Luxembourg, which in February announced plans to create a legal framework for space mining, said in early June it would open a €200-million fund to encourage asteroid-mining initiatives. In early May, the small country signed a deal with U.S.-based space research company Deep Space Industries (DSI) to develop a spacecraft prototype to test asteroid-mining technologies.

Just a month earlier in April, northern Ontario firm Deltion Innovations was awarded a Canadian Space Agency (CSA) contract to develop a drill capable of mining for resources on Mars and the moon.

The fund and contracts signal Canada’s and Luxembourg’s growing focus on space mining, which other countries like the United States and China have also been pursuing aggressively. President Barack Obama signed the Space Act of 2015 in November, giving citizens the ability to mine and use resources from outer space. More recently, the United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom signed a partnership to develop and share technology for exploration, and Denmark passed a law in May to regulate activities in space.

“The price point is there and the economics are starting to make sense. I think space mining is going to happen, and it’ll happen because it’s driven by the space agencies, and it will be driven by the private industries very soon,” said Deltion CEO Dale Boucher.

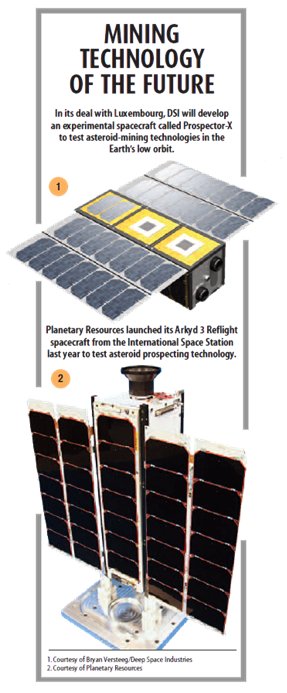

In its deal with the small European country, DSI will develop Prospector-X, an experimental spacecraft to test its technologies in the Earth’s low orbit.

DSI will test three key technologies in Prospector-X to prepare for its Prospector-1 spacecraft: a propulsion system that uses water as fuel, an optical navigation system and an aviation electronics system. “Once we have a confirmation of those technologies we’ll put them into a larger and more robust spacecraft that’s fit for deep space,” said Meagan Crawford, DSI’s vice-president of communications. The Prospector-1 would be sent out to asteroids to survey potential mining targets so DSI can develop the right mining equipment for those asteroids.

Deltion of Capreol, Ontaro is working on what Boucher bills as a “space-age Swiss Army knife.” The tool will weigh about five kilograms, attach to a robotic arm and be able to swap out six parts for different functions such as drilling holes into various rock formations, collecting samples and attaching bolts.

“We’re not new to this particular field and we’ve learned a lot in the last 16 years on how to build space mining equipment,” said Boucher. He said Deltion has worked alongside NASA and CSA to develop drills and excavators since 2000. “By using that know-how we can design into the flight version some of the lessons we have learned.”

The $700,000 contract gives Deltion until the summer of 2017 to build a tool that will be tested in extreme environments on Earth like arctic and desert climates. It will not be ready to fly into space, but could be used as a starting point for further development.

Deltion is also subcontracting to two other Ontario firms. Neptec Design Group will provide engineering expertise as it already has products in space, and Atlas Copco will help with mechanics.

“[Space mining is] really a new frontier,” said Gilles Leclerc, director general of space exploration at CSA. “The purpose is first and foremost scientific. But we do also realize there are applications for resources.”

Technology developed for space can also be used on harsh environments on earth, he said, and though it is likely at least a decade away from being a reality, the future market of space mining could have huge potential for Canadian companies.

“Whoever is going to be first to exploit space resources is really going to have an advantage,” Leclerc said.

For Boucher, space mining could also be valuable for getting resources like water to astronauts.

“In order to explore beyond the space station, or get anywhere off the planet, we have to be able to carry our supplies with us,” he said. “But the further explorers go, the more it costs to get water out to them.”

Crawford, too, said DSI is primarily looking to access the water in asteroids. “Water is important for human habitation, for drinking water and air, and radiation shielding,” she said. “But also in its basic parts it becomes hydrogen and oxygen; it becomes rocket fuel. There’s a lot of potential energy in water.”

It costs up to $50 million per metric tonne to transport fuel into space, according to Chris Lewicki, CEO of Planetary Resources, which last year launched its Arkyd 3 Reflight spacecraft from the International Space Station to test its asteroid prospecting technology.

Mined materials could also be brought back and sold on Earth, including potential fuel resources for the future. For instance, Boucher said, helium-3 gas is anticipated to fuel new nuclear fusion power plants. The gas is available on Earth, but not in large quantities. It is, however, found in significant quantities on the moon.

Asteroids are expected to contain iron, nickel and cobalt, and platinum group metals could occur in the space rocks in quantities “hundreds the times” of even the most productive mines on Earth, Lewicki said.

But if and when space mining happens, it could open up a diplomatic can of worms. Leclerc said international rules under the United Nations, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, currently state that space belongs to everyone and prevents celestial bodies from national appropriation.

“So there is a clash between what you can claim for commercial exploitation versus ownership,” Leclerc said. “The international framework has not been established.” In the meantime, he said, there is plenty of science to be developed to better understand the moon, asteroids and other bodies that could be exploited.

“It’s an intriguing aspect but one that could potentially be disruptive.”