The narrow, high-grade veins at the Macassa and South Mine Complex have been mined since 1933. The emphasis at the mine is now ore quality over quantity | Katelyn Malo

Erratic gold prices have affected every gold miner. As prices peaked above US$1,800 per ounce as recently as two and a half years ago, many companies invested heavily to expand their operations and take advantage of the historic highs. But when prices plunged to their more recent levels – below US$1,300 an ounce – many of those same companies discovered that their newly expanded operations were no longer profitable. Kirkland Lake Gold was one of those companies. How the miner has turned itself around over the last year is a case study in re-examining basic assumptions in the business case and successfully implementing a wholesale culture change on the ground.

During the boom, Kirkland Lake raised nearly $100 million for investment in the infrastructure at its Macassa and South Mine Complex in Kirkland Lake, Ontario. An upgraded hoisting system, new battery-powered underground mobile equipment, and a refurbished mill – including a new 15-by-20-foot Sanland primary ball mill to supplement three existing Allis Chalmers mills – helped push capacity up to 2,200 tons per day from 1,400 tons per day with recovery rates of 96 per cent. The aim was to produce 200,000 ounces annually. At the same time, the labour force grew to 1,250 workers by late-2013 from 200 employees five years ago. Like many gold mining companies at the time, Kirkland Lake was building itself to push tons.

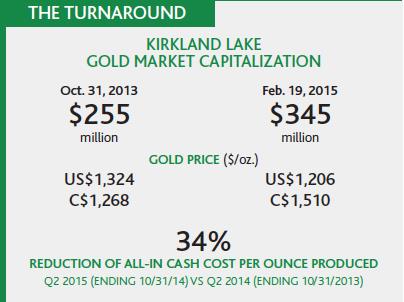

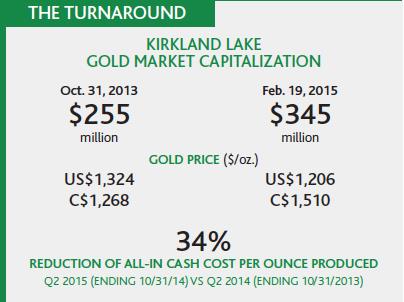

“Two or three years ago, Kirkland Lake had a market capitalization of $1.5 billion,” says current CEO George Ogilvie. Like many miners, Kirkland Lake used the high gold price to lower its cut-off grade. The company began mining more marginal ore outside the high-grade veins that characterize the Macassa ore body.

The quality of the ore hoisted to the mill has gotten special attention.

The quality of the ore hoisted to the mill has gotten special attention.

Then the gold price started to dive. “Suddenly, pushing tons at the expense of the grade was not going to make money once the gold price dropped below US$1,500 to US$1,600 per ounce,” Ogilvie says. But with so much money invested in the plan to push throughput, Kirkland Lake attempted to stay the course. The company compounded its growing problems by setting goals to the market that it was unable to achieve. “They were over-promising and under-delivering, which was also affecting the share price,” Ogilvie says. Combined with the plummeting commodity price, its market capitalization collapsed to $150 million a year ago, spurring major changes at the mine.

Ogilvie was brought on in November 2013 by then Kirkland Lake chairman Harry Dobson. He came from Rambler Metals in Newfoundland, where Dobson was also chairman. Ogilvie won Dobson’s confidence with his combination of experience in the ultra-deep gold mines of South Africa – a similar technical environment to Macassa – and with his success at bringing Rambler to production in the midst of the global financial crisis, during a notably difficult time for the mining industry.

Related: Kirkland Lake stays on top of seismic events at its Macassa mine

“Once I accepted the position, I already had a very good idea that to make the mine successful and make the company successful, we were going to have to get back to trying to mine closer to the reserve grade,” Ogilvie recalls. “It’s the one thing that differentiates Kirkland Lake from probably 99 per cent of the other gold mines in the world: the reserve grade. No matter what the gold price environment is, a core fundamental of our business has to be mining near or at the reserve grade at all times.”

In fact, when Barrick and then Kinross owned it during the ’90s, the mine regularly mined at more than 18 grams per tonne. Ogilvie says he believed that getting back to that philosophy could spell redemption for the floundering operation. By mining at the current reserve grade – estimated at 17 grams per tonne – the company ought to have the capacity to remain profitable even in difficult gold price environments. In a very high gold price environment, the company would be able to make a substantially higher margin and generate free cash flow very quickly.

But changing the philosophy of an entire company wasn’t going to be easy. “How do we change the culture from tons and quantity,” Ogilvie wondered, “and get people focused more on grade and quality?”

How to stop a ship from sinking

Concerns about the level of support that Ogilvie would experience from senior management, who remained from the previous regime, were quickly allayed. The team was committed to change. In fact, they had made many of the same recommendations that Ogilvie subsequently implemented. Among those changes, the number one priority had to be to get the head grade up, which meant reducing external dilution.

|

At the time Ogilvie came on, incremental ore was being mined as a matter of course, says Kirkland Lake spokesperson Suzette Ramcharan. Worse, other low-grade material, including waste, was finding its way into the ore pass. Whether due to workplace culture, the fact that the bonus system measured employees on tons and footage, or a combination of the two, waste in the ore pass was lowering the head grade and decreasing productivity. Management acted quickly, using an old method Ogilvie had picked up in South Africa. Supervisors put metal washers, stamped with a serial number and date, into the mine’s waste piles. As material entered the mill, magnets picked up the washers, betraying when and where waste material came from – and therefore which miner had directed it to the ore pass. Within six weeks, waste material stopped entering the ore pass. Head grades jumped to 0.43 ounces per ton in January 2014 from 0.29 ounces per ton in November 2013, an improvement of nearly 50 per cent.

In January 2014, the company was forced to cut 75 positions. Over the next year, attrition claimed another 160 employees who were not replaced. The net loss of those 235 employees, or roughly 20 per cent of the total labour force, has not hindered production.

Some skills did have to be supplemented, however. “This ore body is a very difficult ore body to read,” says Ogilvie, due to the narrow veins of high-grade ore. “You might think you’re mining on the vein or mining in the ore, but in reality you could be in the wall. It has to be very carefully monitored.” So additional underground geologists were hired to ensure every rock face could be inspected on every shift. The bolstered force now takes 30 per cent more chip samples than it used to, and geologists mark up lines on underground faces to direct miners where to continue mining in order to stay in the high-grade veins.

The mine’s assay lab also received a staffing boost so it could be active around the clock. Previously, the lab closed on nights and weekends, meaning an assay might not be turned around for up to 48 hours. With the newfound focus on grade, uncertainty about the ore quality was unacceptable. The assay lab now turns samples around in eight to 12 hours. “The next shift coming on knows exactly what is ore and what is waste, and where it has to be moved to,” explains Ogilvie.

Related: Goldcorp and Sandvik partner to deliver all-electric mine at Borden Lake

Another important factor in the company’s turnaround – which is evident in its more recent market capitalization of nearly $340 million – was raising the cut-off grade to 0.22 ounces per ton from 0.18 ounces per ton. By decreasing the amount of marginal ore that is mined, the company saves on labour, equipment and processing costs. The mine is now using only 1,100 tons of its 2,200-ton-per-day capacity, but the higher grade ore and lower labour costs mean that the company is once again profitable and with free cash flow, a step in the right direction.

Running the mill at half-capacity does create some inefficiencies, admits Ramcharan, due to the fixed costs of “keeping the lights on,” so to speak. During the summer, the mine was able to run the mill on a five days on/two days off schedule, stockpiling material over the weekend to process the next week. “But in the winter, you don’t want to shut down the mill, for fear of something freezing,” says Ramcharan. “So we’ve gone back to seven days per week for the winter, so we do have some cost savings that we’re not able to see because we’re not operating at full capacity.” Additional exploration could find new high-grade targets that might help bring production up, but that is a longer-term plan. For now, the focus is on managing the current changes.

There's more to a mine than just machines and a mill

These changes gave the company the technical capability to mine closer to the reserve grade it wanted again, but changing the culture meant more than just providing employees with better information and preventing them from taking advantage of the system.

After nine months of evaluating the mine, Ogilvie and his new vice-president of operations, Chris Stewart, brought in a consultant to perform leadership training. Ray Bushfield of Laidy and Ray Consulting was hired to help improve the leadership, management and communication skills of the senior, mid-tier and front-line supervisors. During the company’s growth to 1,250 employees from 200, most had never received training to teach them the skills necessary for their new roles managing much wider areas of responsibility. Now they were finally learning how to communicate with their employees, provide feedback and, where necessary, counsel employees on difficult subjects like lack of productivity or absenteeism.

In the spring of 2015 there were 1,015 workers employed at the mine.

In the spring of 2015 there were 1,015 workers employed at the mine.

Even more recently, in a move that mirrors the practices at Goldcorp’s high grade Red Lake operation, the bonus structure at Kirkland Lake was scrutinized with a thought to move the focus on ounces produced, rather than on footage and tons. Including components for safety and cost as well as productivity, the new bonus structure will be more in line with the company’s corporate objective to mine quality ounces.

The labour force itself, meanwhile, is still in flux as management tries to find the “sweet spot” where costs are minimized while production remains unaffected. Productivity is back up to the historical average at the site of one ton per day per worker, after dropping for a time below 0.9 tons per worker. Ogilvie says he believes, however, that the mine can produce 1,200 to 1,250 tons per day with the current labour force of 1,015 employees. He hopes to achieve that by the end of the mine’s fiscal year in April.

Related: New guideline aims to help equipment manufacturers standardize battery tech for EVs

Ramcharan notes that Kirkland Lake has budgeted costs for the 2015 fiscal year based on a gold price of $1,350. “We believe around $1,000 per ounce is a break-even point that we could sustain” with additional cost-cutting measures, she adds. With prices comfortably above that level for now, the company appears to be in good shape. Its gradually rising share price and return to profitability in the last two quarters bear that out. “Just because gold has come off $500 an ounce doesn’t mean this mine is going anywhere,” Ramcharan emphasizes.

Blessed with one of the highest-grade ore bodies in the world, Kirkland Lake has always had the ability to be a winner. With its new focus on profitability instead of pure production, the company is on a path to live up to its potential once again. For the 10,000 residents of the town of Kirkland Lake plus the surrounding communities that depend on the mine as an economic driver, that is the best news they have heard in a while.

Battery-powered mining

The Macassa and South Mine Complex is on the forefront of mining technology with some of the newest and most unique equipment in the industry. Faced with ventilation limits that prevented the mine from growing its underground diesel fleet, Kirkland Lake became one of the first companies in the industry to introduce battery-powered vehicles. A brand-new fleet of 12 load haul dump (LHD) scoops and three haul trucks, manufactured by RDH Mining Equipment, take long-life lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4) batteries, which produce no emissions.

The equipment enjoys flexibility that tethered electric machines and trolleys do not. The LHDs, with three-cubic-yard buckets, use batteries that can put out 100 kilowatts (134 hp), while the mine’s 20-ton haul trucks are outfitted with 165 kW (221 hp) versions. Both sets of batteries are made from common components and use the same software and controls, minimizing spares inventory, says company CEO George Ogilvie.

Of course, managing the batteries does require coordination as they must be swapped twice per shift. To ensure no downtime, one battery always has to be charging, one cooling, and one on the equipment. The company still uses diesel LHDs, but it will continue replacing diesel machines with battery technology moving forward.

One of 12 new battery-powered LHDs. Courtesy of Kirkland Lake Gold

One of 12 new battery-powered LHDs. Courtesy of Kirkland Lake Gold