02 mg/m3 of elemental carbon, which is a fraction of total carbon. According to Peters, elemental carbon is the most precise measurement for carbon associated with DEE.

“If you’re trying to characterize the risk in an underground mine, where you have other mineral dusts which can have carbon in them... You might have oil mists, which also contain carbon, and if anybody is smoking that will also have carbon. People have been trying to find something that’s very specific to the actuality of what’s coming out of the tailpipe or what’s coming out of the machinery,” Peters said. “Elemental carbon is what people have settled on as it is a pretty direct link with the risk of lung cancer… Also, if you get it at the right size fraction, then it is very specific to diesel engine exhaust.”

Other countries and even individual mining companies have adopted or exceeded nationwide OELs for matter associated with DEE. For instance, in 2006 the US Mine Safety and Health Administration set a limit of 0.16 mg/m3 over an eight-hour TWA based on total carbon. Australian-miner BHP set an OEL of 0.03 mg/m3 for its operations in 2016, which is stricter than its local regulatory requirements.

These limits also have direct implications on the designs of the mines themselves. Like OELs, ventilations systems for mines have their own province-specific regulations determining the air volume requirement based on the tier-emissions ratings of the engines of the mine’s vehicles, typically measured in m3/kWs. For example, Ontario uses a minimum ventilation standard of 0.06 m3/kW adopted by most provinces, while Quebec uses CANMET’s ventilation rates which can change depending on the engine.

Data sourced from CAREX.

According to Jose Pinedo, Ventsim sales manager at Howden, mines typically size their ventilation systems differently in order to match the OELs of their province.

“The majority of provinces use the same dilution factor when it comes to being able to comply with the amount of air required for diesel equipment… Depending on the tier of the engine, let’s say it’s a Tier 4 engine, it’s going to have lower ventilation requirements, so there’s an incentive to buy a more efficient engine, because you can lower your ventilation requirement at the mine,” Pinedo said. “For provinces like B.C. and Ontario, there are occupational exposure limits. So, for CO, which I think is 20 ppm per eight hour shift, they would be sizing based on the amount that they’re required to make sure that the CO level at the end of the shift is less than that.”

Lower exposure limits necessitate stronger ventilation to meet them or require investing in higher tier engines to save money on ventilation costs.

“Here in Quebec, mines are going to have lower ventilation requirements. You can have lower vent prescriptions for the same engines you have in one province or another, based on legislation,” Pinedo said. “Let’s say I have the same Sandvik truck, I’m going to require less air here, thus the fans are going to be smaller, thus my operating cost is going to be less.”

Mine operators also take steps to continuously monitor exposure levels in underground operations, employing the use of electronic gas sensors. Additionally, operators who have adopted popular sustainability standards such as the Mining Association of Canada’s “Towards Sustainable Mining” are required to maintain a documented industrial hygiene program reviewed by a qualified hygienist that measures workers’ exposure to multiple health hazards, including the carcinogens measured by the province’s OELs.

This is an issue that could wind up solving itself as well, given that the increasing adoption of battery electric vehicles will vastly reduce the amount of DEE workers are exposed to underground. Health Canada is also undergoing a review of how chemicals are regulated to better protect workers, which could lead to the creation of a nationwide OEL. However, it will still be up to the provinces to actually adopt them. Even so, the adoption of a nationwide OEL, based on the latest scientific evidence, would provide standard criteria that the mining industry could use to ensure that it is doing the utmost to keep employees safe.

“The mining industry knows very well that this is a problem, and I think, in a lot of cases, is trying to replace diesel producing equipment where they can,” Peters said. “I think everyone who has diesel equipment has been trying to do something to reduce exposure, knowing that it’s a legal liability, but also that they don’t want their employees to get sick from lung cancer.”