At Skouries, shown here, development work is underway to prepare for both open-pit and underground mining | Courtesy of Hellas Gold

Eldorado’s Skouries project, set to enter production in 2017, could define a new era for the Halkidiki Region in northern Greece. Along with the new open pit mine being developed, historic tailings are being reprocessed, industrial lands are being reclaimed and Eldorado’s subsidiary, Hellas Gold, is intent on building a leading gold mining jurisdiction in the municipality of Aristotelis. But with Greece in political and economic turmoil, every small step forward is being carefully placed.

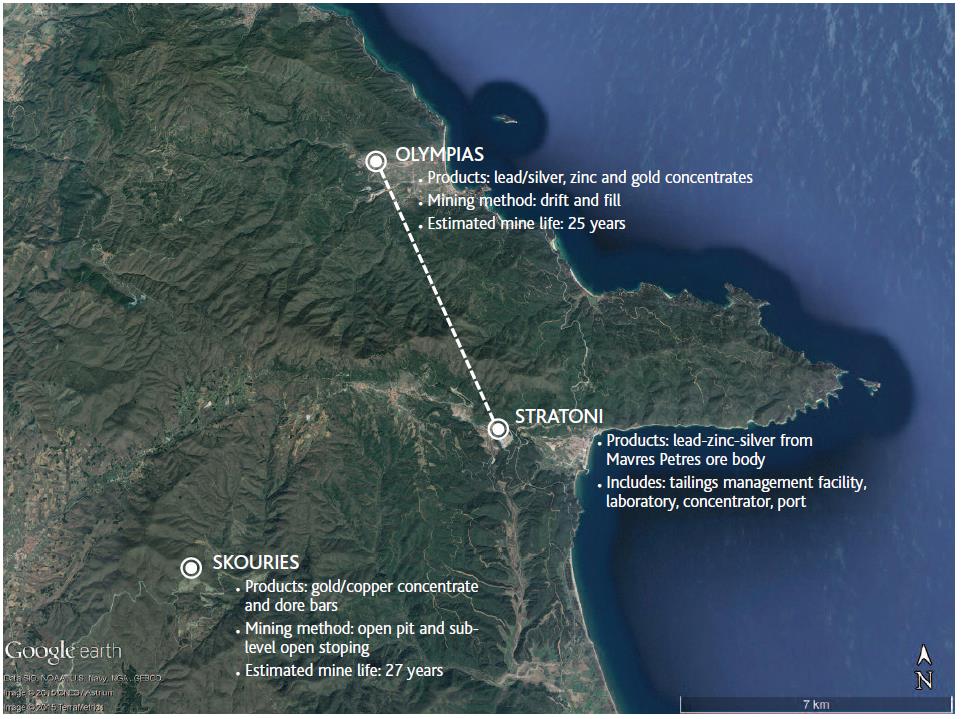

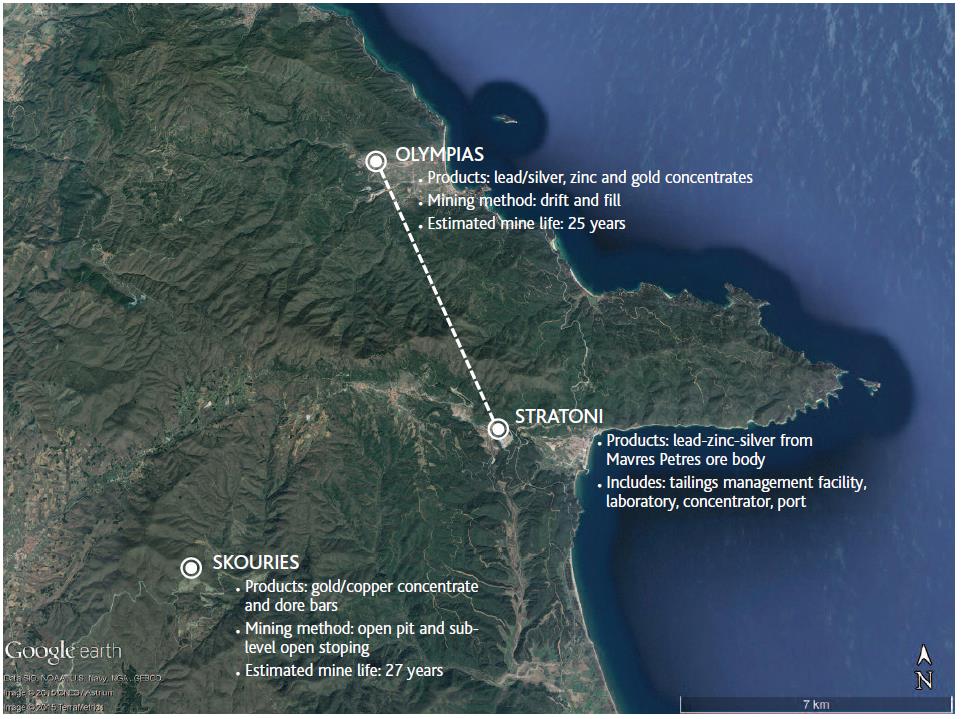

Millennia-old mining artefacts dot the sides of the road as we wind our way up the steep hills from the small seaside town of Stratoni to Skouries, Greece’s newest gold mine. “For us, this is going back to our roots,” said Mihalis Theodorakopoulos, managing director of Hellas Gold. He has been working on the Kassandra mines, which includes the Skouries, Olympias and Stratoni assets, for more than 25 years, long before they were ever owned by a Canadian company (the first was TVX Gold in 1995). Eldorado’s nearby Mavres Petres silver-lead-zinc mine – part of the Stratoni facility that also includes a processing plant and port – has been in near-continuous operation since the sixth century. And while miners have always made up a significant portion of the local population, Eldorado’s Greek projects now employ around 1,700 people in a municipality of about 18,000. Unemployment in Greece currently hovers at around 26 per cent. As much as it is a throwback to the old ways, this project is more about rebuilding Greece as a modern country.

Metallurgical master key

With the entire Kassandra mines project approved under one environmental impact assessment, Eldorado’s vision for the area is long-term and broad in scope. Because it does not produce gold, Stratoni might otherwise seem like an odd fit for Eldorado, but the existing mine site is central to the way the company is simultaneously developing its Olympias and Skouries assets. “The idea was to create one mining centre,” said Theodorakopoulos. “Instead of having three, let’s connect them all in one place. The connecting link between all these things is the metallurgical process.”

The Olympias flotation plant Courtesy of Hellas Gold

That connection is taking some time to build – about seven years from now is when Eldorado expects facilities to be ready at Stratoni to treat ore and concentrate from the Olympias, Skouries and Stratoni operations.

Gold from the Olympias mine is refractory, so Eldorado is planning to build a flash smelting plant at Stratoni that will treat a mixture of copper and pyrite concentrates using technology provided by Outotec. Flash smelting is a process designed to produce copper with gold as a byproduct, so naturally it requires copper in order to work. That copper will come from the Skouries copper-gold porphyry deposit and its associated concentrator. Olympias ore will be refined to produce lead/silver, zinc and gold concentrates. The gold concentrates from Olympias and the copper concentrate from Skouries will be combined in the flash smelting process. For all of this to come together, an eight-kilometrelong ore transportation tunnel connecting the new plant with Olympias’ underground workings will need to be completed.

The two gold-bearing deposits are of very different geological character. While Skouries is relatively high grade for a porphyry ore body, with reserves at 0.76 grams per tonne of gold and 0.51 per cent copper, Olympias’ polymetallic carbonate replacement ore body is much richer. There, reserves are measured at 7.56 grams per tonne, with 128 grams per tonne of silver, 5.7 per cent zinc and 4.3 per cent lead – numbers that are counterbalanced by the difficulty in processing the refractory gold. The codependent relationship of Skouries and Olympias makes both more economic, but processing Olympias’ ore at Stratoni and away from the town of Olympiada is also motivated by environmental concerns. The past-producing mine left a large footprint, with old tailings taking up space. As the mine’s old workings are being refurbished to support modern operations, the tailings too are being treated and reclaimed. Remaining gold is being extracted, creating backfill for mined-out areas, and dewatered new tailings are being moved to the active tailings facility at Stratoni. It is likely the only chance the municipality has at having the historic Olympias site returned to something like its original state without footing the bill, and though Eldorado is not making any money reprocessing tailings, it is at least gaining social credit.

Eldorado’s shareholders want to see a return on their investment, however, and the company is about to make a major transition in terms of economics. Next year, should the project continue, the company expects to turn a profit in Greece for the first time. The mill and concentrator at Skouries are in construction now, though the government recently revoked permits for the plant’s completion, and pre-stripping is ongoing for the open pit, with commercial production expected in 2017. “In Skouries, 30 per cent of the gold is free, so with a gravity circuit, this gold will be produced from the first day of production,” said Theodorakopoulos. “The other 70 per cent of the gold will report to the copper concentrate and for the first six to seven years it will be sold to external smelters. When we have our metallurgical plant [at Stratoni], up to 30 per cent of the produced copper concentrate will be co-treated with the Olympias concentrate.”

Ore from Olympias will travel through an eight-kilometre tunnel to be processed at Stratoni

Multi-tasking

When I was on site last September, Greece’s head of operations for Eldorado, Britt Reid, and his operations team were also there, taking a look at how progress was being made and chomping at the bit to take over from the construction team – though that would still be over a year away. Bulldozers were moving earth to prepare the tailings management facilities, and a crew was installing drainage wells and injection wells to divert groundwater from the ore body for the start of production in the open pit. At the same time, development was ongoing for the underground operations that will replace production from the open pit about seven years after startup. “We’ll get there,” Reid assured me.

Skouries will be the first open pit gold mine ever attempted in Greece. The project has been designed to minimize its footprint, limiting the total surface disturbance to 180 hectares. SRK Consulting was brought on to determine the optimum balance between open pit and underground mining. Theodorakopoulos explained that it would have been possible to keep the mine entirely underground, “but that would have meant we couldn’t use the open pit as a tailings disposal area, so we’d have to create another tailings facility and occupy about 700 hectares.” He added that open pitting the entire deposit would have meant occupying 1,600 hectares.

With all the preparation underway at Skouries, Olympias is equally under pressure to start mining next year. This November Konstantinos Markogiannis, the plant manager at Olympias, will start refurbishing his equipment in order to treat feed from the mine once all of the historic tailings have been reprocessed. “We’ll stop for six months in order to install the new equipment and modify the plant,” he said, estimating that it will be ready for production next May. His team is accustomed to change by now, having had to refit the plant first to process tailings and even within that process to tweak it on a monthly basis. For example, slimes found in the old tailings posed a dewatering challenge for disc filters. “If the concentrate is below 20 grams per tonne the material is not saleable or the penalties are very high,” said Markogiannis.

Filter presses will figure into Markogiannis’ plans with run-of-mine ore as well. Until the drilling contractor Aktor finishes the tunnel to Stratoni, dewatered fine tailings will be trucked to the Stratoni tailings facility while coarse tailings will be used as cemented backfill, so new filter presses will be added to support the Olympias mill’s throughput of up to 400,000 tonnes per year.

Joel Rheault, general manager of the Olympias mine, is overseeing the development of untapped resources at Olympias and the widening and heightening of old drifts that can still be of use. A native of Atikokan, Ontario, Rheault moved with his wife and three daughters to nearby Thessaloniki. He is not likely to run out of work. “There’s a lot left,” he said, examining the mine plan with glee. Previous mining only reached the upper half of one ore body, and left a second deposit a few hundred metres to the east untouched. Rheault said he and his team hope to be there soon enough: “The east ramp will open up multiple work headings to us to start driving towards the [east] ore body.”

Greek political theatre

With so much work ongoing at Eldorado’s operations, it is hard to come to terms with the sabre-rattling of the Greek government (see “Greece adds hurdle for Eldorado’s Skouries project,” p. 32). According to Eldorado, the mines will offer more than 5,000 direct and indirect jobs once they are in full production at a time of painful economic realities in Greece.

Eldorado has worked to build relationships and show a Greek sense of hospitality. The local culture is one in which coffee breaks stretch to accommodate social requirements, and no meal is complete without company. But pioneering modern mining techniques in a tourism-oriented economy is not without its challenges. “Changing hearts and minds takes time, patience and a lot of dialogue,” says Eduardo Moura, Eldorado’s vice-president and general manager of Greece. To familiarize local residents with its operations and environmental commitments, the gold miner has welcomed more than 4,000 people to its Halkidiki sites in the last year alone. Students come by the busload, and the company’s PR manager, Kostas Georgantzis, told me they are seeing major improvement in public sentiment, but the company faces a constant uphill struggle.

At the moment, a lot of the tension surrounding Eldorado’s operations seems to be coming from the chaos of Athens, rather than the local parties. Political divisions in the country are now contested with a fiery and even violent passion that is difficult to reconcile with Greece’s reputation as the birthplace of democracy.

In the municipality of Aristotelis, however, there is hope that things can settle down as the benefits of Eldorado’s projects continue making their mark on the surrounding communities. “We have a new mayor whose main election slogan was ‘Let’s reunite the area,’” Theodorakopoulos said, adding that groups that had traditionally been anti-mining have gotten behind this new leader and may be more open to seeing what the company’s operations are really like. It is perhaps in this small way that a country gets rebuilt.

Ore from Olympias will travel through an eight-kilometre tunnel to be processed at Stratoni

Ore from Olympias will travel through an eight-kilometre tunnel to be processed at Stratoni