At the end of May, the Renard processing plant had all major equipment and process controls installed. All images courtesy of Stornoway Diamonds

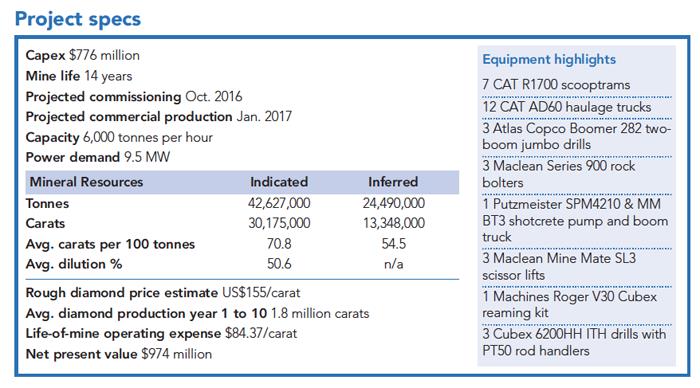

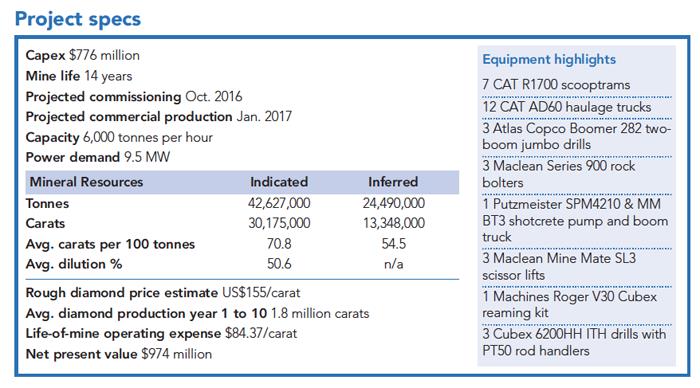

The Renard mine sits in the James Bay region of Quebec, about 250 kilometres north of Mistissini. Soon after acquiring the project in 2007, Stornoway took advantage of provincial programs to support mineral development. Quebec’s flow-through share program funded its exploration during the credit crisis, and by the time the province’s ambitious northern development program Plan Nord launched in 2011, Renard was one of the star properties justifying regional infrastructure investment by the province. The feasibility study released that year anticipated an 11-year mine life based on a Probable Mineral Reserve of 18 million carats. An updated mine plan, released in March, extended the life of mine to 14 years, following an increase in the reserve to 22.3 million carats.

Stornoway joined other mining companies and communities to plan an all-season gravel highway. The first project approved under Quebec’s Plan Nord initiative, it extends Route 167 northward by 260 kilometres and “makes Renard the only diamond mine in Canada with an all-season road,” according to Matt Manson, Stornoway’s CEO. The company used a $77-million loan from the province to build the last 100 kilometres and put in an airport to fly employees and contractors in and out.

With the road completed in 2013, Stornoway raised its entire capital budget in time to start construction in July 2014. Manson said: “We were able to say to investors, ‘Listen, everything’s done, the road is in, the airport is in, permits are in place, we’re ready to go. We just need the money.’”

The total capital to take Renard to commercial production comes to $776 million. Without the road, there would have been a mere six-week winter shipping window and all the overbuilding, overstocking and potentially expensive errors that would entail.

Having the road not only made just-in-time deliveries possible, it also enabled an innovative power source: liquefied natural gas (LNG). “Being the first diamond mine in Canada with a road allowed us to be the first mine in Canada with an LNG power plant,” said Manson. Tapping into the electrical grid would have cost about $170 million for infrastructure, so the 2011 feasibility study called for traditional diesel generators. But with the road, LNG can be trucked in daily from Montreal and used in a Caterpillar-supplied gensets at a cost of 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, compared with 30 cents for diesel.

An all-season road, shown here under construction in 2012, solved many of the logistical challenges that Canada’s other diamond producers still must contend with.

Large diamond recovery

Renard can chalk up another distinction: first diamond mine in the world to include large diamond recovery (LDR) in the primary flowsheet. “The standard method of calculating grade and value for a diamond deposit assigns only a very nominal estimate of revenue for diamonds above 10.8 carats in size,” said Manson. But one of the project’s kimberlites – Renard 2, which accounts for the bulk of production in the first ten years – has the potential for larger stones. The samples collected so far predict that for every 100,000 carats, there could be one or two stones more than 100 carats in size and three to six stones that could be between 50 to 100 carats. At full production, Renard would recover 100,000 carats every few weeks.

Other mines with a coarse size distribution are plentiful worldwide, but Manson said they tend to install the technology to recover large stones only after losing some to breakage in the normal crushing circuit. “Because we have this potential,” said Manson, “and because it’s potentially a material impact on our revenue – we’re talking about some big numbers here – the plant is being designed from day one to recover those diamonds, should they exist.” He stressed that while size could be predicted, quality could not; Stornoway is not making any public estimates as to the added revenue that large diamonds could net. Any large diamonds would be “gravy.”

After a cone crusher breaks the ore down to under 45 millimetres, anything over 19 mm cycles through the LDR circuit, an x-ray transmission machine supplied by European company TOMRA. “The TOMRA XRT machine is essentially a high-speed belt that takes large amounts of ore,” said Manson. “You are blasting with air anything that fluoresces with x-rays.”

The rest of the mining and processing setup is standard for diamond mines. Three kimberlites will be mined in the first decade, using a combination of open pits and (as of 2018) an underground ramp. Between 1.5 million and three million tonnes of ore will head to the process plant annually; the nameplate capacity of the plant is 6,000 tonnes per day. After the first round of crushing and the LDR circuit, there is a recrush, dense media separation to produce concentrate, another recrush between high-pressure grinding rolls, and another round through the dense media separator.

Stornoway postponed a planned shaft to cut costs in its 2013 feasibility update. The ramp corkscrews around the planned future location of the shaft down to a depth of about 700 metres, the base of the Indicated Resource. Once it becomes prohibitively expensive to use the ramp at depth, Manson said the shaft will go in. Renard’s kimberlite pipes seem to depart from the typical carrot shape; one of them measures the same width 1,000 metres below ground as it does at surface, providing strong incentive to build deeper infrastructure. “But that’s a pretty long way out there,” he said. “We can worry about it then.”

The mine will generate electricity using liquid natural gas, which provides a deep discount compared to diesel.

Waste and water management

To deal with its tailings, Renard opted to build a dry stack facility – partly for lack of an alternative.

“In the mid-2000s, the federal government decided to rewrite the standards by which it would permit the deposition of mine tailings in water bodies,” explained Manson. “So they ripped up all the existing standards and they began creating new standards for the mining industry. They did base metals, they did gold and precious metals. But in 2008, when the credit crisis hit, De Beers Canada decided to temporarily suspend production at Snap Lake and the Victor Mine, and the federal government used that as an excuse to cut the funding to the team at the Ministry of the Environment who were rewriting the standards for the last mining sector, which was diamonds.”

Still without standards in 2011, Stornoway could not obtain a permit for its first choice, a valley with a stream. “So we then chose, as a strategy, to do a dry stack,” said Manson. “Lucky for us, our tailings don’t have any metals in them. There’s no sulfides in the rock so there’s no acid-generating potential. So after all the tests, it was concluded that we could do that quite cheaply.”

Martin Boucher, vice-president of sustainable development at Stornoway, pointed out that the dry stack solution has inherent advantages: no dams and berms to build; reduced demand for fresh water; and a lighter post-closure responsibility. “When you’re forced to develop new ideas, most of the time the final decision is better,” he remarked.

In other ways, Stornoway sought to get out ahead of the government. Current federal and provincial water management rules only require that the runoff from waste storage facilities be collected and treated, but Boucher foresees more comprehensive rules coming down the pike. “We hate surprises,” he said. “It is way cheaper to design your site and do it during construction than after. After, it costs two to three times more.”

So Stornoway spent a little extra to build a system of drainage ditches surrounding the entire mine site. “Every drop of precipitation, snow or water, that lands on the site gets collected in these ditches, sent to a water treatment facility, and treated to remove suspended solids before it’s released into the environment,” said Manson.

The Renard project also reevaluated its plan for domestic sewage treatment in anticipation of more stringent federal rules about toxins. After sitting down with two consultants and a budget for one day, Boucher’s team switched from an aerated lagoon to a series of membrane bioreactors that produce drinking-quality water.

Ramp development for the underground mine extended 1,635 metres at the end of May. In the fall, underground progress will accelerate with the addition of a second development team.

Good timing

Building all of this has gone very quickly. The depressed mining market, according to Manson, makes it easier to find quality local suppliers and contractors who can work within Stornoway’s budget and are available immediately. “Between the Rainy River project in Red Lake, Ontario, and the Atlantic, we’re the only mine under construction,” he said.

The same is true of global procurement. Caterpillar is supplying the mine’s mobile fleet. “When we did our feasibility study in 2011, the lead time for Caterpillar equipment was about eighteen months,” said Manson. “Now, the lead time for their mining trucks is a few weeks.”

Speedy contracting and procurement shaved three months off Renard’s construction schedule. Another month has been saved by pure productivity. One month set aside for risk also appears unnecessary. Stornoway expects Renard to be producing at 60 per cent of nameplate capacity by December 31, 2016, five months ahead of schedule. As a result, the initial capital budget has dropped from $811 million to $776 million.

Life-of-mine operating costs are expected to be $56.20 per tonne, or $84.37 per carat. Stornoway estimated a 59 per cent operating margin in its 2016 update, which revised the rough diamond price downward to US$155 per carat in response to market conditions. The second half of 2014 and 2015 saw a significant drop in spot prices, widely attributed to slowing consumer demand. There were, however, more positive signs in 2016; the gem industry information service Rapaport, identified a first-quarter increase in dealer demand and in the price of polished diamonds, while De Beers inched its asking price back up. De Beers CEO Philippe Mellier suggested a “fragile recovery” in an interview with the Financial Times.

“Everybody wants to build their projects in the down cycle and mine them in the upcycle, and we raised all of our money in spring of 2014,” said Manson. “We are the poster child for good timing in the mining business. We hope. Right?” He laughed. “We’re certainly hitting the down cycle for construction. We’re hoping we’re going to hit the upcycle in terms of the pricing of our commodity.”

As long as Renard can withstand some volatility, Manson is not worried. He sees stability in the cultural value of diamonds and in the relative difficulty of adding new mines. “Diamonds are genuinely hard to find,” he said. “And it takes a long time to bring a new diamond mine to production. Our mine was 16 years from discovery to production.”

An all-season road, shown here under construction in 2012, solved many of the logistical challenges that Canada’s other diamond producers still must contend with.

An all-season road, shown here under construction in 2012, solved many of the logistical challenges that Canada’s other diamond producers still must contend with. The mine will generate electricity using liquid natural gas, which provides a deep discount compared to diesel.

The mine will generate electricity using liquid natural gas, which provides a deep discount compared to diesel. Ramp development for the underground mine extended 1,635 metres at the end of May. In the fall, underground progress will accelerate with the addition of a second development team.

Ramp development for the underground mine extended 1,635 metres at the end of May. In the fall, underground progress will accelerate with the addition of a second development team.