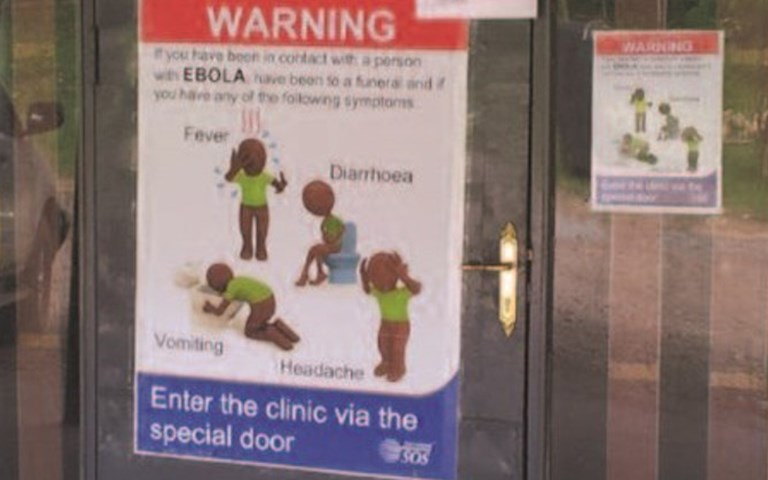

International SOS has set up emergency clinics similar to this one in Liberia throughout West Africa | Courtesy of International SOS

Ebola is a nasty virus – some victims suffer both internal and external bleeding – and with a death rate approaching 90 per cent, it is difficult to imagine a worse scenario for a remote mining camp than a possible outbreak. But that threat is real for companies operating in Africa, and particularly in West Africa. In late-March, the virus broke out in southern Guinea, quickly spread to the north, and by May had crossed into Liberia and Sierra Leone, where several people who fell victim to the disease in Guinea were buried. More than 200 people have died.

Dr. Sajjad Ahmed Gill followed the crisis closely. As group health advisor for Tullow Oil, a British oil and gas exploration and production company that operates throughout West Africa, it is his job to protect the company’s people and operations from such outbreaks. In this instance, it meant constantly monitoring the surrounding countries, and communicating with staff and a network of industry and health organizations. “There were lots of rumours and it was a big challenge to extract accurate information,” he recalls.

Plan for the worst

“West Africa has a unique pool of diseases that are not usually present in other parts of the world,” says Gill. “Any company working in such areas should be well aware about the risk of such diseases around them and should have a robust emergency management system to manage disease outbreaks.”

A disease prevention strategy and a health emergency response plan are the first lines of defence. An outbreak can have a devastating effect on operations, says Gill, but a solid plan can minimize this risk and allow a company not only to respond quickly and effectively to an outbreak but play a proactive role in controlling the spread of the virus as well.

Getting to this point takes a lot of work and often requires assistance from medical emergency management experts. Tullow Oil sought the services of International SOS (ISOS), the world’s largest integrated medical and security assistance company. “We have medical and security responses for any level of issue,” explains Doug Quarry, medical director at ISOS. “We also provide medical staff and often the facility itself to assist companies in their ventures and adventures around the world, everything from having medics on oil rigs to running full-sized, 40-bed hospitals.” For Tullow, ISOS helped make travel planning decisions and provided advice, but it did not arrange field clinics.

“Not every operation will require the same facilities,” says Gill. “Some locations may have well-equipped clinics while other locations may only have first aiders. It all depends on various factors, such as the number of people on site, the chances of injuries or illnesses, the distance to reliable health facilities and the availability of medical emergency support in the area.”

The remoteness, duration and extent of an operation all help determine its overall health risks. Other factors include the local environment, wildlife, and endemic diseases, and any activities that could increase the risk of exposure to diseases and infected wildlife. These include land development, hunting of wild game, poor waste management and food storage, as well as the lack of sanitation and potable water in the local communities.

Know what you are up against

Health risk assessment begins before any project development and continues through construction, production and reclamation activities. “We will visit the site, and look at the endemic diseases and the quality of the medical services in the area,” says Quarry. “Then we give the client a realistic set of suggestions as to what sort of medical services they might need around the site, and what sort of training or support the national employees might need.”

The Ebola virus is particularly contagious and lethal; the current strain is the most severe, with a 70 to 90 per cent death rate. There is no vaccine and no known cure. The virus is likely carried by bats, and humans are infected after hunting and eating an infected bat or another wild animal that the bat has infected. It then spreads between humans through contact with infected body fluids. An outbreak can be difficult to identify, as the early symptoms resemble other less-dangerous fevers. It can also be difficult to track, with a relatively lengthy incubation period of up to 21 days.

The best defence is often a good offence, and public health measures and support for local health facilities are some of the most effective areas on which to focus resources. “In most developing countries, the local health facilities are quite limited and the local health system needs external support,” says Gill. Companies like ISOS can provide assistance through malaria-control and vaccination programs and public health education services, which are important for a virus like Ebola, since people in remote communities often know very little about how it spreads.

Safety at odds with tradition

Some West African customs pose a major challenge to mitigating the spread of Ebola: according to traditional funeral rites, the dead body is washed prior to burial. So ISOS developed a series of educational materials for its client companies, which distribute these to the general public and use them to educate and train their own staff. “Education is a big part of the management of this disease,” says Quarry. “Training is so important.”

The risk to foreign workers is generally low, says Quarry: “Ebola is spread by direct contact with infected body fluids, and that is really more likely when you’ve got a sick family member, when you’re living in the same house and caring for them. The main risk is really to the local, national folk, and much less for expatriates and business travellers.”

Still, companies must be prepared to act if the disease poses a risk to their operations. “The response depends on the level of risk,” explains Gill. “It ranges from restriction of travel, to the evacuation of staff and closure of operations. The operational personnel may be reduced in number, the workforce from certain areas may be monitored and operations may be stopped for a short or long term.”

Tullow made important business decisions for staff safety. Operations were quickly modified to minimize the exposure of Tullow staff at all levels. At the same time Tullow contributed with other international health organizations to public medical treatment.

Similar work is being done by ArcelorMittal, which operates an iron ore mine in Liberia, just across the border from the most affected area in southern Guinea. ArcelorMittal has worked with ISOS to set up an on-site clinic. “When the crisis started, we realized very early there was a big risk for this clinic because it really is the best clinic in the area,” says Quarry. “The medical services in that area are pretty poor, so it was quite likely that if there were cases, that they would come to our clinic. But it’s not set up to be a public health facility, or a general hospital.”

ISOS brought in educational material, and ArcelorMittal relied on them to train its national staff. An isolation unit was set up at the mine clinic, and personal protective equipment was brought in for clinic staff and staff at the nearest local hospital – health care workers are some of the most at-risk of exposure. Most importantly, says Quarry, they also brought in a senior infectious diseases doctor from South Africa, who supervised the modification of the clinic and the training of its health staff. He travelled to other national hospitals to help establish isolation units and train staff on the use of personal protective equipment and infectious disease spread, and worked with Guinea’s Department of Health to set up the Ebola containment strategy.