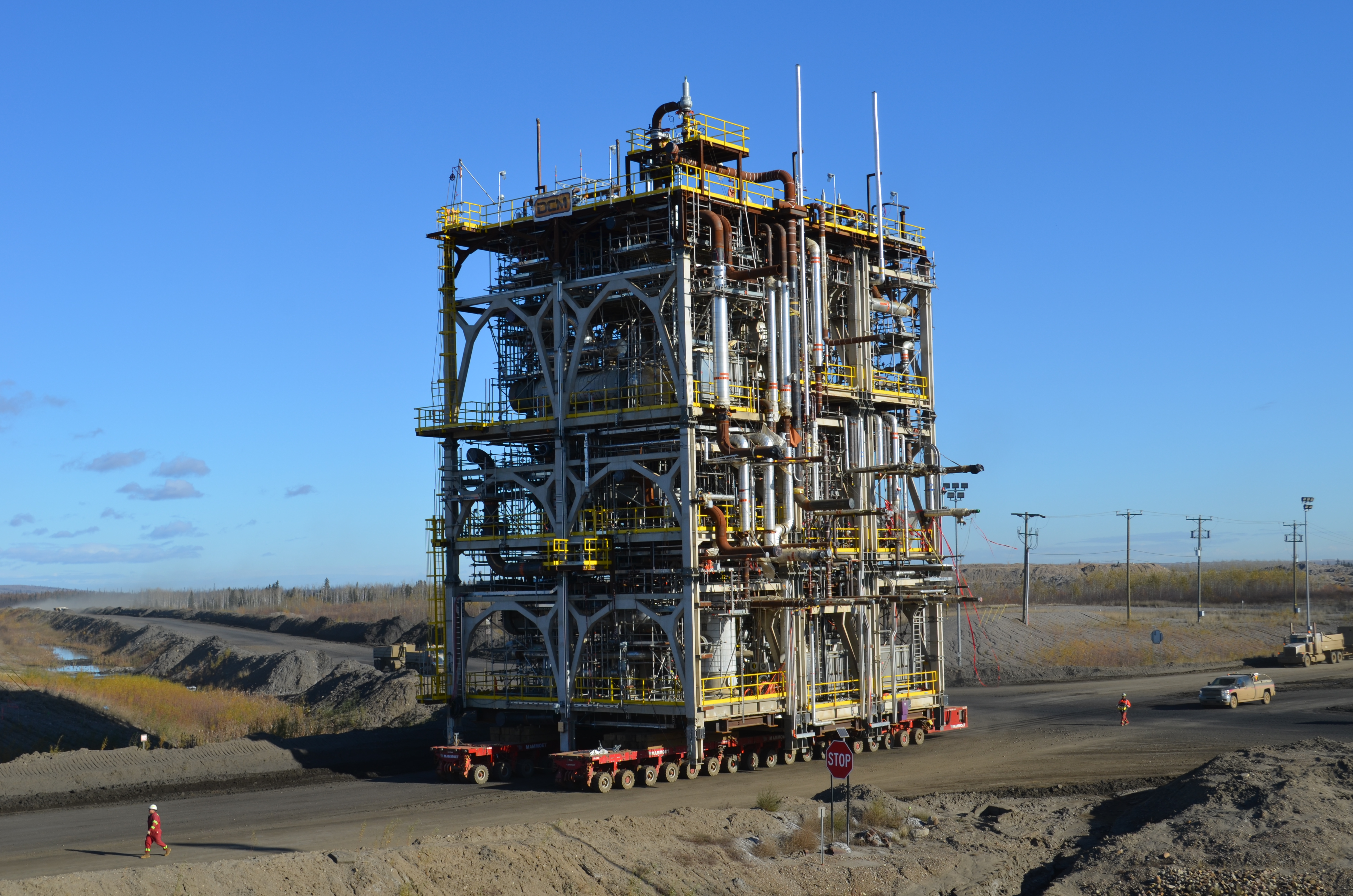

Logistics companies, like Mammoet, play a vital role in getting pre-assembled modules to site. Courtesy of Mammoet

As 2016 came to a close, Barkerville Gold Mines was partway through the installation of a 200-tonne-per-hour ore sorting plant at its Bonanza Ledge mine in British Columbia. Tom Obradovich, director and consultant at Barkerville, estimated that the on-site construction process – from delivery to commissioning – would take about five weeks total.

Such a short timeline is possible only because the project is extensively modularized: pre-assembled off site and transported whole or in partially completed modules to reduce time spent on construction at site. There are any number of reasons this approach might make sense for a given project – so many that engineering companies now routinely evaluate it during early planning. The practice of modularization is continually expanding to include new types of equipment, more strategic planning and higher degrees of pre-assembly.

Mobility

For Barkerville’s 500-tonne-per-day mine plan, the modular approach sped up a construction process that would otherwise have taken four months at twice the cost. Steinert Global pre-assembled the ore sorter, which is fitted wheels for easy movement, in Germany and then shipped it in three parts to the site, where German technicians reassembled it inside a prefabricated structure and over a minimalist concrete and gravel foundation.

The ability to move is key for what Obradovich has in mind for the ore sorter, which is destined to separate potentially acid-generating piles of waste into gold-bearing sulfides. “We have historic mines across a six-kilometre area, with waste piles spread out over that whole length of property,” said Obradovich. “There are several hundred thousand tonnes of material that may be amenable to ore sorting. If we are successful in developing the technology, or we find other areas that are amenable to ore sorting, we can simply move it to a new project.”

Plug and play

Barkerville worked with engineering firm Sacré-Davey, whose consultants encourage clients to consider this kind of “plug and play” modularization. “If you have a small plant, you don’t have to go with a traditional design,” said Brent Hilscher, principal engineer at Sacré-Davey. “You can have a skid-mounted ball mill or skid-mounted crushers. It can cut your capital in half. And everything really is plug and play. So you plug in your ball mill, and you plug in the piping to it, and your ball mill is done.”

Sacré-Davey has done a few such installations. According to Hilscher, there are hundreds of others around the world. A typical site would be a high-grade underground gold operation running at 50 to 100 tonnes per hour. Structures that are small enough do not require foundations or heavy-duty cranes; for milling and leaching, for example, that would allow a throughput of less than 100 tonnes per hour. A pre-crushing system could go up to 1,000 tonnes per hour.

The range and availability of different types of plug and play equipment is growing. In 2016, Outotec introduced a modular water treatment plant with an advertised per-unit throughput of between five and 40 cubic metres per hour.

These small systems can be scaled up by running them in parallel. Hilscher said that while many mine operators are comfortable running a couple of small ball mills in parallel, the concept of a three-mill circuit consistently hits a psychological barrier, even though it could still save on capital cost. “In that case we just design them a traditional circuit with a single ball mill.”

One final benefit to plug and play systems emerges at the end of their use: The resale value of modular equipment vastly exceeds the value of fixed equipment. Hilscher said he recommends that his own clients buy new, but they can look forward to a thriving secondhand market.

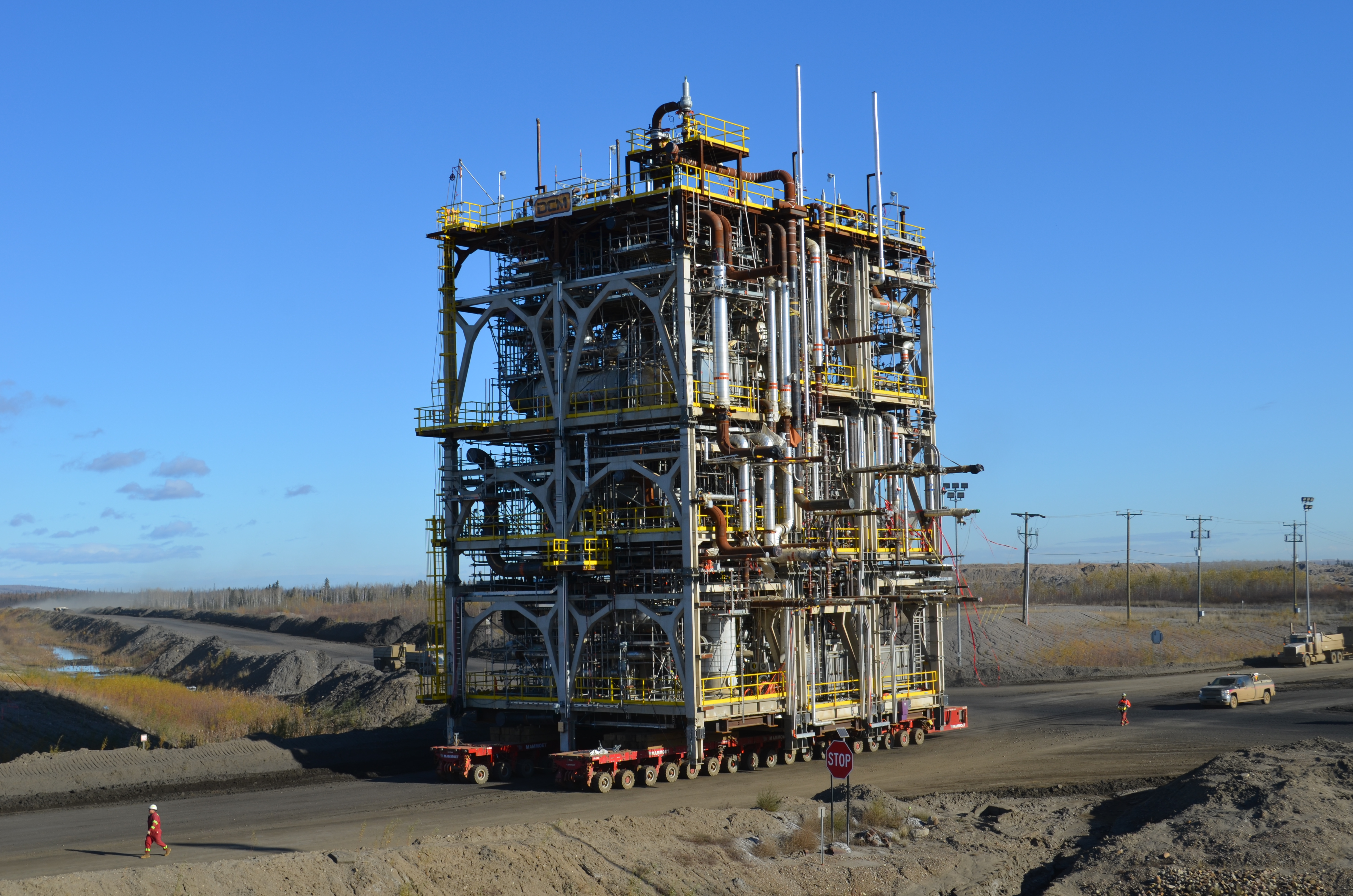

Fluor’s 3rd Gen modular approach at Shell’s Quest Carbon Capture and Storage project in Alberta helped the company save plot space and reduce costs. Courtesy of Fluor

Fluor’s 3rd Gen modular approach at Shell’s Quest Carbon Capture and Storage project in Alberta helped the company save plot space and reduce costs. Courtesy of FluorDesigning modular facilities

Although high-volume ball mills might not be ready for plug-and-play design, large operations can still benefit from the trend toward packing more components into a single module. In the last several years, EPCM giant Fluor updated its execution method to address its clients’ need for greater capital efficiency. The result is what Fluor calls 3rd Gen Modular Execution. “It’s an approach to modularization that challenges traditional design methods by having the module strategy drive the layout of facilities, rather than vice versa,” said Tony Morgan, vice-president of global business development and sales for the mining and metals division at Fluor.

The approach groups together items of equipment involved in the same process. “For example, if you needed to pump hot liquid from a vessel and cool it, a logical process block would be the vessel, pump, heat exchanger and all associated instrumentation,” said Morgan. “This approach increases the portion of a facility that can be modularized by consolidating equipment and components into the modules.”

Because so much of the facility is modularized – including piping and electrical systems – Morgan said that these site-assembled modules were essentially plug and play, similar to the pre-assembled equipment. All the cabling, wiring and testing is completed in one of Fluor’s four module assembly yards, in the same way that pre-assembled crushers or ore sorters are given a test run before shipping out.

At Shell’s Quest Carbon Capture and Storage project in Alberta, Fluor’s 3rd Gen approach reduced the plot space requirements by 20 per cent from initial estimates and delivered the project at 30 per cent below the initial estimated cost. “These results are typical,” said Morgan. “When we examined using this approach on the grinding and flotation areas of a copper concentrator, we saw a 10 per cent reduction in the project footprint and over 10 per cent reduction in the capital cost.”

The Alberta oil sands operations were early and committed adopters of modularization. In Alberta, high labour costs are the main driver – although there are other considerations as well.

“We have some very vertical plants at Fort Hills,” said Ron Genereux, vice-president of productivity and construction at Suncor Energy. Assembling modules on the ground in yards in the Edmonton area and then using a crane to stack them on site is safer than having construction workers up on tall scaffolding during the entire construction period. Ironworkers do need to go up to bolt the modules together, but a crew of eight to 10 people can set three to five modules in a day. Traditional construction would take weeks or months to make the same progress.

“We’ve been pleasantly surprised by the ingenuity of what engineers can put onto the modules,” said Genereux. “They’ve been able to come up with some unique and innovative designs on making heat tracing more efficient and effective, such that we can do essentially all of the work in the module yard, test it out, verify that it operates and it controls properly before we even ship the module, which takes a lot of man-hours out of the field for quality assurance and testing.”

Assembling at ground level cuts down on the cost of scaffolding and the travel time to get up high; it improves the quality of construction; and, of course, it substantially reduces the cost of transporting and housing workers.

In light of these benefits, the price of shipping larger and more complicated loads fades in importance. “The cost to transport a module from Edmonton up to Fort McMurray is in the range of $15,000 to $20,000,” said Genereux. “If you can save yourself a hundred man-hours, you’d probably pay for it.”

Site-specific solutions

Modularization by itself does not always cut the estimated cost of a project. It does, however, significantly lower the cost of working in places like Alberta and Australia, where labour is very expensive and modular approaches are typical on mining projects. Fluor also used extensive modularization on a BHP Billiton iron ore expansion project in Western Australia, for example.

In some cases, though, transportation demands pose too large a challenge. “Obviously copper projects 4,000 metres up the side of a mountain in the Andes have different logistical challenges to projects with coastal access,” said Morgan.

Hilscher judged that introducing modularization might be a break-even proposition at Mexico’s comparatively low-wage rates. The reason an operation might choose to do it anyway: modularization lowers risk.

“A lot of the risk in a project is on-site labour risk,” said Hilscher. “How long is it going to take to build? And how many unforeseen problems are there going to be? If you send the whole thing up in 10 or 20 modules and bolt them together, it cuts that risk dramatically.”

The appeal of that concept is evident in the bid requests companies are putting out. René Bernaert, co-founder and director of engineering at the modular structure company Corner Cast, said that he has seen an increasing number of engineering firms tailor their specifications to the unique requirements of modular buildings. “More and more, we are asked in the early stages to modularize the client’s design, to create a cost-effective, prefabricated solution for their project,” he said. That is a very welcome contrast to more typical requests, in which Corner Cast is given a recycled conventional design and asked to come up with a modular solution using the same parameters. “It is difficult to redesign and optimize a building in the final stages of the procurement process.”

Moreover, prefabrication itself is becoming more customized, according to Bernaert. “Client requests traditionally were more focused on trailers, camps and simple layouts,” he said. “Now we see clients requesting more customized buildings like water filtration facilities, garages and a variety of different modular complexes.”

A pre-assembled ore sorter is key to Barkerville Gold Mines’ project to separate potentially acid-generating piles of waste into gold-bearing sulfides at its Bonanza Ledge mine in British Columbia. Courtesy of Sacré-Davey

A pre-assembled ore sorter is key to Barkerville Gold Mines’ project to separate potentially acid-generating piles of waste into gold-bearing sulfides at its Bonanza Ledge mine in British Columbia. Courtesy of Sacré-DaveyPlanning and logistics

Since modularization hinges on creative uses of space and transportation, logistics companies have a particularly important role to play in making it work. Gavin Kerr, account manager and a leader in sustainability and innovation at Mammoet Canada Western Ltd., pointed out that logistics extends well beyond delivery. How flexible the delivery sequence can be, for example, will depend on whether the modules are set using a crane or a specialized transporter, and that in turn depends on how much space is available, what ground preparation costs it can assume, and so on.

Early planning determines whether the delivery will come off successfully at all. Although lots of mining operations are able to benefit from approaches originally developed in offshore oil and gas, Kerr cautioned against thinking that will always work. “I can’t stress enough how important it is to engage really early with as many stakeholders as possible during those early-stage concept and preliminary designs of the plant to make sure that what you’re putting on paper can indeed be achieved.”

Public consultation can also play a key role. Imperial Oil learned that lesson the hard way when modules assembled in South Korea and destined for its Kearl oil sands mine were held up on the intended transport route through Idaho and Montana. Stakeholders along the route successfully blocked those planned megaloads from using a local highway, and ultimately each of the modules had to be divided in half and shipped via an alternate route at an additional cost of $100 million.

Given that the modular design and construction approach was born in the offshore oil and gas sector and took its first steps not far from the tideline, its application at remote, seasonally challenging or labour-competitive inland operations is demanding a further evolution.

Mammoet has found a number of ways to lift, ship and set ever heavier and more complex modules. For example, Kerr is participating in an oil sands industry proposal to permit denser modules in Alberta. There are strict guidelines on module dimensions and permitted axle loadings on public roads. The proposal would increase the number of tires per axle line on a trailer so that modules of the same size, by maintaining the same pavement loading per tire, could nonetheless be heavier.

“The only thing that changes is the density of the module,” said Kerr. “So it allows the designers and the constructers to put more man-hours and more equipment into the module before it arrives on site. By allowing a denser module, you provide owners with a huge opportunity to reduce their total install cost.”

Beyond new construction

In recent years, Mammoet has applied modularization to the problem of relocating existing facilities including at Syncrude’s Aurora mine and Teck’s Highland Valley Copper mine. At Aurora, the crusher, surge bin and slurry prep building ranged from 2,500 tonnes to 4,000 tonnes. “They were each moved in one complete building,” said Kerr. “It saves a huge amount of capital cost and it’s also in the interest of sustainability that you have much less waste.” He said he thinks there could be much more of this in the future, particularly if mine operators design their facilities for relocation right from the start.

On-site “super-module” transport, where smaller pieces of pre-assembled equipment are put together on site, allows companies to modularize while mitigating the headaches of long and cumbersome logistics chains, according to Mammoet’s Gavin Kerr. Courtesy of Mammoet

On-site “super-module” transport, where smaller pieces of pre-assembled equipment are put together on site, allows companies to modularize while mitigating the headaches of long and cumbersome logistics chains, according to Mammoet’s Gavin Kerr. Courtesy of MammoetWhen not to modularize

Despite the success stories, Kerr said he thinks there can be a temptation to overapply the practice.

Trying to transport rotating equipment or very light preassembled equipment may be more trouble than it is worth. “A steel shell with some pipe on it for example,” Kerr said. “Because it’s so light, it doesn’t have any rigidity, so in order to make it feasible for it to be transported and then lifted into place on the foundations at site, you have to add in a whole bunch of temporary steel to make it stiffer.”

Financial pressure

In the present rough financial climate, however, some companies are finding that a modular strategy can save projects that would otherwise have to be scrapped due to the high cost of construction.

“Mining changes when it has to change,” said Sacré-Davey’s Hilscher. “And over the last couple years, it had to change.”

The situation has made 2016 an interesting year for Corner Cast. “We are experiencing increased demand and we’re delivering more projects than ever before,” said co-founder Magnus Consiglio. “You’re seeing bids come out that are specifically asking for these types of modular buildings. […] But at the same time, we found that because of the underlying commodity prices, a lot of projects are on hold and waiting to see light in 2017.”

Still, he added, “The overall trend is extremely positive. All of the things that we’ve been promoting – the relocatable nature of the product, the low upfront cost, the lower operational cost and the fact that we can integrate so many functions into one structure – are being accepted by the industry. We’re extremely excited for commodity prices to rebound and for this concept to really take off over the next five years.”