The primary crusher and ore conveyor. Materials from the operation were either recycled, sold to another mine operation or donated through local community groups. All images courtesy of Goldcorp

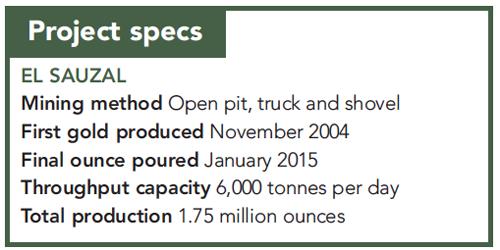

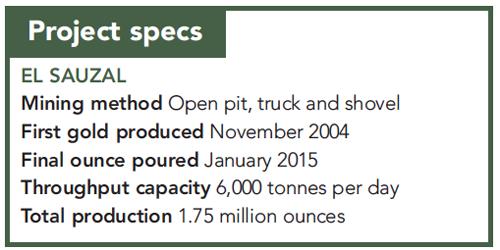

In December 2015, Goldcorp’s El Sauzal gold mine in Mexico became the first mine decommissioned under the International Cyanide Management Code (ICMC). Among signatories to the code, that was a milestone; to Goldcorp, it was one of the many essential ingredients in a well-planned closure.

In December 2015, Goldcorp’s El Sauzal gold mine in Mexico became the first mine decommissioned under the International Cyanide Management Code (ICMC). Among signatories to the code, that was a milestone; to Goldcorp, it was one of the many essential ingredients in a well-planned closure.

Back in 2008, El Sauzal was the first mine in Mexico to be certified in full compliance with the ICMC, which mandates triennial audits to ensure the mine is following protocols for safe transport, use and disposal of cyanide. A certified mine undergoing closure can simply withdraw from the code, as the ICMC does not in fact apply to decommissioned mines. But Chris Cormier, general manager of reclamation operations at Goldcorp, said the company chose to have its decommissioning process audited to support the code’s intention.

“We think it’s the right bookend to have if you’re going to manage the cyanide life cycle,” he said. “When it comes to cyanide, closure is just as important as startup in ensuring you’ve treated the environment and process correctly, so I think it’s just a natural fit.”

In operation, El Sauzal was an open-pit mine with a milling circuit followed by cyanide leaching; carbon-in-pulp processing; adsorption, desorption and recovery; and refinement into doré bars. Tailings went through a cyanide destruction circuit which included Caro’s acid and the INCO sulphur dioxide process and were then pressure filtered, leaving only negligible cyanide in the pore water, before being transported to a dry-stack facility.

El Sauzal mine in 2011 viewed from above with the processing plant top centre and the tailings stack descending on the left.

The 2015 audit verified that El Sauzal had disposed of its remaining cyanide so thoroughly that the code requirements had become irrelevant. That work took place between December 2014 and July 2015.

Cormier added: “There was minimal reagent cyanide supplies in the plant when we actually shut it off because you reduce your inventory as you near decommissioning. The cyanide remains in the containers it was delivered in and can be sent back to its manufacturer.” Goldcorp reported all planned shipments to Mexican regulators and tracked its progress back to its supplier, The Chemours Company.

However, residual cyanide needed to be rinsed out. The emptied cyanide mixing and storage tanks were washed using caustic soda and sodium hypochlorite, and the rinse water was pumped out to the leach tanks. The leach tanks continued to feed the tailings filtration plant until all solid tailings had been filtered and water and neutralizing compounds were then pumped in a closed circuit through most of the process equipment over a several week period. Goldcorp did not consider the filters in need of rinsing as these followed the cyanide destruction circuit, with the auditor in agreement.

The wash water was directed to a lined containment pond, where sunlight further broke down any remaining cyanide. This water was then monitored until it met safe discharge limits, before being discharged to the dry stack and allowed to evaporate.

This work was all done entirely by Goldcorp employees familiar with the practices and requirements of the ICMC. Colorado-based Visus Consulting Group visited the site and, before reviewing Goldcorp’s sampling data, interviewed staff about their process and ultimately concluded that, by the ICMC definition, El Sauzal had successfully been decommissioned.

The same site is pictured, viewed from the opposite direction, with the tailings stack in the centre, the mill site lower right and a diversion ditch running through the middle.

Back to nature

Of course, disposing of cyanide was only a small part of the process to remediate an entire open-pit mine. Goldcorp chose to return the site to a natural state similar to its surroundings, the Sierra Madre of Chihuahua above the Urique River, with the biggest concern being its ability to withstand heavy rain, which averages 250 millimetres in July.

“Really, it’s about the ultimate movement of water on the site and what kind of vegetation the particular landform can support,” said Cormier. “You’re dealing with the side of a mountain where there are landslides, and there are ravines from water running through from hundreds and thousands of years of wear and tear. So you look at the overall landscape you have and you design that structure to best withstand the conditions you can expect over the next 50, 100, 500 years.”

Goldcorp hired regional contractor ICSA (Ingeniería de ciudades S.A.) to construct over six kilometres of diversion channels around the site. Engineers studied the existing underfoot conditions, water velocities, turns and intersections in different areas to identify the least erosive paths possible. About half of these channels are reinforced with a lean mix concrete.

Quite a lot of water can build up from one mountain collection area to another and some channels are more than four metres wide and built to handle water from up to three kilometres away. “Obviously it’s not going to handle water like that all the time,” added Cormier, “but we did design it for sporadic peaks, and hence some of our ditches are quite wide.”

The tailings facility was recontoured, creating a hillside that leads into a flatter area with topographical diversity to support different vegetation and fauna. Waste rock or alluvial materials were used to cap the tailings to prevent oxygen and water infiltration; the capping ranged from half a metre in some places to 10 metres or more in others.

Most of the reclaimed area was either seeded or planted over with native plants. Over the last few years of the mine’s life, Goldcorp employees collected specimens and propagated these in nurseries. The native plants included guinolo, an abundant shrub that often repopulates disturbed habitats; amapa trees with bright yellow or pink trumpet-shaped flowers; and Mexican logwood, a tropical hardwood with medicinal uses.

The mill and shop facility

Dismantling the mine

The newly recontoured, revegetated site bears little trace of the process plant, waste dumps, offices, shops, airstrip and employee camp that used to populate it. All of that had to go.

“The equipment you can sell,” said Cormier. “Our key partner in site decommissioning was Timmins Gold, as it purchased the mill site and other facilities for use at another property.” Another contractor, Inpromine, also participated in removing equipment and buildings.

Goldcorp sold most material used to construct the site, either for reuse or as scrap. Some items, including building materials, office equipment and a trailer, were donated through local community groups.

All hazardous waste was removed and sent to a storage facility elsewhere in Mexico and waste dumps were resloped and revegetated as safety allowed. The ground where any other infrastructure had stood was also reseeded, or replanted.

Location and logistics

El Sauzal’s remote location made logistics a challenge. “You can’t run down to the corner store to get something, and similarly you can’t expect a truck to leave site and return in an hour,” said Cormier.

The ore stockpile

“Kudos to the groups that were out there working at the end,” said Cormier. “As people had to start to live in tents and campers for the last little period, it made conditions more challenging than it would have been during operations, but I’d say lots of teams worked extremely well together in communicating different aspects of the work.”

In order to access the main highways, freight needed to travel through a number of small communities not familiar with traffic. Goldcorp and its contractors alerted local stakeholders to let them know what, how much, and when material would be passing through the different areas. The roads were also kept well maintained, with much of that work undertaken by Timmins Gold through contractors.

Cormier said there were no cost-related tradeoffs required; El Sauzal’s management designed the project plan, requested a budget to meet this plan, and received its requested budget in full with a sizable portion of the company’s $57 million spent on closure and reclamation last year going to El Sauzal. “Smart investment up front is always going to minimize your cost and maintenance in the long term,” Cormier pointed out.

Monitoring

El Sauzal is now in its “long-term” phase of existence. Reclamation work was completed in summer 2016, but Goldcorp will spend at least another few years monitoring water quality on the Urique River, assessing the stability of the new landforms, and monitoring revegetation.

“We’ll continue that until we’re comfortable that the site has performed as we’ve designed and expect it to,” said Cormier.

Prior mine planners’ decision not to store tailings with a water cover “certainly made that facility much more simplified to close on a permanent basis,” he said, before adding that tailings need to be stable no matter what kind of tailings it is.

“It’s how you design the entire closure to work as a single unit. When you leave, the entire landform has to work together. We looked at the entire El Sauzal site as a system and a landform that’s going to be there for many hundreds of thousands of years and our design focused on the best way we could close the site in a responsible manner – which I think we did.”

Mining by the code

The International Cyanide Management Code is a program formed in 2005 to encourage safe cyanide use among gold mining companies. Alarmed by a disastrous cyanide spill at a Romanian gold mine, stakeholders from industry, environmental and financial spheres created an industry-funded nonprofit, the International Cyanide Management Institute (ICMI). The ICMI drafted the original Code and continues to provide oversight, code revisions and training.

When a mining company applies to be a signatory to the Code, it agrees to abide by guidelines for cyanide storage, accident prevention, health and safety, public reporting and more. An independent audit is required within the first three years at every mine site that uses cyanide, and every three years thereafter. The results are published online. A mine certified under the Code must only use cyanide suppliers and transporters that have also signed on to the Code.

Participation in the program is completely voluntary. Its current roster of signatories includes 45 mining companies, 22 cyanide producers, and 118 transporters.

In December 2015, Goldcorp’s El Sauzal gold mine in Mexico became the first mine decommissioned under the

In December 2015, Goldcorp’s El Sauzal gold mine in Mexico became the first mine decommissioned under the  El Sauzal mine in 2011 viewed from above with the processing plant top centre and the tailings stack descending on the left.

El Sauzal mine in 2011 viewed from above with the processing plant top centre and the tailings stack descending on the left. The same site is pictured, viewed from the opposite direction, with the tailings stack in the centre, the mill site lower right and a diversion ditch running through the middle.

The same site is pictured, viewed from the opposite direction, with the tailings stack in the centre, the mill site lower right and a diversion ditch running through the middle. The mill and shop facility

The mill and shop facility