The Nacho Nyak Dun, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and Vuntut Gwitchin First Nations have traditional territory in the 68,000-square-kilometre Peel Watershed, pictured, which is located in the northwest part of the Yukon. Peter Mather/Protect the Peel

The Supreme Court of Canada allowed, in part, the appeal of three Indigenous groups and two conservation groups from the Yukon looking to protect the Peel Watershed from development.

In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court justices agreed with the Nacho Nyak Dun, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and Vuntut Gwitchin First Nations and the Yukon Chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society and the Yukon Conservation Society that the Yukon government did not have authority under the agreed terms of the Peel Watershed land use plans to make sweeping changes to it in 2012.

Those changes, which First Nations strongly objected to, left 71 per cent of the watershed open for mineral exploration and the remaining 29 per cent protected. The original plan from late 2009 left 20 per cent of the watershed for mineral development and 80 per cent protected. The watershed covers 68,000 square kilometres – about 14 per cent of Yukon – in the northeast of the territory. There are about 9,000 mineral claims in the Peel Watershed region. The territorial government has estimated that $47 million has been spent on exploration there since 2002.

While the territorial government was authorized to make minor or partial changes, Canada’s top court found that what it aimed to do “(changed) the final recommended plan so significantly as to effectively reject it.”

|

|

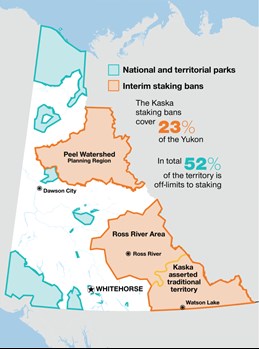

Beyond the Peel decision, mineral exploration has also been frustrated by two staking bans in the Yukon’s southeast that were put in place in 2013. Map courtesy of Yukon Energy, Mines and Resources, modified by CIM Magazine.

|

In upholding a previous trial judge’s order, the Supreme Court nullified Yukon’s approval of the plan. Both parties will return to the stage of the land use plan approval process where the territorial government can approve, modify or reject the final recommended plan as it applies to non-settlement land after consultation with First Nations. The Supreme Court set aside the trial judge’s order to return instead to an earlier stage of consultation.

Related: While First Nations and territorial government negotiate, more than half of Yukon off-limits to prospectors

The Nacho Nyak Dun, Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and Vuntut Gwitchin First Nations have traditional territory in the watershed. The land use planning process for the watershed began in 2004.

The Yukon Chamber of Mines responded to the decision stating it is “concerned with the trajectory of land withdrawals in Yukon.”

Beyond the Peel decision, mineral exploration has also been frustrated by two staking bans in the Yukon’s southeast that were put in place in 2013 after an appeal court ruled the territorial government must consult with First Nations before granting mineral rights on Crown land.

In the Chamber of Mines’ statement, Samson Hartland, the chamber’s executive director said “successful land use plans are transparent, inclusive, holistic, flexible, adequately resourced and evidence based by including socio-economic data such as mineral and exploration potential. Land withdrawals are not always being made based on sound evidence, at the conclusion of a robust policy process.”

With files from Kate Sheridan