A short solution for the long haulTransitioning from information overload to efficient operation with short interval control

Mining companies have been collecting data for years, but it is only recently that they have started to figure out how to integrate, process and act upon that information.

“There’s probably a 25 to 30 per cent productivity improvement available at most mines,” said Jim Gallagher, president and CEO of North American Palladium. It is a shocking statement, but he has the numbers to back it up. Gallagher said his mine, the Lac des Iles palladium operation, is seeing trucks and other equipment moving for 10 or more hours out of a 12-hour shift in the underground, compared to six hours in conventional mines. With kilometres of one-way tunnels and often a single access point for personnel, hours of downtime is usually thought of as a given in underground mining. So what’s the secret to the huge improvements at Lac des Iles? Something Gallagher calls real-time mine management, otherwise known as short interval control.

This concept involves, basically, checking in with what is happening underground on a more frequent basis than has traditionally been done. Then, with the information gathered from each check in, making quicker decisions to improve workflow in the mine. This could be as simple as a radio call every hour or two, but at its most exacting would see every activity in the mine continuously monitored digitally, that data fed into an algorithm and the mine plan automatically optimized in the short-, medium- and long-term to better achieve a company’s strategic goals. In many mines, it can still take 12 hours for information to make its way to the surface, even when plans go smoothly underground.

Lac des Iles is an operation near Thunder Bay, Ontario, that has been producing for more than 20 years. That makes it a good case study when considering the power of implementing modern technology and ideas. Late last year, the team at Lac des Iles began “putting things in,” according to Gallagher. Things like fiber optic networks, wireless hubs, sensors and tracking devices. Early this year, the mine implemented underground equipment tracking. “I don’t think we’ve spent over $300,000 to date,” Gallagher said.

Despite the low price tag, the improvements made are so powerful that Gallagher predicted that five years from now nobody will contemplate building a mine without real-time mine management.

Related: New leadership and technology at North American Palladium inspired a digital revolution

Making (good) decisions quickly

Mining is unpredictable, and most will admit that a mine plan rarely gets followed to a T. Things break and crews improvise, essentially creating a new mine plan on the fly. “Who’s to say that that shift boss, at that point in time, is putting forth the optimal plan?” asked Gallagher. “That’s not a comment on individuals, because that’s a tough task to do, to really optimize those resources.” How could a shift boss see, in the moment and without any help, the best move to make in terms of the business plan?

Over the past couple of years, mines and mining equipment suppliers have been collecting an increasing amount of data, what Paola Telfer of Vandrico calls the “big data side” of things. Switching to data-driven decision making, however, has been slower to arrive. Telfer is the chief commercial officer and one of the founders of the Vancouver-based tech company. She said that until now miners have had access to “a lot of tools for post-hoc analysis,” but not real-time help.

|

|

Vandrico's ConnectedWorker Replay software pulls data from any type of sensor in a mine and allows managers to replay events. Courtesy of Vandrico

|

As much as new tools are helpful, some argue that short interval control should be seen as both a technological change and a cultural one. “The core problem most operations have is they’ve gone and spent a whole lot of money on complex IT systems for engineers and accountants but nothing on getting a short interval plan to their supervisors so they can lead their teams to deliver it,” said Paul Moynagh, CEO and co-founder of Commit Works, an Australian software firm specializing in short interval work planning and execution. He recalled the example of a company based in Australia that spent AU$3.5 billion on an enterprise technology system but still had underground operators reviewing photographs of a whiteboard during their shift.

According to Moynagh, it is almost impossible to get supervisors and crews to execute short interval control if they do not get a shift plan that takes account of all the work that will influence their performance. For example, maintenance, training and services work may get in the way of hitting targets for a shift. If this is not reflected in the plan, the crew will not commit to delivering the plan regardless of the data that is coming off the machines in real time.

Gallagher said he has experienced friction with the social change that comes with more computer involvement. “The front line supervisors, some of them adapt well to this and some of them resist because they used to dictate what went on,” he said. “We’ve had some pushback on that, and we continue to work through it. The relationship between mine planning, the control room operator and the shift boss is still being worked out, but we’re on the front edge of this.”

In a morning meeting in August, supervisors at the Lac des Iles mine reported that the ore passes were empty. “They relied on the estimation of operators working in the area,” recalled David Galea, manager at North American Palladium. The operations team agreed with the maintenance team that it was a good time to get some maintenance done in the shaft, knowing that trucking would not be impacted for several hours until the passes filled up again. The plan for the day was made and workers dispatched, but then the mine coordinator checked the ore pass measurements digitally. Contrary to what was reported, the passes appeared to be nearly full, so shaft maintenance was shortened.

Overcoming the fear of being watched

Part of the issue with all real-time data has traditionally been a reluctance from workers to be tracked while on the job. “One of the cultural changes that organizations have to get through is mine operators don’t always want that level of visibility,” Gallagher said. “But as soon as we started tracking truck movement, we saw performance improvements.” He claimed that the safety benefits associated with tracking are overplayed in an effort to skirt the obvious: your boss knows everything you do. “We have been very front and centre in saying ‘Yes we are tracking movement and performance,’” said Gallagher. “We started dealing with the positives – recognizing operators that have high performance. We have purposefully chosen not to go after those who are on the low end of the scale.”

Related: Wearable tech may lead to increased safety for operators, but at what price?

Gallagher noted his operation still has lots of room to grow. Although managers are able to track progress and amend plans, operators cannot see their statistics in real time yet. If operators have their performance data on hand it can be a powerful motivator and also help them to understand what behaviours really do increase productivity. Beyond that, “The ultimate step is getting computer help with planning and scheduling and, as things change, the computer updating the schedule in an optimized way,” Gallagher said.

That machine learning aspect of digitization is something Vandrico’s Telfer said will have the biggest impact. Her company makes software called Replay that allows a manager to replay events in a mine and see where people and machines were and how they moved. Vandrico’s software pulls data from virtually any kind of sensor. “We’ve gone through a lot of pains to make the tools very Google-esque,” Telfer explained. “Underneath our modules is a platform based on open data.” If a deviation from the plan is noticed, she said, managers can figure out the root cause and make corrections. In the past, she said, doing the same thing might have taken a long time to gather data and involved hiring consultants to analyze it.

She brought up the example of a Canadian mine where KPIs were not being hit, with tasks taking 100 per cent longer than expected. It took several weeks of data collection and analysis, along with interviews with workers, for managers to figure out that a jumbo had been blocking the way while waiting for maintenance. “Workers would arrive, leave again and then take a detour to bring items little by little to their site,” she said. Nobody was investigating in real time, and the pattern was difficult to recognize. “Everything is just so loud, there is a lot going on, everyone is busy and focused on their own thing, communication cuts in and out sometimes and it takes a long time to get between places. So you don’t really want to chit-chat or get distracted or get into someone else’s work order if you don’t have to.”

If a computer application had captured the length of time things were taking and analyzed the irregular patterns of movement, it could have alerted the workers, or even assigned them different tasks.

The Godfather

“We’re not out to do it for the recognition,” said Rick Howes, who has become a touchstone in the field of digital mining technology, and particularly short interval control. As president and CEO of Dundee Precious Metals, and formerly as general manager of the company’s Chelopech gold mine in Bulgaria, Howes brought the 50-year-old operation into the modern era. “Ever since people heard about what we were doing, there have been something like 40 to 50 mining companies visit the site,” he said.

In 2009, Howes began a plan to “take the lid off” of the Chelopech underground operation by tracking machines and people, and installing Wi-Fi throughout the mine without an enormous financial outlay. “The first phase was just getting connectivity to our mobile fleets,” he recalled. “Now though, the real power is advancing the use of the data.”

This August, Dundee purchased MineRP and folded its new technology venture, Terrative Digital Solutions, into the company. MineRP is an enterprise resource planning (ERP) software suite designed for the science aspect of mining, which works with traditional ERPs that help manage the business side. Traditionally mining companies have been unable to fully take advantage of traditional ERP software because it cannot be properly integrated with many mining technical applications used to model, design, plan and control the mine. “The combination of the Terrative Digital Solutions real-time connectivity and the MineRP enterprise software platform can be transformative for mining companies,” Howes explained.

In addition to spawning new companies, those involved with Chelopech’s technological retrofit have made the transition to other ventures, and have begun to see digitization concepts become more broadly applied. Gordon Fellows, the former technical services manager at Chelopech, is now project subject matter expert for short interval control and task management at Barrick Gold. Since August of last year he has been based in Nevada and deeply involved in what Barrick calls its “Digital Transformation.”

It’s not fringe when Barrick is doing it

In many ways, the fact that Barrick sees promise in short interval control means the concept has hit the mainstream and is poised for global uptake. The gold giant is piloting a number of projects at its Cortez operation, and has taken up the reins in automated hauling, underground Wi-Fi, and developing a number of new apps to implement short interval control. Whereas Lac des Iles has gone with what Gallagher calls the “80:20 rule” of digitization, wherein the company gets 80 per cent of the benefit for 20 per cent of the spend, Barrick is pushing the envelope of the tech. “We’re going beyond Chelopech,” said Fellows. “There’s a lot more capability and more customization: our operators can actually pull up a map of the underground mine.” They can see where other machines and people are in real time, instead of traveling an hour or two only to find that something or someone are not where they are supposed to be. In the future, operators may be able to view the mine in a way that is similar to Google maps, with traffic incidents reported and quicker routes suggested.

|

|

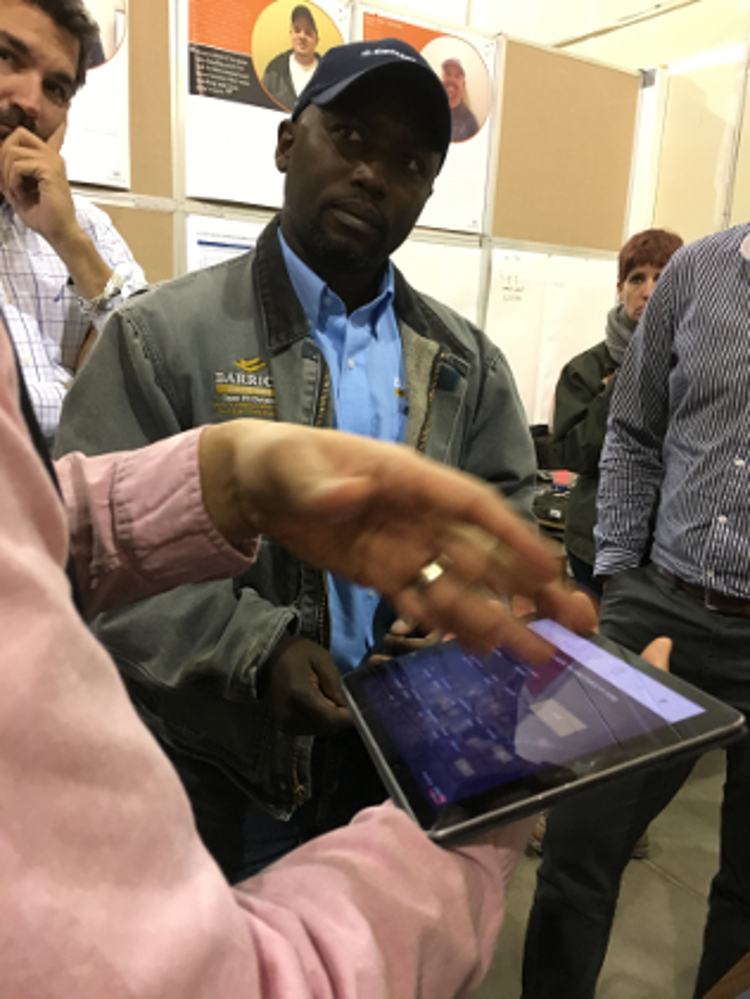

A Barrick employee gives feedback on the underground short interval control system to a software developer at the company's CodeMine in Elko, Nevada. Courtesy of Barrick Gold

|

At the moment, Barrick has released what it calls a “minimum viable product” across the Cortez underground, with the understanding that the company will not stop developing further tools. Barrick is working with Cisco and Microsoft to continue development, but is also pulling together a crack team of tech wiz kids in-house to work on development. The company has, to date, created separate apps for eight different kinds of machines, each customized so that operators can see their progress with respect to the plan as they go along. Asked why they developed their own tools, Fellows said, “For Barrick, we just didn’t see the products out there on the market.” For example, with Barrick’s software, a bolter can see live how many bolts they have done already and how many are left to do in the plan, and the supervisor can be aware if work is ahead of or behind schedule. Then, he or she can shift plans to suit the real-world conditions.

Fellows also said that since his work at Chelopech some five years ago, technology has advanced and gotten cheaper. “The concept and acceptability of apps has come a long way,” he said. “The software on the tablet on the machine looked the same for every piece of equipment [at Chelopech]. Here we’ve got a separate app and it’s much more customized. The whole internet of things has standardized the exchange of information, which makes things a lot faster too.”

Adopting new technology is changing the type of people Barrick is looking for, as well as the demographic. “In addition to talented miners, I need a lot more technical people, I need a lot more computer-savvy people and I need people who are adaptable to change,” said Curtis Cadwell, general manager of operations for Barrick Nevada. “In the past, it’s been about just getting bigger. My dad worked in mining, and when he was younger a 50-ton truck was a big truck. When I started, a 400-ton truck was kind of the biggest size. My kids are getting into it and I already told them: ‘You’re not going to see a 2,000- or 3,000-ton truck. You’re getting into physical limitations. But using the entire clock and being smart and using your data is how you’re going to improve.’ It’s much more about quality, repeatability and analyzing data.”

Dundee’s Howes agreed that tech implementation can have an impact on hiring. “For sure the impact on HR has been huge,” he said. “We get a lot of interest now from people – especially from the younger generation. We don’t get much turnover in the company.”

A new model

For all of the speed they promise, it is not guaranteed that digital tools will create positive change if they are used improperly or without vision. And implementing tools hastily can lead to mistakes “The mining industry can’t figure out how to move faster towards moving faster,” said Howes. “Words like ‘agility’ do actually mean something. It’s not just quicker, it’s quicker and smarter.”

Howes said that the buzz around digitization can sometimes lead mining executives to make hasty decisions. “People are worried they are going to miss out and get outcompeted,” he added. “You have to be careful – there are all kinds of ornaments and neat toys available now. But the critical thing for companies is to figure out what they are trying to do. Without a tree to hang it on, an ornament is not going to help the business get better.”

Looking to get into short interval control?

The Global Mining Standards and Guidelines Group (GMSG) has been putting together guidance.

In September, the Canada Mining Innovation Council (CMIC) and GMSG kicked off a workshop intended to develop a framework for companies interested in pursuing short interval control. “The idea is that we pull together mining companies, suppliers and consultants,” said David Sanguinetti, CMIC’s innovation manager for underground mining. “People are interested in it, but there is no roadmap, nothing that tells them how to do it.”

The process of implementing digital controls can seem daunting because there are no truly off-the-shelf solutions, according to Sanguinetti. “You’re going to need an assortment of pieces, and then you’re going to need to integrate them,” he said. “The guideline is to provide somewhere to start, rather than replace consultants or suppliers; it’s a roadmap.”

The basic components

1. Sensors on everything you can afford

2. Underground Wi-Fi or LTE (a possibly lower-capex solution once telecoms can offer it)

3. Software to not just collect, but also interpret the data

4. People who are motivated to change their behaviours in the pursuit of better performance

*****

This was one of our favourite stories of the year. To see the full list, check out our Top 10 of 2017 editors' picks.

More Technology

The automation revolution

There is no doubt the future of mining is automation. But what does that look like, and how will we get there?

The future of flotation

Buoyed by pressure to cut costs and improve recovery, new flotation technologies are on the rise