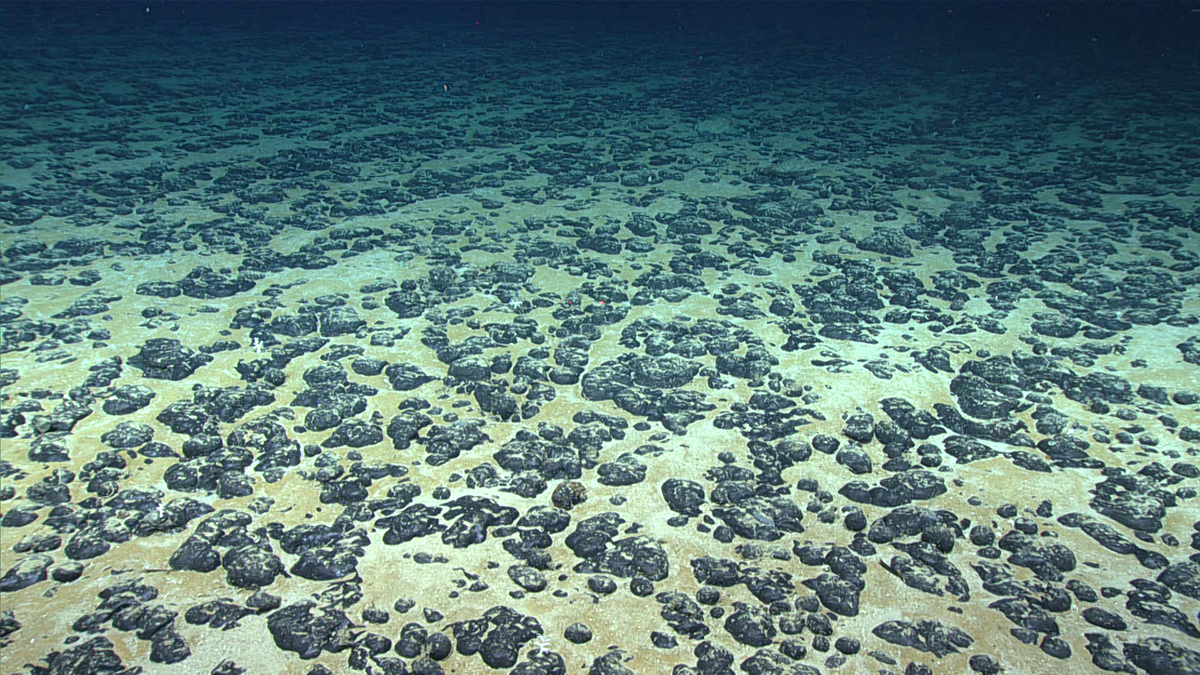

Samples of pyrrhotite-rich mine tailings collected for research at MIRARCO’s new biomining pilot facility in Sudbury, Ontario. Courtesy of MIRARCO

The Mining Innovation Rehabilitation and Applied Research Corporation (MIRARCO) has opened a new 10,000-square-foot piloting facility in Sudbury, Ontario, dedicated to applied research in bioleaching and bioprocessing.

The facility, which officially opened on Oct. 16, will focus on developing and testing various biotechnologies to recover critical minerals from both legacy and recently produced mine wastes to ensure a more sustainable mining future. Before opening this new facility, MIRARCO operated out of Laurentian University and will continue its partnership with the university.

Nadia Mykytczuk, president and CEO of MIRARCO, told CIM Magazine that this pilot facility builds on two decades of work developing new tools to help the mining industry better manage long-term mine waste legacies. Over the years, she has noticed that many scientific discoveries never progress beyond the laboratory or scientific literature, leaving a persistent gap between research and practical application.

“There are various [biomining] piloting facilities across Canada, but [only] a handful that allow that very important scale-up that is needed to refine and to derisk these types of technologies,” she said. “More and more, we’re seeing the private sector reduce their overall research and development capacity and initiative...so our [longer-term] vision is to help fill that gap and support the industry on a broader scale.”

Scaling up

Biomining has existed in various forms for several decades, but according to Mykytczuk, the enduring challenge lies in demonstrating reliable, full-scale mineral processing operations using bioleaching—a process that uses bacteria to break down mine waste to extract minerals—across a range of materials.

“Most bioleaching globally at a commercial scale has occurred either for copper through heap leaching or for gold recovery in stirred tank bioreactors,” she said.

She has observed that a key reason some bioleaching operations have failed is the inability to monitor the biocatalysts in real time, among other process control challenges. She noted that, with genomics tools, it is now possible to assess the microbial population and activity as part of process control and monitoring, adding that this is one aspect that has significantly improved the reliability and robustness of bioleaching technologies.

She explained that routine process controls, like temperature or pH, have long had instruments that measure a single parameter. Bioleaching, however, is driven by a group of microorganisms—dozens of dominant species and hundreds of low-abundance species—that exist in the bioreactors and drive the breakdown of the target minerals. This community of microbes has long been considered a “black box” because the ability to identify individual microbes lacked simple tools, like a pH probe, that could give an operator a single output.

“We now have various genomics and molecular tools that can detect the presence, absence, abundance or activity of the microbes in the bioreactors,” she said. “While these tools are still not as simple as a thermometer, researchers and tech companies are working to make them more user-friendly.”

Building on these advances, one of the initial projects being undertaken at the pilot plant—supported by a $5 million grant from Natural Resources Canada through the Critical Minerals Research, Development and Demonstration program—involves piloting and comparing several bioleaching technologies to identify the most effective and sustainable method for recovering nickel, cobalt and copper from pyrrhotite-rich tailings at mine sites in and around Sudbury.

Pyrrhotite is a highly reactive iron sulfide mineral that, when exposed to oxygen, releases soluble acidic iron that can harm the environment, making its safe treatment a priority for sustainable mining practices.

The project is being carried out in collaboration with Vale, environmental technology company BacTech Environmental and several additional partners.

“It takes a lot of different multidisciplinary researchers to tackle this [challenge],” said Mykytczuk. “MIRARCO’s role is really to scale up and pilot these technologies, help refine them and work with industry end users to see how best to modify that technology to get it to a scale that the industry could eventually adopt.”

The pilot facility will not limit its research to a single material or commodity; Mykytczuk noted that MIRARCO is “trying to use biotechnologies to develop bespoke solutions, so these are for every [type of] mine waste, for every material.”

To achieve that, the pilot facility is open to collaborating on future projects with a variety of organizations, including major mining companies, start-ups and technology firms. This could include companies interested in utilizing residual byproducts or water firms looking to test their technologies on highly concentrated effluents.

A key partnership, first announced at the opening of the pilot facility, has already been formed with Taighwenini Technical Services Corp., the economic development arm of Wahnapitae First Nation. Together, MIRARCO and Taighwenini are commercializing technologies while providing youth training programs in mineral processing, microbiology, automation, chemistry and process control. The partnership will also support demonstration projects focused on reclaiming legacy mine tailings.

By combining hands-on pilot proj-ects with collaborative partnerships, MIRARCO is advancing technology development while also laying the groundwork to strengthen Canada’s overall critical minerals capacity.

“It really takes a village to build all of the nodes across the critical mineral supply chain,” Mykytczuk said. “We recognize that for all the mines we need to build, and all the materials we need to process, research and development and these scale-up facilities are important. We do not have a lot of them in Canada, so this is something that we are committed to growing, and we hope that we can partner with other institutions to help build out that capacity.”

Future plans

Mykytczuk explained that the new piloting facility is part of a broader plan to establish a Centre for Mine Waste Biotechnology (CMWB). This centre will be a permanent research hub where various biotechnologies can be scaled, derisked and adapted into commercial biomining solutions for reprocessing tailings and mine waste.

Once completed, the proposed centre will enable MIRARCO to expand its capacity, create new training opportunities for students and scale various components of biotechnologies in collaboration with different industry partners. MIRARCO has already spent seven years developing the vision and model for this centre, with detailed engineering designs for a 48,000-square-foot facility now complete.

“MIRARCO continues to work on development plans for construction of the full CMWB,” Mykytczuk said. “We hope that we can secure all capital funding soon and break ground in 2026 or 2027.”