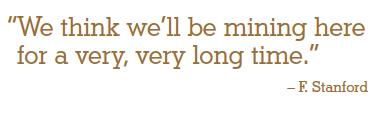

The mine currently has a life of 10 years, but drilling results from the company’s adjacent Media Luna site suggest the property has more gold to spare.

Run-of-mine ore is crushed by identical Metso 42-by-65-foot gyratory crushers in the Guajes and El Limón pits. The Guajes pit currently being mined is easily accessed by haul road. Ore from the El Limón deposit will be crushed in-pit, and then fed to the RopeCon, which delivers the ore to the processing plant. First the ore enters Metso SAG mill (9.15 metres in diameter by 4.15 metres effective grinding length), then a Metso ball mill (7.32 metres in diameter by 12.8 metres long). They grind the ore to 80 per cent passing 60 microns, leading to 86 per cent recovery using a cyanide leach/carbon-in-pulp process.

Loaded with crushed ore heading downhill, the RopeCon actually generates a megawatt of electricity for the mine, while avoiding the most common problems operators experience with conveyors. The railway wheels prevent any tracking problems, and the axles – bolted to the top of the belt – can clear any material that might jam at one end and pierce the belt. There are no rollers in contact with the belt either, eliminating another source of wear. “This technology has eliminated all the different ways you can rip a belt,” said Stanford.

So robust is the RopeCon, added Simpson, the expected life of the system exceeds the planned mine life. Maintenance is mainly to parts attached to the belt, and will be performed at a specially-designed maintenance station at one end of the conveyor. “You rotate the belt forward so that the particular wheelset is in the maintenance bay, pull the power, change it, put the power back on, and turn it again. You can do your preventative maintenance extraordinarily quickly,” Stanford said.

Torex poured its first gold last December.

Training for the future

At ELG, the initial influx of miners and managers came from elsewhere in Mexico, particularly the north, where there are many established mines. But an increasing number of staff – now over 45 per cent of the 200 or so currently working on site – come from the Guerrero region, according to Simpson, and roughly 95 per cent of the mine’s staff are Mexican. The company has no specific target for local employment, but recognizes that maximizing the local workforce is in their best interest. “Over time, we should hold ourselves accountable to get locals trained and experienced enough that they can take the helm,” said Simpson.

Starting in 2013, the company implemented a training program to begin doing just that. Designed by Performance Associates International, it is a program that worked for Simpson at Vale’s Voisey’s Bay nickel mine in Labrador, as well as at other sites worldwide, including Tahoe’s Escobal silver project in Guatemala. As ELG expands its tonnage rates, the locals are beginning to fill seats at the mine, with the mentorship of the experienced miners that Torex started with. “The majority of the plant operators have also come from the local population and have been through this training program,” added Simpson.

Community building

Training and employing some locals is just the start of what Torex has done for a couple of local communities, however. During early negotiations with the local ejidos (communal farms with agricultural rights to the surrounding land), two nearby villages expressed interest in being relocated due to concerns about water availability. For generations, La Fundición and Real De Limón had been precariously perched on the side of the mountain to take advantage of natural springs. However, they lacked the amenities of modern life – no running water, no sewers, and limited electricity.

Moving the villages also turned out to be in the best interest of the miners, as the ideal place for a waste dump would have covered La Fundición, and eventually approached the edge of Real De Limón. Negotiations commenced.

The project included the relocation of two villages at a cost of $30 million.

Three suitable sites were proposed. Architects designed three models of houses for each of the 172 families (roughly 600 villagers) to select from. Construction of La Fundición began in 2013, about eight kilometres from the mine. Resettlement was completed in 2015. The nearby construction of Real De Limón should be completed early this year, with resettlement following shortly thereafter. The total cost of resettling the two villages will come in around $30 million, including the cost to install a water treatment facility and an electrical substation to power the communities.

“The process as a whole was very straightforward and transparent,” said Gabriela Sanchez, vice-president of investor relations at Torex. “What took extra effort from our community relations team was to familiarize the owners of the new houses with the new facilities that their upgraded dwellings provide,” such as gas – rather than wood – stoves, potable water and sewers and garbage collection.

“The relocation provided better schools, clean water, proper sewer facilities, a playground, things like that,” added Stanford. “We put a lot of work into making sure it works for them. The goal is for them to be happy with the move and be happier afterwards.”

Small but steady

The mine life of ELG, according to the feasibility study, is forecast at ten years. But mining could continue at Morelos for decades. In 2012, while completing the feasibility study, a second resource was discovered. The Media Luna project – found “on the first or second borehole”, according to company legend – could add another 7.4 million gold equivalent ounces inferred, including nearly 4 million ounces of gold.

“When we have those two [both] up, we’ll have a beautiful asset,” marvelled Stanford.

The company is pushing forward with permitting to begin driving an exploration tunnel. But with ELG just entering production, Stanford said he is in no rush to spend the $450 million needed to develop Media Luna. “We think we’ll be mining here for a very, very long time.”

Though not in common use in the Americas yet, the RopeCon system, which is installed at half a dozen mines internationally, has the confidence of the Torex executives. The core of the system is a set of high-strength cables and steel framing strung between two towers, similar to the ski lifts that manufacturer Doppelmayr is better known for. Running along a pair of parallel cables are railway-style wheels. The axle of each wheelset is bolted to a 66 centimetre-wide belt. The cables are attached every five metres to a steel support. The conveyor at El Limón-Guajes (ELG) is 1,300 metres long, spanning just over one kilometre between the towers.

Though not in common use in the Americas yet, the RopeCon system, which is installed at half a dozen mines internationally, has the confidence of the Torex executives. The core of the system is a set of high-strength cables and steel framing strung between two towers, similar to the ski lifts that manufacturer Doppelmayr is better known for. Running along a pair of parallel cables are railway-style wheels. The axle of each wheelset is bolted to a 66 centimetre-wide belt. The cables are attached every five metres to a steel support. The conveyor at El Limón-Guajes (ELG) is 1,300 metres long, spanning just over one kilometre between the towers. The mine currently has a life of 10 years, but drilling results from the company’s adjacent Media Luna site suggest the property has more gold to spare.

The mine currently has a life of 10 years, but drilling results from the company’s adjacent Media Luna site suggest the property has more gold to spare.

Torex poured its first gold last December.

Torex poured its first gold last December. The project included the relocation of two villages at a cost of $30 million.

The project included the relocation of two villages at a cost of $30 million.