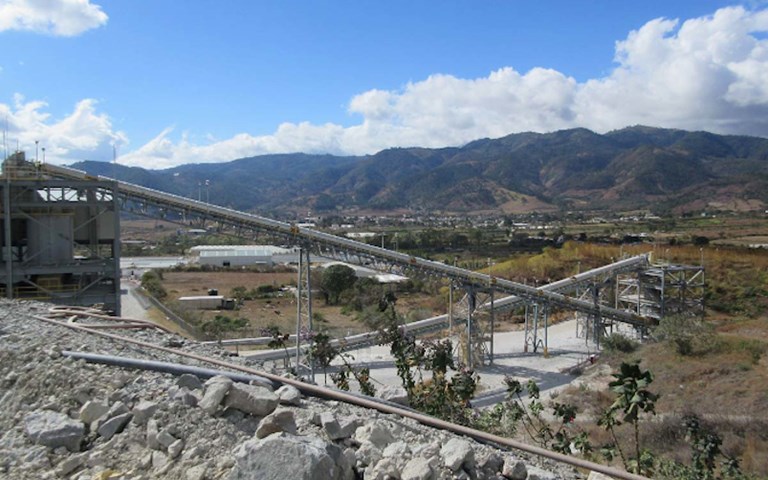

Pan American Silver settled a six-year legal battle in 2019 regarding a shooting at Tahoe Resources’ Escobal silver mine in Guatemala. Courtesy of JDS Energy and Mining

The federal office aimed at addressing potential human rights abuses by mining, oil and gas and garment sector companies operating abroad is expected to start taking complaints in the first quarter after multiple delays, but some non-governmental organizations and human rights experts are already calling the role a disappointment.

Announced by the Liberal government in January 2018, the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise (CORE) was launched to address calls from non-government organizations, human rights experts and four United Nations bodies for greater oversight of Canadian companies operating abroad. The role was envisioned as an independent watchdog with the power to investigate allegations; recommend remedies such as compensation, apologies and changes to company policies; and oversee their implementation.

While public stakeholders initially hailed the role, the ombudsperson’s promised investigatory powers have become a source of contention. In July 2019, all 14 civil and labour union representatives on the panel advising Ottawa on how the CORE should work resigned in protest, citing an erosion of trust in the federal government’s willingness to imbue the office with commissioner-like powers to compel documents and witness testimony.

Responding to concerns about the role’s effectiveness, ombudsperson Sheri Meyerhoffer told CIM Magazine that the CORE was committed to promoting human rights and “making a positive difference in the world,” and had “a range of tools at our disposal to help make that happen.”

Advocates and Meyerhoffer herself have called on the federal government to give the office those powers, but to date it has not done so. Meyerhoffer said her current focus is on “creating and launching an independent and impartial office that will deliver on its mandate to strengthen responsible conduct by Canadian companies abroad.”

A report on the CORE’s “listening tour” with various stakeholders said civil society organizations, Indigenous experts in Canada and abroad and other groups were concerned that without that level of power, the office would not be able to effectively fulfil its mandate. Meanwhile, industry stakeholders preferred “voluntary, industry-led approaches to encourage respect for human rights” and dialogue and mediation to resolve disputes. They expressed concern that if the CORE could compel evidence, sensitive company information would not be protected.

Related: Why Canadian mining companies must measure and address human rights impacts early in a project

Ben Chalmers, senior vice-president at the Mining Association of Canada, said the association has practical concerns about how powers to compel could be used in an international context. “Should the government go down this route, we might understand how those powers could be exercised on a Canadian mining head office in Canada, or on Canadian citizens working abroad, but these are complicated issues that often involve third parties, police forces [and] security forces, and the question becomes how does a Canadian official exercise jurisdiction in those countries to try to get the full understanding?”

But Shin Imai, professor emeritus at the Osgoode School of Law and a director of the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project (JCAP), said investigatory powers are necessary to ensure affected communities are able to access justice for issues that may be too challenging to bring to court.

“There are a lot of situations where people may be removed from their land forcibly or there’s no prior consultation with Indigenous people,” he said. “Those issues would be very difficult to bring to the courts, and I think a properly funded ombudsperson with powers could investigate those things and…there could be clearer findings.”

He also pointed to the scale of harm abroad, highlighting a 2017 report from JCAP that found more than 400 people were harmed and more than 40 died – 30 in targeted killings – in connection with Canadian mining projects in Latin America. Hudbay Minerals, Tahoe Resources and Nevsun Resources have faced lawsuits in Canadian courts alleging various human rights abuses at their operations overseas, including shootings, assault, slavery and gang rape.

“I think when you’re dealing with crimes like this you need to be able to investigate,” Imai said, noting that bringing cases to Canadian courts can be too costly for communities, even if that venue has powers to compel.

But David Clarry, vice-president of corporate social responsibility at Hudbay, disagreed that those types of cases were the responsibility of the CORE. “I will note Hudbay is party to a litigation in Canada stemming from accusations related to a project we owned in Guatemala between 2008 and 2011. Our situation is an example of more complex, serious and strongly contested allegations that should remain the purview of a court to decide,” he wrote in an email to CIM Magazine.

The CORE has the ability to recommend that disputes be referred to law enforcement or regulatory authorities if the office has reason to believe a criminal offence or regulatory violation has been committed.

According to the CORE’s draft operating procedures, published in September 2020, the office can initiate reviews on its own or based on complaints. Both mediation and “joint fact-finding” are available during the CORE’s dispute resolution process if both parties consent, but the office can also conduct independent fact-finding if one or both parties do not agree to a joint process. At the end of the review process, the CORE can recommend remedies or changes to company policies and can even recommend withdrawing trade advocacy support and Export Development Canada funding for any companies that do not play ball.

Imai compared the office’s joint fact-finding process to investigating a crime, but only with the perpetrator’s co-operation. “The [company] you’re supposed to investigate is deciding all the way what to give you, and [is] there all the way while you look at and analyze information,” he said.

Chalmers, on the other hand, said the office’s mandate for collaborative dispute resolution is valuable. “One of the common misconceptions is that it’s really just mediation. It’s not. It is a form of investigation and the idea here is that you use that dispute resolution to start rebuilding trust and bridges,” he said, adding that instances of serious harm are better suited to a court. “It lays the foundation for both sides to better buy into the results when the results are complete. These are situations where the mine and the community aren’t going anywhere, and it’s in everyone’s best interest to address the harm and move forward.”