The actions we take today will determine mine closure outcomes and the social acceptability of the industry for future generations. When changes are made in areas that impact life-of-mine (LOM) strategic decisions and those impacts are undervalued, the accumulation of these decisions can result in unacceptable mine closure residual risks.

Changes following mine construction are inevitable (e.g., mine reserve estimate updates, mine waste re-classification, water management infrastructure changes, disturbance footprints, predicted to actual performance, etc.), and are part of improving operational efficiency and adaptive management. But long-term planning objectives can be overshadowed by short-term production and compliance key performance indicators. Although both are important, when long-term planning objectives are not properly managed, operators can lose sight of mine closure objectives and be unaware of risks that accumulate over time, such as improper mine waste characterization, unidentified surface water and seepage pathways, and changes to community expectations for post-mining end land uses.

Industry pressures can also influence strategic decision making during operations, which affects closure planning outcomes. Market cycle fluctuations, for one, can result in stretching available resources and prioritizing short-term goals over strategic planning. During downturns, focus typically shifts towards operational compliance and production risks. During upturns, priorities can shift towards resource expansion with schedule-driven goals. Both fluctuations may include new ownership through mergers and acquisitions, which also introduces change.

Additionally, regulatory creep and operational compliance can result in permit conditions that are not aligned with closure objectives. And internal operational pressures, such as competing priorities, silos between departments, team continuity issues caused by staff turnover, and a growing knowledge gap due to the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation can make strategic long-term planning difficult.

The impact of changes made during operations may not be fully recognized until later in the LOM or into closure. Recent examples of how poor change management has contributed to unintended consequences are the tailings dam failures at Mount Polley in Canada and the Fundão dam in Brazil. The independent post-mortem assessments highlighted change management issues such as poor observational approach methodology, key personnel changes, and a lack of integrated mine planning and water balance as contributing factors to the dam break failure modes. While these two incidents occurred during operations, the same residual risk can extend to post-operation.

The Association of Change Management Professionals (ACMP) defines change management as “the practice of applying a structured approach to transition an organization from a current state to a future state to achieve expected benefits”. Mine closure planning shares a similar definition although it is often not thought of as the same process. When it comes to mine closure planning, “achieving expected benefits” is typically promoted as a conceptual ideal: broad-brush, feel-good statements of relinquishment of post-mine landscapes, sustainable closure solutions, and stable and non-polluting landforms. In reality, closure hazards, such as physical and geochemical stability, and desired end land use generally result in residual risks that require active care and maintenance by the owner and long-term financial liability.

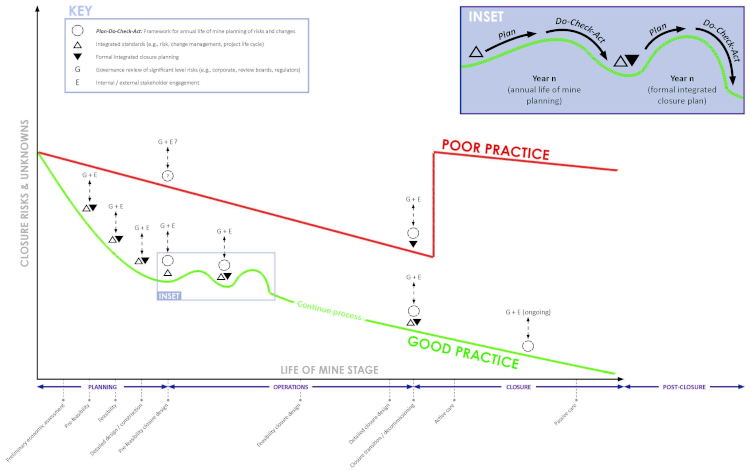

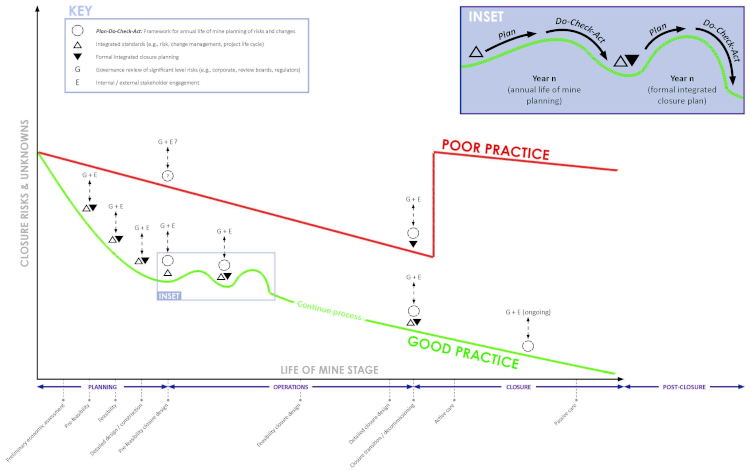

There are various practices over the LOM that may increase a mine operator’s adaptability during change, reducing the potential of known or new residual risk to creep in. A Plan-Do- Check-Act framework (see below) is a useful model for managing change and can be applied to mine closure planning in the following ways:

Annual LOM planning: Change is captured within mine planning cycles to review objectives, assess short- and long-term risks and implement management programs. Significant risks should be supported by an assessment of critical controls and reviewed by corporate governance, which may include independent technical review panels. Asset retirement obligation (ARO) estimates should reflect material changes onsite, highlight the assumptions used, and apply international financial reporting standards risk factors.

Unplanned LOM changes: Standards for risk management and project lifecycle that involve change management triggers (e.g., a CAPEX project greater than a specific dollar amount or technically challenging and uncertain projects) and a structured decision analysis approach help maintain focus and continuity in assessing the effects of change on the business and integrating these into annual business and closure planning.

Formalized LOM closure planning: This process, typically conducted every four to five years, involves meaningful engagement with stakeholders on closure objectives (e.g., end land use), analysis of risks and opportunities, revising a closure design basis, developing closure alternatives and design criteria, and establishing programs with quantitative performance and success criteria developed to demonstrate how closure objectives are achieved.

The figure above (adapted from the ICMM Planning for Integrated Mine Closure toolkit) represents a useful guide to integrate the above processes into decision making.

Mine closure risk and opportunity assessments are crucial to mine management and should be evaluated independent of day-to-day operational risks, as these can carry a much longer likelihood return period. Meaningful collaboration with stakeholders in identifying a positive land use legacy is critical and complementary to determining the range of residual risk tolerance. This will vary for each site but can be categorized as:

•Tolerable, where the site can demonstrate evidence of a safe, stable, non-polluting landscape;

•Intolerable, where effects can be practically reduced to a tolerable level through a range of preventative controls; or,

•Intolerable, where effects may result in long-term legacy issues or active care and maintenance.

A great deal of effort should not be required to better manage and track legacy risks in the resources industry. When an initial closure plan is technically flawed and lacks stakeholder buy-in or when the requirements to achieve an approved, beneficial plan are not adapted well during operations, mine closure can be very costly in terms of cash, reputation and long-term liability. The “conceptual ideal” level of mine closure design during initial permitting should be changed to a “pre-feasibility” level that is supported with design and costs at about 30 per cent accuracy. The closure design basis and supporting studies, design and LOM ARO cash flows can then be optimized and advanced to “feasibility” level project definition during operations.

Mine closure needs to be recognized during operations as a business risk and as a defined LOM change. Hopefully, an integrated LOM approach to change management can be adopted and improved on by practitioners, with concern for local issues and mine project definition stages.

Plan-Do-Check-Act Framework

PLAN: Establish a sense of urgency, define vision and objectives, gain consensus and readiness for change, define roles/responsibilities, and assess positive/negative risk through structure decision analysis.

DO: Execute the plan with required skills, incentives and resources, while removing inefficiencies.

CHECK: Review implementation/effectiveness with project and review teams, inform and align stakeholders, and communicate short-term wins and lessons learned.

ACT: Review vision, objectives, and action plans as part of annual and long-term business planning cycles. Sustain change as part of corporate culture.

Jonathan Sanders is a senior environmental scientist at Klohn Crippen Berger.

Matt Wendtman is a health and safety coordinator at Glencore Coal.

Alex Sexton is a health, safety and environment business partner at Glencore Copper.