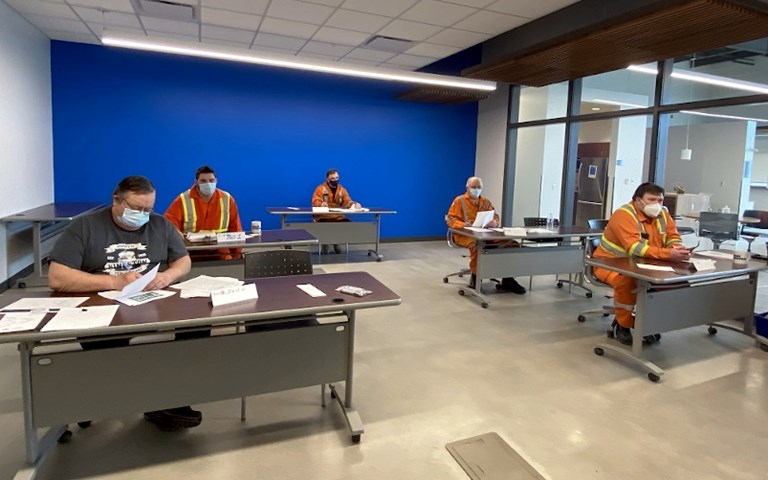

NORCAT trainers receive instruction in mental health awareness. Courtesy of Workplace Safety North

Most adults will spend the majority of of their days, and ultimately a large portion of their life, at work. Besides the income and benefits that they receive from employment, the workplace can be a place where individuals gain the sense of purpose, self-respect and motivation that help them feel like valuable contributors to society and help them lead a meaningful and happy life.

But the stresses of work can also take a serious negative toll on our inner life. The Mental Health Commission of Canada reports that “70 per cent of Canadian employees are concerned about the psychological health and safety of their workplace, and 14 per cent don’t think theirs is healthy or safe at all.” The Canadian Office for Occupational Health and Safety recommends that all employers include mental health as a key item in their workplace safety mandates, and that they review policies in order to promote mental health awareness in the workplace.

For the mining industry in particular, mental health should be a major concern for employees and employers alike. Mines can be a tough environment to work in, and employees at fly-in fly-out operations may feel especially isolated during their lengthy shifts. The Vale Mining Mental Health study, a survey of Vale workers at their operations in Sudbury and Colborne, found that of the 2,224 respondents, 41 per cent reported feeling at least mild depression, and that 10.5 per cent of respondents should be screened for post-traumatic stress disorder. Most disturbingly, the report found that “10.6 per cent of respondents indicated that they have thoughts of suicide but would not carry them out,” suggesting that mental health ought to be on everyone’s radar.

In light of the results of this study, Workplace Safety North (WSN), an organization that provides health and safety training and consulting, and NORCAT, a centre that develops skilled labour training and provides health and safety management, announced in May that they would be teaming up for a new mental health education initiative, focused on increasing awareness on the topic at mining sites.

“Our intention with this partnership is to increase the reach on this important topic, and promote why mental health matters. Ultimately, we want to help individuals that are, or know someone, dealing with mental health issues," said Mike Parent, vice-president of prevention services at WSN. To do this, Parent continued, “WSN will be providing instructor training and materials to select NORCAT trainers for the WSN mental health awareness session, so that they will be able to offer this module for [their] common core courses.”

Related: Aside from a happy workplace, there are tangible benefits of striving for employee engagement

In an interview, Angele Poitras, one of two psychological health and safety advisors at WSN certified with the Canadian Association for Mental Health, helped fill in some of the specifics on the content of the curriculum. “For the first three hours, we go through an overview of what mental health in the workplace looks like, to make the trainers comfortable with the content. These are trainers typically on heavy equipment, explosives, mining as a profession [and] their background in mental health may be little to none. The goal is to have everyone looking to speak the same language: they don’t graduate from this program as psychiatrists or psychologists, we are trainers, just as we train for underground work – this is work from the neck up.”

Poitras emphasized how increasing awareness of mental health issues could help individuals at work sites feel more secure coming forward about mental health issues, which can help to decrease the secondary physical risks that can come from working in the potentially dangerous environment of a mining site. “We know from the limited studies that are out there that when our mental health is not top of game, we’re not top of game in our industry either. That can lead to increased incidents, increased occupational stresses and it can even lead to death. So if you’re under undue hardship and suffering a mental health challenge or if you’ve been diagnosed with a mental health illness, we want you to feel safe enough to go to your employer and say ‘I shouldn’t be doing that particular job today, maybe I need to do something that has less danger attached to it or where I might not hurt myself or someone else.’” One of the major recommendations of the Canadian Centre for Workplace Health and Safety is for employers to create a space in which employees feel comfortable coming forward in this manner. Employers should fulfill their requirement to protect the mental health of their employees by “provid[ing] education and training that ensures managers and employees know how to recognize hazards such as harassment, bullying and psychologically unhealthy work conditions.” As well, employers should provide “ways to recognize and talk about mental health issues in general.”

Poitras noted how important developing a common language could be to instilling the confidence necessary for workers to come forward. “What we’ve seen in our [WSN] programs is that when we ask trainers to tell us what word or image comes into their mind when they think of mental health, we typically get words like ‘crazy,’ or ‘lunatic,’ – very negative words. Then we spend anywhere from 15 minutes to three hours with them, and I’d say probably 90 per cent of the time we see a shift in language. We hear ‘hope,’ ‘kindness,’ ‘listening,’ and in only a short period of time there is a huge shift in language surrounding mental health. Imagine what could happen over a day, a week, a month or a year. So we know it’s possible to change the culture around mental health, and it’s usually one conversation at a time.”