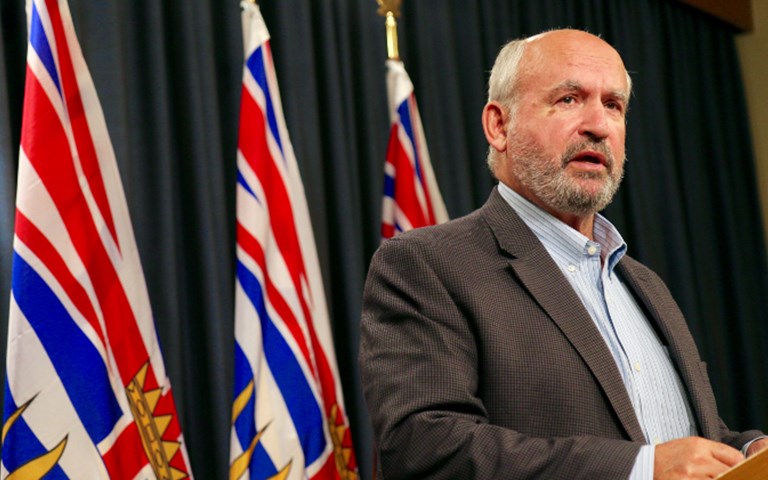

Bill Bennett, British Columbia’s mines minister, announced the province’s amended mining code in July, which improved tailings dam safety and oversight in the wake of the 2014 Mount Polley spill. Courtesy of the Government of British Columbia

Although 2016 continued to be a tough year for the mining industry, legal changes were not generally among its greatest challenges. Most provincial and national governments took steps to encourage mining activity with lower taxes or more favourable laws. Other jurisdictions focused on environmental protection or social uplift, with more mixed receptions from industry.

In Bolivia, conflict deepened between President Evo Morales’ administration and the subsector of self-managed, minimally taxed and regulated mining groups known as cooperatives. During August protests over the government’s perceived unhelpfulness in a difficult economic climate, several miners were killed by police and a deputy minister was kidnapped and beaten to death by protesters. Morales responded by imposing further controls. Cooperatives must distribute profit equally among members; anyone working for a cooperative has the right to unionize and receive benefits; and inactive mining concessions and joint ventures with private companies revert to the state. “The cooperatives have had it pretty easy compared to the rest of the sector,” said Arthur Dhont, senior analyst at IHS, a financial services company based in London, England. “Now that that relationship is damaged, the government is less likely to favour cooperatives over others in the sector in the future. For foreign mining firms, that should translate to greater opportunity to participate in mining projects.”

In several jurisdictions, mining lobbies successfully persuaded governments that lower taxation would be a win-win.

Zambia acceded to copper miners’ request for a price-based royalty rate. As of April 2016, a royalty rate of four per cent applies when copper prices are below US$4,500 per tonne, six per cent at prices above US$6,000 per tonne, and five per cent in the range between these price triggers. Royalty rates for other base metals were fixed at five per cent and precious metals and gems were set at six per cent. Zambia’s parliament also removed a variable profit tax and suspended a 10 per cent export duty on ores and concentrates that cannot be processed in Zambia.

Argentina’s new president, Mauricio Macri, lifted a five per cent export tax on mining products in February. According to Brent Bergeron, executive vice-president of corporate affairs and sustainability at Goldcorp, the new administration has started collaboration between ministries and put a strong emphasis on communicating transparently with mining companies. Bergeron sees potential for a new public-private financing law passed in November to benefit infrastructure projects at Goldcorp’s Cerro Negro mine and around the country. He also anticipates a taxation reform in the new year that could potentially link taxes to the price of gold. “They’re taking a look at the models in Chile and Peru so that they can make it more of a progressive taxation system,” he said.

Alberta concluded its oil and natural gas royalty review in January with a new regime intended to respond flexibly to industry conditions while growing revenues over time. Royalty rates in early production start at a flat five per cent per well, then, when the wells reach maturity, vary based on revenue minus costs. Aging wells will be subject to lower royalties. The new royalties apply to wells drilled in 2017 and later; existing royalties will still apply to older wells for 10 years. The royalty system for oil sands will remain unchanged. Economists Daria Crisan and Jack Mintz calculated in October that the new regime would lower taxation rates overall and make Alberta more competitive.

Canada’s 2016 budget made development expenses fully deductible in the year incurred and extended the mineral exploration tax credit another year to March 2017.

A few jurisdictions completely renovated their mining legislation – or created new categories from scratch.

In a bid to encourage mining, Kenya replaced its 1940 Mining Act with updated legislation in May. The act creates an online licence application process, a state mining corporation, and a minerals and metals commodity exchange. It applies different terms to large- and small-scale operations and allows corporations to have prospecting rights, which were previously limited to individuals. Work is now underway to develop corresponding regulations. Previously-issued mineral rights will continue under existing terms and conditions. “This provision sends a strong message that Kenya is serious about investment stability and security of tenure,” said Tim Carstens, managing director of Base Resources, which operates the Kwale mineral sands project. He said another important provision shares royalty revenue with the county and community levels of government where mineral extraction takes place.

Nova Scotia also overhauled its Mineral Resources Act in May. The new act extends exploration licences to two years, up from one; extends the deadline for starting production on a lease to five years (previously two); requires a reclamation plan and stakeholder engagement plan; and makes royalty rates easier to adjust by moving them out of the act and into regulations. “We have had extensive discussions with the government about the regulations and we are pleased with the direction the government is taking,” said Sean Kirby, executive director of the Mining Association of Nova Scotia.

Luxembourg passed a law in November regulating space resource exploration and guaranteeing that private companies exploring near-earth objects can keep resources they discover as long as they obey international law and receive authorization for their work. The government also invested €25 million in U.S.-based Planetary Resources as part of an asteroid mining initiative intended to go prospecting by 2020.

Black empowerment motivated proposed reforms in Africa.

The Ministry of Mines and Energy in Namibia added terms and conditions for new and renewed licences. Among other requirements, the licence holder must be five per cent owned by Namibian entities and at least 50 per cent of its management must be “previously disadvantaged Namibians” (that is, not able-bodied white men). Brandon Munro, chief executive officer of Bannerman Resources, which has a uranium project in the country, said the requirements are drawn from a voluntary Mining Charter implemented by the Chamber of Mines in 2014 and are therefore uncontroversial. The move is part of a broader poverty-eradication effort; draft legislation released by the Prime Minister’s office in February would promote participation by disadvantaged Namibians across industries. The bill is targeted for spring 2017 passage after a long public consultation process.

In South Africa, efforts by the Department of Mineral Resources to incorporate new black empowerment measures into the Mining Charter continued to encounter opposition from the South African Chamber of Mines, which criticized a draft released in April for imposing additional tax burdens, raising procurement targets for black-owned businesses and requiring miners and suppliers to pay into a Mining Transformation and Development Agency. “We have explained that this will take away critical funding for skills programs and tertiary and community education currently undertaken by the companies, and will place these funds directly with a new government agency whose mandate and governance structure has not been rationalized or explained to the industry,” said Memory Johnstone, spokesperson for the Chamber of Mines. The draft retains a provision proposed in 2015 – which is potentially being challenged in court – that would require mining projects not only to start off with 26 per cent black ownership, but also to maintain that minimum continuously.

Environmental concerns drove actions elsewhere.

In Canada, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced in October plans for a nationwide carbon pricing benchmark to be put in place by 2018, with implementation delegated to provinces and territories. British Columbia amended its mining code in July to improve tailings dam safety and oversight in the wake of the 2014 Mount Polley spill to positive industry reception.

The Department of Energy and Natural Resources of the Philippines suspended 10 of the country’s 40 metal mines and recommended the suspension of 20 more. Newly elected president Rodrigo Duterte and Regina Lopez, his appointee for Environment and Natural Resources Secretary, have indicated a tough approach to pursuing high environmental standards. Lopez has said she wishes to continue a now four-year moratorium on new projects.