Caterpillar’s Rock Straight System uses picks that target the tensile strength of the rock. Courtesy of Caterpillar

Continuous mining systems have been established in coal and soft rock mining for about a century now and the technology to cut through hard rock has been successfully used in civil engineering projects since the late 1950s. One would think that by now, continuous hard rock mining would also be a reality but it is not. The possibility of the technology being applied to hard rock mining has in fact remained stuck between a rock and a hard place for a very long time – until now. Drilling and blasting finally has an emerging competitor.

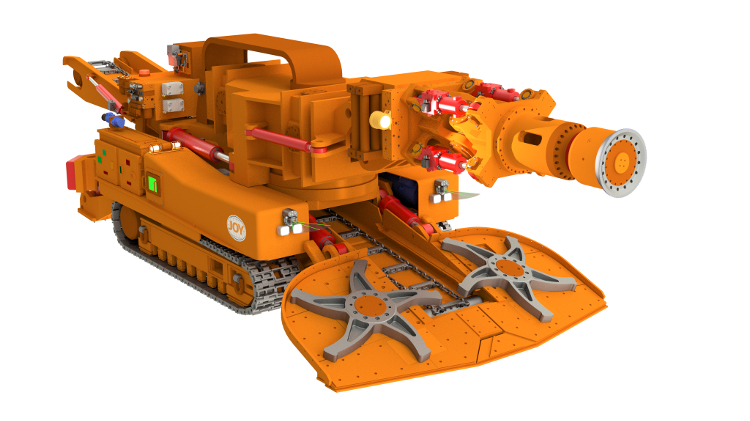

Last September at MINExpo 2016, Caterpillar commercially launched the Cat Rock Straight System, a fully-mechanized longwall system for continuous hard rock mining that features the cutting- edge HRM220 hard rock miner. While Caterpillar is the first to reach commercialization, it is not the only one striving to develop the technology. Atlas Copco, for example, began working on its new generation Mobile Miner continuous hard rock mining technology with Rio Tinto in 2009. It has been working with Anglo American on the development of a continuous hard rock mining system, in a project named Rapid Mine Development System (RMDS), since 2012. Testing of the RMDS at an Anglo American mine began in 2016. Those tests are close to completion and Atlas Copco is planning a formal commercial launch later this year, said Mikael Ramström, Atlas Copco’s director for mechanical rock excavation. As well, Joy Global, now Komatsu Mining, has been testing the prototype for its DynaMiner, which features DynaCut hard-rock cutting technology, since September 2016 with very promising results, according to the company. Sandvik is also developing a continuous hard rock miner called the MX650, but declined the opportunity to discuss its work with CIM Magazine.

Different approaches

The biggest problem with mining hard rock is that it is difficult to break mechanically and that poses challenges in advance rates and energy use, not to mention how quickly it wears down cutting parts. Each manufacturer is using a different approach to increase the wear life of components and reduce the time and energy it takes to break the rock. Caterpillar’s HRM220 has numerous picks mounted on two cutting heads to hit the rock from an angle designed to exploit the rock’s tensile strength, which is 10 to 20 per cent of its compressive strength. “The movement, or activation, of the cutting tool enables each pick to hit the rock with momentum like a hammer,” said Jens Steinberg, commercial manager of hard rock cutting for Caterpillar Global Mining. “The contact is very short and it limits pick heating and wear. The movement is achieved by superimposing rotational movements.”

Redpath debuts 1.8-metre boxhole drilling in Indonesia

Atlas Copco feels its way into autonomous loading for LHDs

Komatsu Mining’s DynaMiner, on the other hand, employs a DynaCut disc mounted to a smart boom that oscillates. Using an undercutting method, the system chisels the rock with action reminiscent of a heavy, high-speed hammer that exploits the weaker tensile properties of the rock as well.

Like the DynaMiner, Atlas Copco’s Mobile Miner uses disc cutters, a technology based on what is used in conventional tunnel boring machines. The company continues to refine the technology. “You have to tune your machine to excavate rock at a certain speed and that speed is very much dependant on the hardness of the rock,” said Ramström. “You can have discs working at a very high speed but that increases the wear on the parts, so you try to tune the machine for that specific rock hardness.”

To do this, the Mobile Miner uses sensors in its hydraulic system that monitor how the rock is responding to the pressures and adapts the force accordingly. In fact, modern computer and sensor technologies are being used in all the new hard rock miners for more intelligent and efficient cutting in machines more compact than those used in conventional tunnel boring.

Atlas Copco collaborated with Rio Tinto to develop the Mobile Miner. Courtesy of Atlas Copco

Smaller, more flexible machines

“As we’ve refined the technology, energy in and cut rock out has improved dramatically – meaning a smaller, lower-mass, lowercost mining machine,” said Brad Neilson, president of hard rock mining for Komatsu Mining. “Machine size and mobility is important for our customers, so we have focused on keeping it simple and compact.”

Not only do compact hard rock miners reduce energy costs, they also make it far easier to excavate sharp breakaways and cross cuts than it is for a larger conventional machine used in civil engineering. As well, “in civil engineering, when you’re excavating hard rock, you’re only dealing with one tunnel but in mining you have different tunnels,” said Ramström. “So you need to have a technology that is smaller and flexible and can move from place to place.”

Long journey

All the technologies have been a long time in the making. Caterpillar first embarked on developing hard rock cutting technology at the beginning of the millennium with underground cutting tests in South Africa and later in Caterpillar’s Luenen, Germany facilities. Once the Rock Straight System was developed, it was tested in a mine in Poland. Komatsu Mining has also traveled a long journey in its research and development, beginning in 2006 when the company first acquired the license for new hard rock cutting technology developed at Australia’s mining research and innovation centre, CRCMining.

“Working with industry partners, Komatsu Mining has spent years refining the technology to provide the mining industry a viable alternative to drill and blast,” said Neilson. From validating the cutting technology in a full-scale test rig in South Africa to almost five years of underground testing of its hard rock continuous mining system, the company has verified, studied and improved on everything from the life of the components to material handling, control and automation. Currently, the DynaCut prototype is being tested underground at Newcrest Cadia East Mine in Australia to quantify instantaneous cutting rates in very hard constrained rock to estimate process advance rates and to fine-tune the DynaMiner for commercialization.

Meanwhile, Atlas Copco is testing its Mobile Miner and RMDS continuous hard rock mining system at an Anglo American mine. “We are in a situation where we are proving the first machines in a production environment, not in a test environment but in a real mining environment” said Ramström. “We had to be convinced that the whole system could deliver. We knew the technology has been proven in other types of environments but now that we had a new system, we had to prove the system.”

Komatsu Mining's entry into continuous hard rock mining is the DynaMiner which uses disc cutters. Courtesy of Komatsu Mining

Between the rock’s hardness and the industry’s resistance to change

To understand a key obstacle to the development of continuous hard rock mining, one has to go back to 1977, when the Robbins Company – which invented the world’s first hard rock tunnel boring machine two decades earlier – saw the opportunity to adapt its technology for hard rock mining. Within a few years, the company had built the first prototype for the Robbins Mobile Miner, a futuristic machine for its time with sophisticated technology that fractured the rock with steel disc cutters mounted on a rotating wheel.

The first Robbins Mobile Miner was commissioned by the Mount Isa mine in northwest Queensland, Australia, in 1983. With an advanced rate of up to 80 metres a month, the miner excavated 1.1 kilometres at the mine. Later, it was purchased by Pasminco’s Broken Hill mine in New South Wales, Australia, where it advanced 1.4 kilometres. In 1993, the year the company’s tunneling division was acquired by Atlas Copco, the Mobile Miner was also used for a civil engineering project in Japan. While the Robbins Mobile Miner had its weaknesses, including short life on wear parts, overall, the technology was proven and successful. Yet no more customers followed. Robbins/Atlas Copco had built the continuous hard rock mining machine and no one came knocking. By 1998, Atlas Copco shelved the technology.

“It’s a very conservative industry,” said Ramström. “That was and is the biggest challenge to introducing new technologies. It is the change process that is really tough, not the technology itself in this case.”

In the last decade, however, the industry’s resistance to change has softened. Given the challenging and volatile economic environment since the recession, more and more mining companies are prepared to entertain technologies that can improve operations and cut costs.

“This time, the interest is coming from the mining companies,” said Ramström.

The benefits

Continuous hard rock mining systems offer the potential for easier scheduling, much safer and faster advance rates and greater productivity than conventional drill and blast, which averages about five metres per day.

“We are seeing our technology can achieve 10 metres a day,” said Ramström. “With drill and blast you have to stop for blasting and you have to bring in a lot of different machines into the mine. You drill, you blast, you ventilate and you secure the roof with rock bolts and or mesh, you have to bring in loaders and mine trucks and do all this before you can move in another five metres. If one of the machines is not available when you need it, the whole tunnel cycle stops and you can lose a lot of time.”

Because continuous mining rock fragmentation is far more consistent compared to drill and blast, continuous hard rock mining machines can also improve milling and eliminate the need for primary crushing, according to Steinberg.

Decades’ worth of research and development are making continuous hard rock mining a reality. The technology continues to advance, chipping away at the miners’ resistance to an innovation that could remake the underground mining industry.