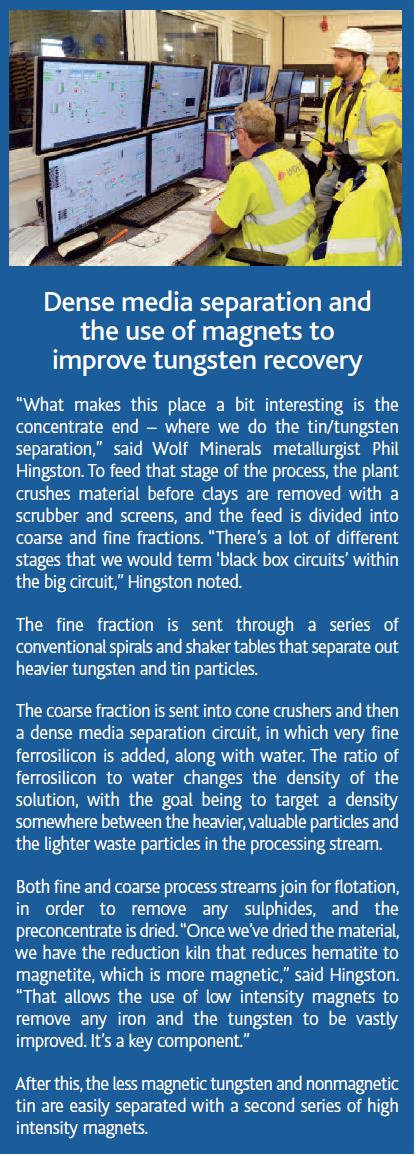

The Drakelands mine is 11 kilometres northeast of Plymouth in southwest England. Courtesy of Wolf Minerals

Negotiations were not always easy for Jeff Harrison when, five years ago, he went knocking on doors near the village of Hemerdon, United Kingdom, to convince people to sell their homes. His pitch: with their cooperation, the region would see some 220 new jobs, injecting badly needed cash into the local economy. All that hinged on the startup of the Drakelands tungsten mine, which had been in the works in some form or another since 1867.

Ultimately, the 15 owners accepted the offer. “Some of them still come back and visit the site to see where their houses used to be and see how the mine developed,” said Harrison, the U.K. operations manager for Wolf Minerals, whose Drakelands project is now ramping up the first new metal mine in the United Kingdom in 45 years.

The operation, which is scheduled to produce up to 5,000 tonnes of tungsten concentrate and 1,000 tonnes of tin concentrate a year, is a boon for the economy of Devon county as well as neighbouring Cornwall, where mining has traditionally been a major source of income. “There’s a lot of people in the local area who, if they haven’t been involved personally in mining, their dads were or their granddads were, so there is that family tradition,” Harrison said. “Fundamentally all I’ve seen in my lifetime is the closure of the tin industry, the demise of the coal industry and the demise of the china clay industry. There’s been nothing new, nothing positive.”

UK operations manager Jeffery Harrison. Courtesy of Wolf Minerals

Harrison has had a very personal investment in the project, and mining in the Southwest in general. “I’ve been down here since 1983, my children were born down here,” he said, recalling the 20 years he spent at a nearby china clay mine, where he was area manager, but where operations have since been scaled down. He left for Australia in 2005 to work for QMAG in Queensland, but returned to Devon in 2010. “I didn’t have a job, and it’s 12 miles from my back yard, so they couldn’t have written the script better for me.”

But reviving the United Kingdom’s metal mining industry is a big job for one man. When he joined the company five years ago, Drakelands was far from being a certain success. “When I got involved with Wolf, there were three guys in Australia and me here in the U.K. and that was it,” Harrison recalled. “Back in 2010, some people thought we were crazy and hardly anyone thought it was really going to happen.” The next year, however, the company released a positive feasibility study at a time when the price of tungsten was about US$45,000 per tonne and the project gathered momentum.

As the project ramps up to capacity in early 2016, almost every day can feel like a major milestone in British mining history. The day I visited in late October, Orica was performing the first trial blast, albeit a small one. “It’s more a few pops creating shockwaves which we can measure, and then you can start to model and design the future blasts,” said Harrison, adding that blasting will become necessary as the open pit gets deeper and the rock harder. Optimizing the blasts will help avoid unnecessary noise, dust and vibration that could disturb neighbours.

For Harrison and his crew, getting it right is very important. “As a British mining engineer, one also wants to do the right thing for the British mining industry,” he said. “When I went to university back in the 1970s, I think there were eight or nine mining colleges and we used to send mining engineers all around the world. There’s only the Camborne School of Mines left now.”

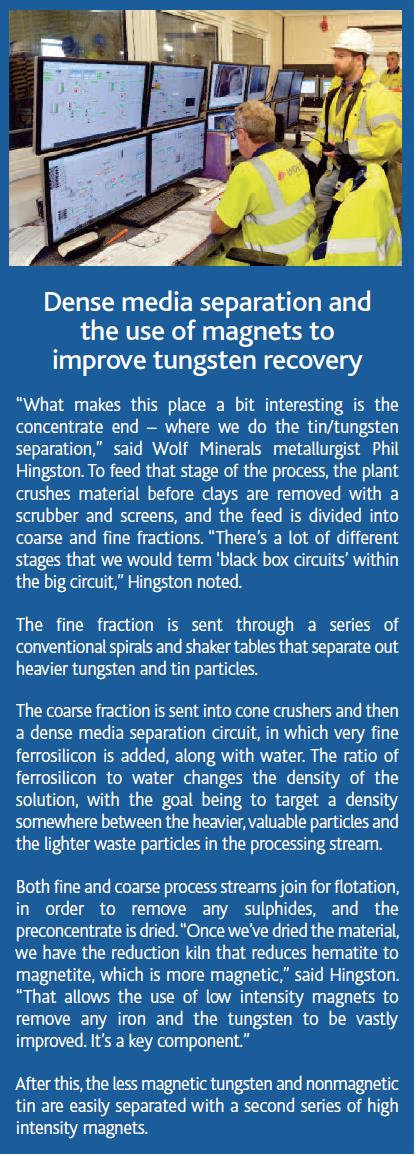

At full capacity, the mine will produce 5,000 tonnes of tungsten concentrate annually. Courtesy of Wolf Minerals

The Cambourne School

At last count, there were 14 graduates of the Camborne School of Mines, which is near Falmouth, just over 100 kilometres away, working on the Drakelands project. “It’s because we’re the best,” joked James McFarlane, a graduate of the school and a senior mine geologist at Wolf Minerals. Since he began working for the company earlier this year, he has been trying to package all of the geological data that has been collected over the history of the mine. “In order to know where you’re going, you’ve got to know where you’ve been, so I’ve built up quite an appreciation of the work that’s been done previously,” he added.

Some maps, notes and diagrams date back to the First World War, but, said McFarlane, “the majority of information comes from the work conducted from the late 1970s through to the mid-1980s. This work was conducted to a high standard but was in paper format.” Beyond digitizing the information, they have standardized it to create a more robust database for the production phase.

Part of the work that contributes significantly to McFarlane’s understanding is that of the Camborne School’s Robin Shail, whose research is focused on the geology of the southwest of England. Shail’s graduate students often undertake projects specifically examining the geology around the Drakelands deposit, where the granite that houses valuable veins of wolframite has been pushed up into the surrounding Devonian sediments that make up the region. “These are from the Devonian era, which takes its name from the county of Devon,” McFarlane pointed out. “I came into this project just thinking ‘it is what it is,’ but you get here and you look at it and you start to appreciate what a monster this deposit is. There are so many things you could do, I’ve had to reel my neck in, as the Australians would say, to make sure the critical startup and commissioning phase is spot on.”

The relationship between the school and the mine is symbiotic. “We’re happy to have one position on each of the four shifts for a graduate, rather than having them struggle to find work in any way related to their qualifications,” said Harrison. These graduates benefit from experience working in a mine and will be more employable when the industry picks up. It also enables Wolf Minerals to build a pool of young talent with the potential to fill positions as older staff members retire.

Phil Hingston, a senior plant metallurgist, is another graduate of the Camborne School and a Plymouth native. He is one of many of the team with international experience, and recalls that before joining Wolf Minerals earlier this year, he already knew or had worked with many of the tungsten-focused team. When working in Northern Ireland at a gold mine, for example, he met McFarlane. “I spent probably 15 months working with him, and we’ve always stayed in touch.”

History very present

As with most of the United Kingdom, war has left a huge impact on the Southwest. Plymouth, just 10 kilometres away, is said to have been one of the most heavily bombed English cities during the Second World War, as it is home to a major naval dockyard and army installations. But the mine, too, is in a way a product of the war.

The discovery of tungsten at the site dates back to 1867, but exploitation came much later. Processing plants were built in both the First and Second World Wars to replace the supply that could no longer come from oversees. Sadly, both of these plants barely saw any ore, as it took so long to develop the mine that by the time they could be commissioned, the wars that made them important ended and the mine was again put on hold.

But even after the Second World War, there was continuous interest in developing the project. Amax became attracted to the deposit in the late 1970s and began exploration drilling that would define much of the deposit that is under production today. Devon County Council granted planning permission to build the mine in 1986, but again the stars did not align and the price of tungsten, having crashed in the early 1980s, did not recover. Amax eventually left the land back to the landowners whose properties covered the deposit, though their planning permission extended to 2021. Thankfully for Wolf Minerals, those same permissions are still in place and work is ongoing to further extend the life of mine.

Cozy surroundings

With its dense population, England may seem like an unlikely place for mining in the 21st century. But hourly labour in the United Kingdom is actually less costly than the European average, and a generally positive attitude towards mining makes the jurisdiction attractive. Regulations, however, are stringent and can be difficult to navigate. Harrison is quick to point out that the Drakelands mine waste facility will be the first in the United Kingdom to be permitted under the new European mine waste legislation adopted in 2009. “We say it’s an environmental project, rather than a mining project,” he added. “The environmental permits through the Environment Agency have required a lot of hard work but we have worked well with the regulators on what was a first for them as well as us.”

One major benefit of this operation, though, is that the processing circuit is almost entirely gravity-based. The area does have some arsenic associated with the granite, but the company is monitoring that and working within strict conditions to prevent its operations concentrating or increasing the levels already naturally present in the region’s soils and waterways.

Ultimately, in an area where mining has been the norm rather than the exception, Wolf Minerals is a welcome neighbour bringing prosperity rather than being an adversary. “To be able to say you’ll produce four per cent of the world’s tungsten here, just six miles north of Plymouth, is quite special,” said Harrison.