The Yukon government announced two staking bans in late January, to the traditional territory of the Ross River Dena Council and to the adjacent territory, claimed by the Liard and Kaska Dena Council. Terry Feuerborn/Flickr

A rift between First Nations groups and the Yukon government has shut down a major swath of the territory to prospecting.

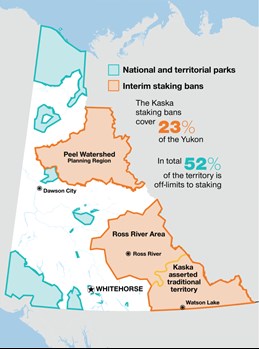

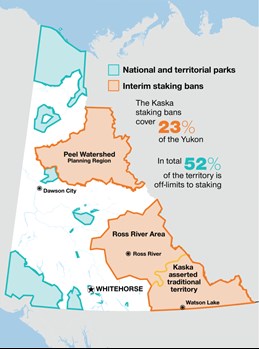

At the end of January, the Yukon government announced two staking bans on Kaska territory, a vast area that covers the south eastern corner of the Yukon and extends into British Columbia and the Northwest Territories.

The first is a year-long extension of a moratorium that covers the traditional territory of the Ross River Dena Council, who claim a 63,000-square-kilometre parcel of land. The second – which is set to expire at the end of April – covers territory claimed by the Liard and Kaska Dena Council, whose land sit adjacent to the Ross River territory and encompasses the Watson Lake mining district. The bans only cover exploration and do not affect current projects.

The land rights battle stems back to a 2012 Yukon provincial court case brought by the Ross River Dena Council – one of three Yukon First Nations who have never signed a treaty with the Yukon government. The decision obliges the government to “consult and accommodate” the First Nation when it comes to mineral exploration on its traditional territory. (Following the decision, the Kaska Dena Council and Liard First Nation effectively won the same rights when the Yukon government signed two similar mineral agreements.)

In 2015, all parties – the Yukon government, the Kaska Dena Council, and the Liard First Nation – agreed to negotiate a deal. But according to the Yukon government, which says multiple First Nations’ overlapping claims preclude an easy solution, talks broke down in January.

|

|

Map courtesy of Yukon Energy, Mines and Resources

|

According to Dave Porter, lead council for the Kaska Dena Council and Liard First Nation, the Kaska feel that “the process of free entry staking is a direct violation” of section 35 of the Canadian constitution, which affirms and recognizes the existence of indigenous rights. Over the years, the courts have been defining precisely what those rights involve. And the thrust of recent decisions – including the 2014’s Tsilhqot’in decision – have swung the pendulum, giving First Nations more power in determining the outcome of development projects on their traditional territory.

Free entry staking, Porter went on, “creates a third party interest” that affects aboriginal title, and at a minimum “triggers a duty to consult and accommodate.”

In total, the Kaska staking bans cover 23 per cent of the Yukon. With known zinc and tungsten deposits, the affected area is mineral rich.

Noting that many prospectors are First Nations and that the Kaska are not averse to mining, Porter said that the Kaska Dena Council is willing to agree to a temporary lift of the ban – as long as they feel confident that the Yukon government is serious about negotiations.

Negotiations, said Porter, broke down because government negotiators were not given the power to conclude a deal by government leadership. “It came down to a lack of mandate for the negotiators,” explained Porter. “Given their mandate, we could not see our way to an agreement.”

In November the Yukon government changed hands for the first time in 14 years, and Porter said he is heartened by the signals the new Liberal government has sent when it comes to its relationship with First Nations. “All of the indicators from the new government have been positive – but we’re still waiting for them to contact us and let us know they’re ready to negotiate,” said Porter, who noted that the three-month deadline on the second ban is fast approaching.

“From my perspective the most practical way to go forward is for the Yukon government and the Kaska to sit down and reach an understanding to resume the negotiations,” said Porter, who added that if an agreement is not struck and the Yukon government does not adhere to the court ruling to “consult and accommodate,” his clients will be forced to pursue litigation – a process that could halt staking indefinitely.

According to Yukon energy, mines and resources minister Ranj Pillai, an interim agreement with Liard First Nation and the Kaska Dena Council is a priority of his government. In the long term, he says he is aiming to strike a deal that balances the interests of Kaska, industry and Yukoners.

While he said he is hopeful he will make one, he “is not going to make any promises that we’re going to fix this in 90 days. I hope it happens, but I’m not going lead anyone on.”

The challenges, he said, boil down to three key issues: identifying traditional territory, resolving overlapping territorial claims among First Nations and categorizing the land (figuring out who has the rights to what). According to an interview Pillai gave to the CBC in early February, a number of different groups with overlapping claims are affected by any decisions the government makes and the Kaska have been resolute in their assertion that they have title over 100 per cent of their traditional territory. When it comes to the future of the territory, however, Pillai is adamant that mining will continue to play a central role in the economy and that the Yukon is poised to enter “the most robust time we’ve seen in history when it comes to mining.”

While relations between government and Kaska face challenges, both Pillai and Porter said the Kaska are working with miners to bring existing projects to fruition.

Golden Predator, a junior company that has been working with the Kaska to get its 3 Aces project off the ground, has proven itself to be “honest and open” and willing to “put a fair share of wealth on the table,” said Porter.

But for prospectors like Ron Berdahl, the bans are a deep source of frustration. Combined with pre-existing staking bans, 52 per cent of the Yukon is currently off limits to staking.

The Ross River staking ban extension, said Berdahl – who serves as president of the Yukon Prospectors Association – simply represents “one more domino in a long line of dominos that have already fallen.” While Berdahl has held properties within the Ross River area since the 1980s, he has not been able to explore them since the court decision.

For Berdahl, the long term prospects for prospecting in the territory look good – but when it comes to the near term, he is less optimistic. He worries that he will not be able to work his Ross River properties anytime soon and that Yukoners – indigenous and non-indigenous alike—will miss out on the next big boom.

“It’s sad to see something like a staking ban ruin an opportunity for this territory,” he said.

Speaking for himself, Berdahl said he wants to see government “quit fighting” with First Nations. “It’s very obvious that the courts have decided that First Nations have control over most things that happen in their traditional territory, and I think industry should back the First Nations 110 per cent.”

*****

This was one of our favourite stories of the year. To see the full list, check out our Top 10 of 2017 editors' picks.