Part six of a series on NI 43-101 myths

Old mineral projects that didn’t make it before are often dusted off, given new wings and told to fly again. That’s not necessarily a bad thing—better technologies and changing economics can sometimes elevate a project awaiting its chance. And a project with a past could be seen to have a head start based on previous work.

When a company has a project with previous work or previous mineral inventories, that history will often be material information the company should include in its technical disclosure. Accurate and complete disclosure of historical information gives investors a good idea of what kind of work a project may need; that five other juniors poked some holes in the property and cut a few interesting intersections could mean the property has potential or could just mean it’s been a five-time disappointment.

If there are historical estimates—and the estimates still have some relevance to the project today—then those numbers will help the public understand a project’s potential.

If you’ve been following this series of columns, you’ll know we always pull out the “damning but.” This time, it’s to say "but historical information is not your work." You did not control it, and you don’t know for sure how good it is. That is why National Instrument 43-101 provides a way to let the public see the information without forcing the company to file a technical report. But that also means the need for handling the information responsibly. Historical information requires a source and date, an opinion on its relevance and reliability, and context.

Historical estimates

Historical estimates can be anything from a detailed data set transferred to a new project operator to a simple record of an old tonnage and grade calculation in an assessment file. Solid information about that “relevance and reliability” that the Instrument requires you to comment on is easy to come by in the first case, and a closed book in the other. It is important to assess whether that closed-book estimate brings any value at all to an investment decision—and it certainly won’t if you can’t trace it to its origin.

The fact is that a long list of old estimates does little more than tell the public there’s some mineralization there—quantifying that may not help much.

It is worth noting that a historical estimate—whatever label a previous operator might have stuck on it—is no longer a mineral resource or mineral reserve, even though the mineralization might still be there. Loose talk about having “a mineral reserve from 1962” or “an NI 43-101 compliant mineral resource by a previous operator” is nonsense. Why?

Because it’s only a resource or reserve once it meets the CIM definitions, and it’s only a current mineral resource or reserve once the company discloses its own estimate (and starts the clock on filing its own technical report).

We should also draw a distinction between historical estimates and legacy data. Having legacy data can permit you to go back and verify it through resampling core, twinning holes or infill drilling. Having old estimates, but no access to core or data, means only that you can tell the public an old operator thought it had a mineral deposit, but the new operator has to verify this for itself.

History in technical reports

Once a company is ready to file its own technical report on the property, it becomes important to remember that Item 6 on Form 43-101F1, the “History” section, is intended only to be a summary and not an exhaustive documentation of everything that has been done since Georgius Agricola swung his pick. Chances are most of that history is not material.

The History section gets even worse when it is used to shoehorn an in-depth account of the previous operator’s resource estimates, which directly contradicts the cautionary language that is supposed to accompany it—especially the part that says you’re “not treating the historical estimate as current mineral resources or mineral reserves.” What you are actually saying is “Look at the exquisite work that last operator did. Look at its quality control, its semivariograms and its swath plots, aren’t they pretty? We’re immensely confident in their mineral resource estimate, as you should be too. We’re just not putting our names on the estimate ourselves.”

Old economic studies by others are not historical estimates so the allowance for disclosure with caution does not apply.

In the 2003 movie Big Fish, Albert Finney plays a character whose fondness for historical accounts of his fantastical past complicates his relationships with others who try to separate fact from fiction. You can avoid complications by always keeping project histories simple and limiting them to their genuinely important and relevant parts. While Albert Finney’s character continued on, your mineral project may not.

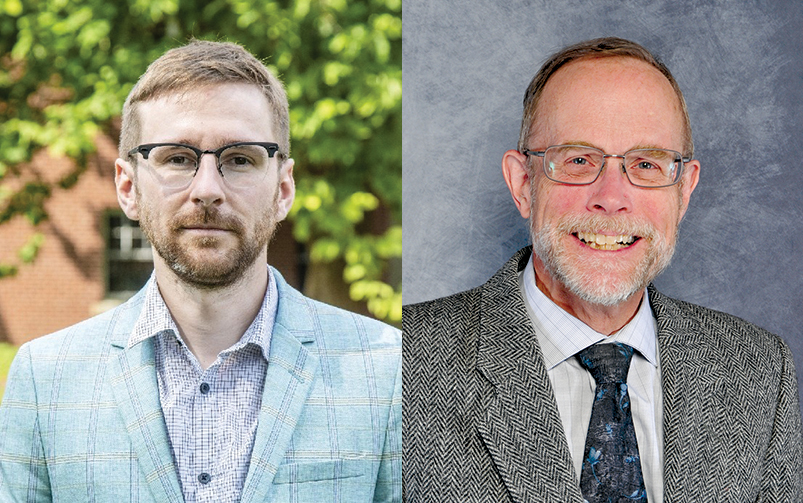

James Whyte, P.Geo., retired in 2023 from his role as senior geologist at the Ontario Securities Commission. Craig Waldie is a senior geologist at the Ontario Securities Commission. Both authors are writing in their private capacity.