A series of electric-powered drive stations, such as the one shown here, propel trains filled with ore up from the Goldex Deep 1 deposit to a transfer station where it is then hoisted to the surface. Courtesy of Agnico Eagle

This was one of our favourite stories of the year. To see the full list, check out our Editors' Picks of 2018.

“Now here comes the best part. The dump loop,” said David Paquette, the general supervisor of maintenance at the Goldex mine just outside Val-d’Or, Quebec. Standing at the terminus point of its Rail-Veyor, a light rail electrically powered ore haulage system, Paquette gestured to a 360-degree loop of rail track. The Rail-Veyor, after travelling along a three-kilometre track from the lowest part of Goldex, unloads the ore it is carrying on the loop. “It’s like La Ronde.”

The description is quite apt – the dump loop looks like an industrial version of the loop de loop of a roller coaster at the Montreal theme park. Except that the ride at La Ronde does not unceremoniously drop its passengers out of the vehicle while they are suspended upside down three-quarters of a kilometre underground.

The Rail-Veyor has been hauling ore at Goldex since September last year, and is the first full-scale underground deployment of the technology in North America. The technology was installed to bring ore from the mine’s Deep 1 deposit closer to surface – and without it the deposit would not have been economically viable to mine, due to its grade (currently 1.59 grams per tonne) and location. Deep 1 has added seven years to Goldex’s mine life, extending it to 2025.

“Because we have a low-grade deposit here, we have to have a high throughput,” said Christian Lessard, Goldex’s maintenance superintendent. “You can have high production with the hoist and the Rail-Veyor.” The goal at Goldex is to keep site costs below $40 per tonne mined.

Since its commissioning, the Rail-Veyor has, as of June, hauled a total of 439,755 tonnes of ore from Deep 1, at a rate of 2,400 tonnes per day. The mine is currently ramping up to the Rail-Veyor’s total capacity of 6,000 tonnes per day, which they hope to reach by 2019, Paquette said.

Down at the 115 level of Deep 1, more than a kilometre underground, ore gets dumped into a grizzly, and a rock-breaking room handles oversize rocks. A vibrating feeder deposits material into one of the Rail-Veyor rail cars. From there, the remote-controlled train follows a circuitous track up an incline with a 17 per cent grade, from its starting point at the 1,250-metre level up to the 730-metre level. Along the way it is pushed forward by foam-filled tires at 91 drive stations that are spaced evenly along the track. The tires propel the Rail-Veyor forward by turning against the side plates of the rail cars. Loaded trains travel up to the unload point at three metres per second and, once emptied, descend at 3.5 m/s.

To prevent rocks from sliding off the lead rail car and falling on the track, loading begins at the second car.

When it reaches the dump loop, the train cruises over the top and, as it turns upside down, drops the ore into a silo. From there, the emptied Rail-Veyor returns to the starting point, and the ore is hoisted to the surface.

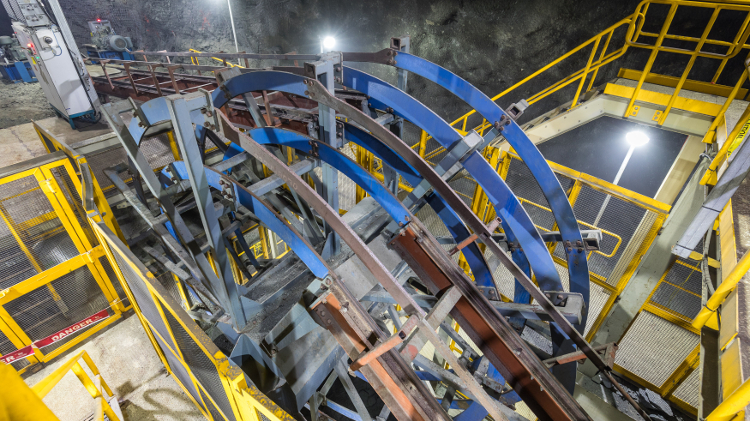

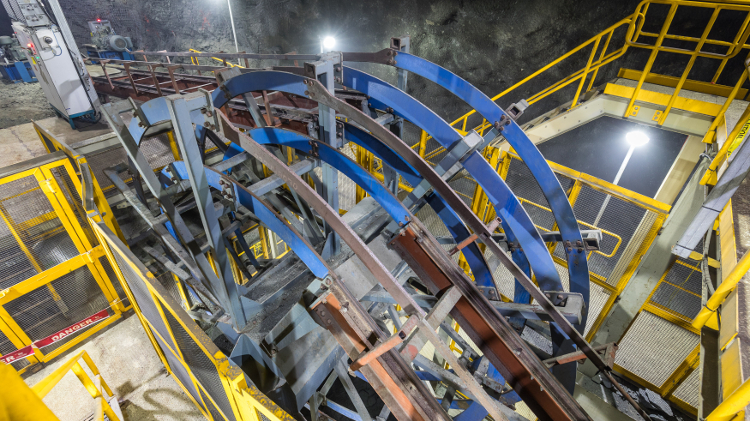

The train rolls through a loop in the track to empty its load. Courtesy of Agnico Eagle.

The train rolls through a loop in the track to empty its load. Courtesy of Agnico Eagle.

The road to Deep 1

The mineralization that became the Deep 1 zone was discovered in 2007, located underneath the Goldex Extension Zone (GEZ) that Agnico was mining, and the company commenced drilling work to determine what it had.

However, before releasing a resource estimate for the Deep zone, Agnico closed Goldex three years after it opened, due to poor rock stability above the GEZ, and above where work on the Deep zone was taking place. But a little less than a year later, in July 2012, the company approved development of the M and E satellite zones at Goldex, where rock was more stable, and reopened the mine in 2013. The GEZ has been written off completely as too dangerous to mine.

As work resumed at Goldex, the team started looking to develop Deep 1, which was greenlit by Agnico in July 2015 and began commercial production last August. They needed to extend the existing hoisting system from the GEZ to haul ore from the lower deposit, and considered multiple options, including the Rail-Veyor.

“The key for [the Goldex team] was to see if we could reduce their costs and, at the same time, extend the mine life by being able to go deeper without adding additional ventilation,” said Frank Ward, the vice-president of sales and marketing at Rail Veyor Technologies Global, the Sudbury, Ontario-based company behind the Rail-Veyor.

The team found that the technology would be cheaper to operate than haul trucks and would not require additional ventilation. It could also be constructed around curves to avoid areas of unstable ground, unlike a conveyor. “We experienced geotechnical issues in the past when we started operating in the GEZ,” Lessard said, “So it’s a priority here at Goldex to put the excavation in the best available rock.”

Related: New ideas in material handling have the potential to cut operation costs

The technology, Lessard noted, also had the added benefit of allowing the team to reuse existing exploration drifts. “We were able to use those excavations with the Rail-Veyor, so we saved a lot in terms of development costs,” Lessard said. About a quarter of the system was installed along existing 4.5 metre-wide drifts, which the company widened to 5.8 metres to allow a tractor to drive alongside the rail line. “You could use a Rail-Veyor in a smaller ramp, but in terms of maintenance and availability, we opted for a wider ramp,” he added.

And with barriers around the drifts and access control to prevent harm to workers, Lessard said the Rail-Veyor also has safety benefits. The system automatically shuts down if workers pass the barrier. It also produces zero emissions. “There’s no heat and dust coming from diesel,” Lessard said. “It’s a health and safety advantage.”

Perhaps the biggest boon is that the Rail-Veyor is able to handle larger rocks than a conveyor. This eliminated the need to install a crusher, reducing the construction phase at Deep 1 by six months.

Managing risks

Any new technology comes with risks. The biggest concern around installing the Rail-Veyor, Lessard said, was the possibility the train could go off the tracks, especially at such a steep incline. “We didn’t know what would be the rate of derailment,” he said. “We didn’t know really how to repair derailment.” To mitigate that challenge, they added the safety system and barriers, and have procedures in place for putting the train on track, Paquette said.

The size of the train also presents maintenance challenges. The Rail-Veyor has 182 tires at its 91 drive stations, and more than 400 train cars – 68 on each of six trains – Paquette said. The company has installed sensors for preventative maintenance, and has a large inventory of spare parts to prevent against unexpected failures. Paquette said maintenance staff also regularly check the trains and drive stations to make sure there are no issues.

The system is monitored remotely and access to the rail line is limited to protect personnel. Kelsey Rolfe

The system is monitored remotely and access to the rail line is limited to protect personnel. Kelsey Rolfe

“Since we are the first operator [using Rail-Veyor] we are more careful,” Paquette said. “If we run the Rail-Veyor for five, ten years, we will reduce the inspection. But for the moment we are putting more energy into that kind of stuff than usual.”

Lessard said they are also working to resolve an issue with the tires at the drive stations, which are producing a black “goo” that affects the friction between the tires and the rail cars’ side plates. Agnico is currently working with Rail-Veyor and multiple other companies on a test bench in Sudbury to find a better tire.

Gathering speed

The path to the first underground deployment of the Rail-Veyor in North America has been a long one. The first iteration of the Rail-Veyor was installed in South Africa at Harmony Gold’s Phakisa mine about 10 years ago. According to Ward, after the death of Rail-Veyor’s owner, Risto Laamanen, in 2009, his family struggled to manage the business, and between 2010 and 2011, new investors helped to restart and refinance the company.

“Up to 2015, a lot of time was spent to improve the Rail-Veyor to become more reliable, get the costs down and manufacture it more along automotive standards rather than just fabricate it in a job-shop fashion. All of this was to get it commercially ready for today’s improving mining market.” Ward said.

Rail-Veyor is now installing a surface system at a Venezuela petroleum coke facility and another system underground at a lead mine in southeast Missouri. Ward said it used to be “a struggle to generate an inquiry” from potential customers, but now the news is spreading and the pace of inquiries has increased. “We’re seeing a lot of interest internationally, as well as in North America,” he said.

As for Goldex, Lessard said that one of the major selling points of the Rail-Veyor was that it was expandable. Agnico is currently considering developing other zones at Goldex – the first test stope in the South zone is expected to be in place in June, and the company is spending millions this year on drilling at Deep 2 and 3. “The South zone is close to Deep 1, and it’s a zone that could use the existing installation,” Lessard said. “If we get a ‘yes’ to develop Deep 2, we could potentially add some drive stations and be able to use it there, too.”