A counting of tailings in CanadaLittle is known about the hundreds of tailings facilities in Canada. Our interactive database aims to shed some light on the scope of these dams.

To see a larger version of the map, click here.

Aug. 4 marked the six-year anniversary of the Mount Polley dam disaster in British Columbia, where a tailings dam at Imperial Metals’ subsidiary Mount Polley Mining Corporations titular copper-gold mine failed, spilling an approximately 25 million cubic metres of liquid tailings into the surrounding environment, including nearby lakes and rivers. Remediation in the areas affected by the breach has been ongoing ever since, and no criminal charges were ever filed against the company.

On Jan. 25, 2019, a tailings dam at Vale’s Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine in Minas Gerais, Brazil, failed, releasing 12 million cubic metres of tailings and killing 259 people with 11 still missing and presumed dead. Several senior managers at Vale were arrested, alongside two engineers from German company TÜV Süd who were responsible for inspecting the dam.

Following the disaster in Brazil, the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Council on Mining and Metals and the Principles for Responsible Investment created an initiative known as the Global Tailings Review (GTR) to evaluate current practices on tailings in the mining industry globally.

Complementing the GTR, in April 2019 the Church of England made a call for resource extraction companies to disclose information on their tailings storage facilities (TSF). Of the total 727 companies asked for disclosure, 338, or 53 per cent, did not respond. As of Feb. 26, 2020, 43 per cent of the publicly listed mining companies asked, including 45 of the top 50 mining companies, have responded, publishing their disclosures online.

This survey represents one of the largest collected datasets of tailings facilities across the world. Out of the companies that responded to the survey, CIM Magazine found 20 that have tailings facilities in Canada, representing 230 facilities in all, both active and inactive. Public disclosure from companies operating in British Columbia also identified 14 facilities from 10 companies outside the survey.

As part of an effort to raise awareness of these facilities located in Canada, CIM Magazine has created an interactive, infographic project from the data collected from the survey and publicly available government data sets. As well, the location of each known tailings facility in Canada has been marked on a searchable map, colour-coded by risk to people and the environment, with information about each individual TSF available to access.

Additionally, an open data set from the Ontario government identifies another 250 tailings facilities under control of the government in the province. All-combined, this adds up to almost 500 tailings facilities in Canada, and this likely only represents a fraction of the total amount in the country.

How the map works

If you look at the map, you’ll notice different symbols. Each symbol type – coloured circles, blue diamonds and water droplet symbols – represents a tailings facility located in Canada. For the purpose of this visualization, tailings storage facilities catalogued by the GTR and gathered from public B.C. documents are represented by the circles, abandoned facilities are the blue diamonds and oil sands tailings facilities are the droplets.

The information presented in the different data sets vary, as each company was required to provide different information depending on which datasets their TSFs would appear in. For instance, the abandoned TSFs are missing information such as construction year and risk level, while the GTR survey TSFs generally provided more thorough information.

Each point on the map is interactive and clickable. Doing so will open up a tab that provides specific information on that tailings facility. The information presented in the map is defined as such:

Company: The current corporation that owns or operates the tailings storage facility.

Name: The name of the specific facility. Some facilities can contain multiple dams.

Operation: The name of the mining operation that provides the waste to fill the tailings pond.

Latitude & Longitude: The geographic coordinates of the TSF.

Risk: The potential risk to people and the environment in the event of a dam failure. Most companies use the risk classification set by the Canadian Dam Association (CDA), though some companies such as Agnico Eagle use a similar, yet proprietary classification system. Due to the significant damage that a dam failure from a high risk TSF could cause, the GTR facilities have been colour-coded by risk. Click on the double arrow in the top-left corner of the map for an explanation of the risks each colour represents.

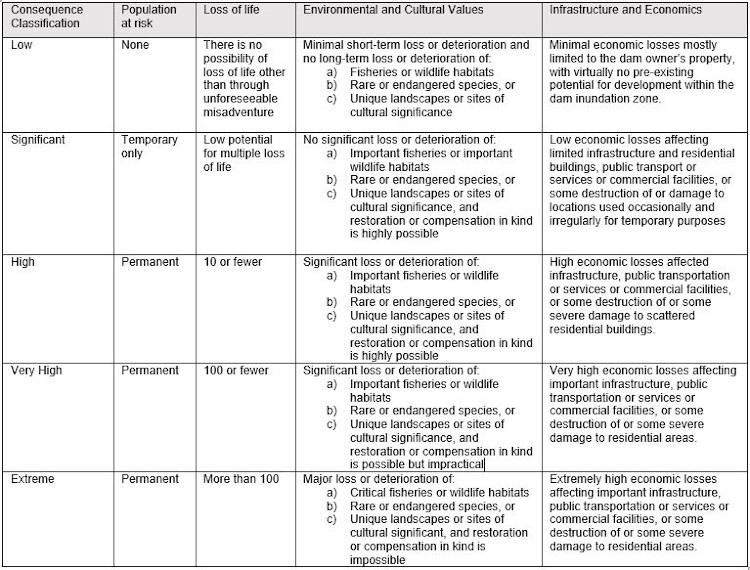

The CDA risk classifications go from low to extreme and are defined as:

Our visualization categorizes the TSFs by their consequence/risk classification, as that best displays the potential impacts tailings facilities can have on their surrounding environments. By our count, there are at least 21 facilities in Canada that qualify as having “Extreme” risk, which could cause significant damage to property and the environment, as well as loss of life.

Raising method: The type of construction that the TSF uses is known as the raising method. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages, and some TSFs can contain separate dams that use different raising methods. The most common raising methods are as follows:

Upstream: Upstream dams begin with a single dam filled with tailings. Once the contents of the dam are compacted or controlled, they can be used as a foundation for further levels of the dam as more tailings are deposited. Its design resembles a downwards staircase. Considered the least secure but least expensive method. Their use was recently banned in Brazil.

Centreline: In centreline construction, subsequent dams are built directly on top of the starter dam to raise the facility. It does not use compacted tailings for foundation support like the upstream dam does. This method lies at the centre of both risk and price.

Downstream: Downstream dams are built on top of each other similar to a centerline dam, but the walls of the dam raises create an upward slope, allowing for more tailings to be deposited in each subsequent level, opposite to an upstream construction. This method is considered the safest, yet costliest method.

Single Stage: A single stage dam is a single stage without any further additions. It’s most commonly used for smaller facilities.

In our count of tailings facilities, there is an approximately even distribution between centreline, upstream and downstream construction.

Province: The Canadian province where the TSF is located.

Active: The current active status of the TSF. A constructed TSF is considered “Active” if waste is still actively being deposited into it, “Inactive” if there’s no more waste being added and “Closed” if remediation and care and maintenance efforts have begun on the facility.

Year of Construction: The year the TSF construction was completed.

Most Recent Review: The year of the facility’s most recent safety review. Different provinces have different regulations regarding the frequency of safety reviews required. In B.C., tailings facilities must undergo annual safety inspections and be reviewed by an independent professional engineer every five years. In Ontario, the TSFs must undergo yearly safety inspections, but independent reviews are required only every 10 years, and only for TSFs with hazard classifications of “High” and “Very High.”

Notes: Specific information on the TSF provided by the company or present in the dataset.

We invite you to learn more about tailings management and construction with resources from CIM Academy, CIM Journal and our library of technical papers.

Resources

CIM Academy Webinars:

Tailings Failure Case Studies, Statistics and Failure Modes by Chad LePoudre

What About too Much Water? - Lessons Learned in Extreme Environments by Hafeez Baba

Update of a Risk-Based Approach for Mine Waste and Water Management Infrastructures by Edouard Masengo

Mine Waste Management – Tailings by Scott Holder

Canadian Mines Database Update by Donna Beneteau

An Integrated Approach to Tailings Management in the Mine Scheduling Process by Dustin Meisburger

Evaluating Passive Treatment Technologies at Mount Polley Mine for Nitrate, Selenium and Sulphate Removal from Mining Influenced Water by Sanjana Akella

Making Tailings Coarse Again - Mining Technologies that Coarsen the Size and Reduce the Quantity of Tailings by Brent Hilscher

CIM Journal

Tailings dam closure scenarios, risk communication, monitoring, and surveillance in Alberta by H.L. Schafer, R. Macciotta & N. A. Beier