The metallurgical team managing the plant at South Carolina’s Haile gold mine, above, adopted an automated approach to metallurgical reporting, which frees them up to focus on process improvements. Courtesy of Caelen Anderson/OceanGold

There is a story developing in processing plants. It began slowly over the last decade as the high-grade material got mined and the sector wrestled with having to dig deeper and work harder to extract ore. Operating costs skyrocketed until global economic pressures put the squeeze on everyone. The resilient miners got smarter to improve their plants’ efficiencies and abilities to handle lower and more variable ore grades. They turned to instrumentation to measure and automate, step by step, control loop by control loop. But the tools that first gave marginal gains have begun to show a fuller potential. All this instrumentation – and the data it collects – does not just allow miners to improve their plant’s efficiencies within the same old way of doing things. It is a gateway to a whole new approach with faster, smarter, more productive and efficient processing that eliminates the manual guesswork and enables operators and metallurgists to run their operations with precision and accuracy. It is a digitalized future of opportunities in real time. And from needing much convincing to adopt new technologies, miners who have had the Eureka moment are suddenly developing the technologies themselves or seeking them out to improve their plant performance.

Analyze the feed with speed

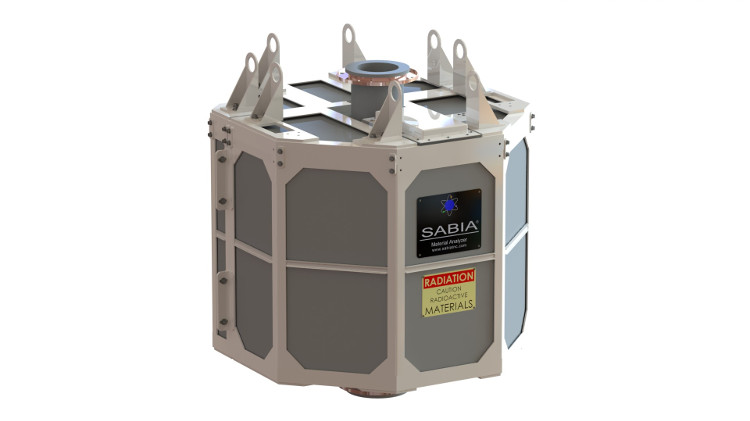

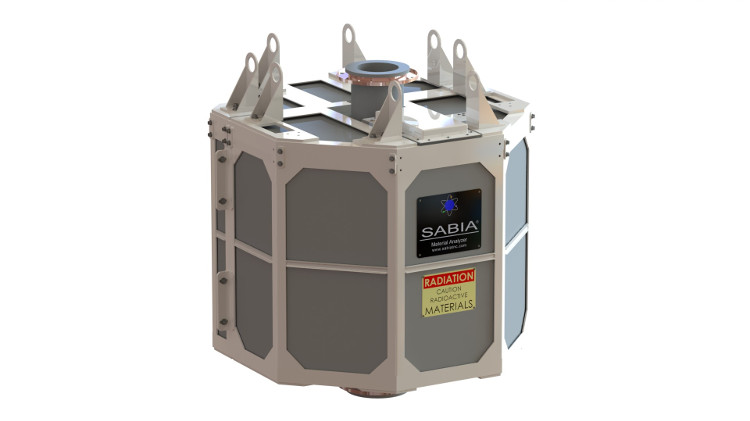

Sabia Inc. has been seeing a rush of interest recently in the Prompt Gamma Neutron Activation Analysis (PGNAA) slurry analyzer it developed in 2009 and installed in Glencore’s Sudbury Integrated Nickel Operations in 2014, said April Montera, sales director for Sabia. “It’s the first and only on-pipe slurry analyzer,” she said.

While previous slurry analyzers were based on sampling, Sabia’s patented PGNAA analyzer measures 100 per cent of the incoming feed on a pipe or conveyer belt in real time. The analyzer works by sending neutrons to the mined material and these are captured within its atoms. The atoms then give off gamma rays which are measured by the elemental analyzer. This allows operators to adjust their flotation based on the exact elemental breakdown of feed in real time, either manually or automatically. They can add a second or third analyzer to analyze 100 per cent of the final product and confirm their process is optimized.

The on-pipe slurry analyzer from Sabia Inc. measures the feed flowing past in real time. Courtesy of Sabia Inc.

The applications for the analyzer are vast. “We’ve already had success with nickel and phosphate and gold,” said Steve Foster, Sabia’s chief technology officer and one of the developers of the analyzer. “But from silver to copper, zinc and everything in between, the analyzer works fabulously.”

The analyzer, which is web browser-based, allowing for remote monitoring, is also a powerful gatherer of valuable data for deeper analysis and optimization.

Digestible data

The increase of implementation in plants has empowered metallurgists with a mountain of valuable data to help them solve problems and improve plant performance. Having all that data is the upside. The downside is the amount of work it takes them to access it and build reports.

“A lot of engineers become simply administrators, generating Excel reports every day and don’t actually get to do their job, which is to analyze the plant and make improvements,” said John Vagenas, managing director of Sydney, Australia-based Metallurgical Systems.

In response, he developed an advanced process plant information system called Metallurgical Intelligence, which automates metallurgical accounting and identifies relationships between variables to solve problems and optimize. “Inherently, everything in mining is multi-variant,” said Vagenas. “Very rarely is there a simple linear relationship between two things.”

Vagenas designed the system as a metallurgist to resolve the challenges he had experienced or noted through his years of work in the field. The system centralizes all the data in the plant, which allows it to crosscheck the data, flag instrumentation errors and keep accurate detailed records for transparency and validation. It also helps identify mine to mill errors and the correct solutions. The approach is to use dynamic simulation that builds a virtual plant, so that all elements and components can be tracked, and the time lag dependency of the process included in the calculations. Reports are available online for convenience. In the last year, his system has attracted a growing stream of new customers. “It’s like most overnight success stories: ten years in the making,” he said.

“Metallurgical Intelligence has a lot more to offer than other systems,” said Caelen Anderson, metallurgical superintendent for OceanaGold’s Haile gold mine in South Carolina, which began operations in 2017 and is using the system. “With some, you get your own platform and report online but they don’t have all the functionality. Instead of pulling in and finding data to go into an Excel sheet, with this, I already have all the data and I have a dynamic model of the plant and my time is spent making sure that it accurately reflects what’s going on in the plant so we can make decisions based on that, which is a lot better than just trying to find the data.”

With a hierarchical menu that includes each area of the plant, the system allows engineers to drill down on the data to make calculations, but it is also simple to use for non-metallurgists. “If our general superintendent is on call for the weekend, the system is easy enough that, if he needs to, he can log in and see the control panel,” said Anderson. “It’s very simple and colour coded.”

Central control

Just as with data, the increase of instrumentation in plants has an upside and a downside, at least if the goal is to achieve the optimal performance and improvements. The upside is more comprehensive measurements and responsive control. The downside is that because of the interconnectedness of everything in a plant, a careful design is needed to get the most out of instrumentation, said Nicolas Lazare, manager of process control for Expert Process Solutions (XPS).

“If the instrumentation is not properly selected and used, you are not able to get good measurements to control properly. You might have the best instrument on the market but if it is not well installed and calibrated, it may not deliver a good measurement,” said Lazare. “Or you may want to create very complex process controls when it’s not required and a more appropriate solution exists.”

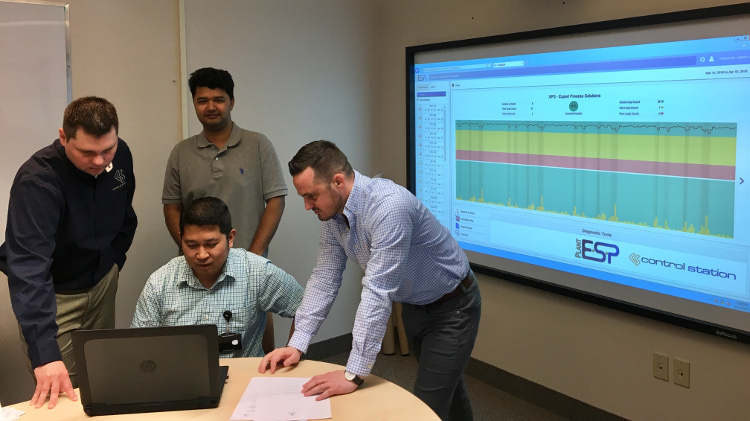

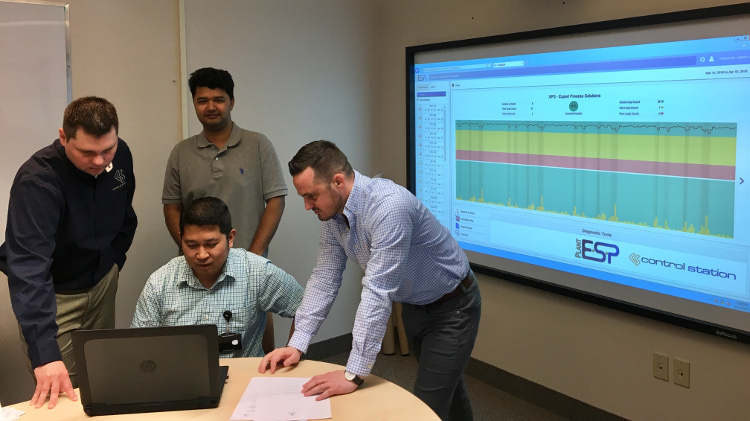

The team at the XPS Technology Centre in Sudbury, Ontario, have the ability to capture and analyze process data generated at operating sites around the world. Clockwise from the top: Naseeb Adnan of XPS, Jon Stevens of Control Station, Napoleon Reata of XPS and Robert Rice of Control Station. Courtesy of XPS

The challenge for many plants typically lies not in the technology but in the lack of resources to monitor, calibrate and maintain all the control loops and instrumentations, said Dominic Fragomeni, vice-president at XPS. “You need people with the right skillset to maintain the hardware, the software and systems to capture the data and turn it into information to make a decision.”

It is not that the plants do not have such people, it is that “they are usually dealing with the day-to-day challenges, so it’s nearly impossible to have deep monitoring if you have 100 to 1,000 loops in the plant,” said Lazare, who developed a new service model that provides the deep monitoring for a list of a plant’s most critical 30 measurements remotely by XPS. “The important concept around this service is the permanent contact with the clients, as we want to help them to identify new gain or optimization opportunities, to maintain health of the control loop over time and not just create other KPIs,” said Lazare. At this point, five plants from around the world have signed up. The deep monitoring also provides deep analysis.

“The plants are all collecting data, but there is seldom the time and the tools to turn that data into information for decision making. So that’s where we come in,” said Fragomeni.

A new generation of technology – and people

Haile’s Anderson, who is 32, believes the use of high tech for plant improvement will continue to escalate. Today, “in mining, there is a large older generation and an up-and-coming younger generation, and there’s very few between,” he said. “There is a big age gap between the senior management and the people on the ground on the site. So as younger and younger people are getting into the positions where they say, ‘yeah, we’ll try that,’ I only see this growing.”