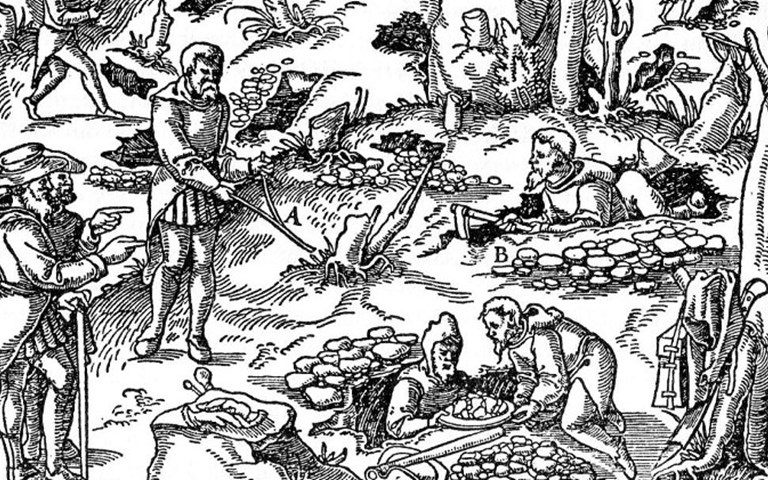

The work involved in creating 289 detailed woodcut illustrations delayed the publication of De Re Metallica until after Bauer’s death in 1556. The illustration above, from Book XII, depicts prospecting work. Wikimedia/Geoz

George Bauer, a scholar of classics, philosophy and languages, moved to the mountains of Bohemia, in the present-day Czech Republic to take a post as a physician in the town of Joachimsthal. When he arrived in 1527, the region was a booming mining camp, which included a silver mine that produced three million ounces annually. What Bauer began to learn there set both the course for his intellectual life and the foundation for the next 200 years of the mining and metallurgy industries.

Bauer was born in Saxony in present-day Germany in 1494. After studying at the University of Leipzig and a short career as a school teacher, he returned to university to study medicine in Bologna, Venice, and Padua. He was initially drawn to the mines of Joachimsthal hoping to discover medical drugs from ore but soon shifted his focus. He spent his free time visiting the town’s mines and smelters and eventually quit his job to observe the industry full-time. In 1533, Bauer moved to Chemnitz in Saxony, also a prolific mining town, where he resumed a post as a town physician and remained for the rest of his life.

The explosion of mining activity in the regions of Saxony and Bohemia was a result of an increased European demand for metals in the late Middle Ages. Silver was increasingly bought and sold as a commodity as well as being used as money. Coins made from Joachimsthal silver were known as “thalers” – the original dollar.

In 1533 Bauer started writing De Re Metallica, his seminal treatise on mining and metallurgy. While it was completed in 1550, he did not send it to publishers until 1553 and the 12-volume series of books was not published until a year after his death in 1556, due to the work involved in creating 289 detailed woodcut illustrations to accompany the text.

De Re Metallica, published under the Latin version of Bauer’s name, Georgius Agricola, remained the standard textbook on mining and metallurgy for more than 200 years and earned Agricola the moniker the “father of mineralogy.” Churches chained copies to their altars, so priests could translate parts of the Latin text to their miner congregations.

RELATED: McGill University's George Demopoulos talks about the shift in universities from metallurgy programs to materials science and engineering, and what that means for the industry

In De Re Metallica, Agricola rejected the views of many “fraudulent” alchemists and pioneered a new approach to scientific writing, where his conclusions were based on observation and field experience rather than dogma or conjecture. Mining engineer and former United States president Herbert Hoover, who spent five years translating De Re Metallica into English in 1912 with his wife Lou, a geology major and an ex-Latin teacher, lauded Agricola as “the first to found any of the natural sciences upon research and observation, as opposed to previous fruitless speculation.”

The 12 books embrace all aspects of Renaissance mining, from practical advice for mine-owners (worship God, live on site, elect a second-in-command, own several properties), to legal advice for specific issues. He dedicated two books to finding veins, and another to the different tools and machines available to miners. Prospecting, mechanical engineering, processing and smelting ore, and the manufacture of salt, soda, alum, vitriol (used in medieval dyes, medicines and as a purifying agent in smelting), sulfur, bitumen and glass are all covered in detail.

Agricola provided detailed descriptions of cutting-edge 16th-century mining technology, including the use of water power for crushing ore and improvements in suction pumps and underground ventilation systems. These were becoming increasingly necessary as mine shafts were sunk deeper into the ground.

He also provided a detailed account of diseases and accidents most prevalent among workers, along with recommendations on how to prevent them. These included the “difficulty in breathing and destruction of the lungs,” caused by dust inhalation. Agricola’s focus on miners’ health and safety, inspired by his medical background, established the series as one of the first ever published occupational health handbooks.

Over the 200 years that followed, De Re Metallica was reprinted in a number of Latin, German and Italian editions. It remained a practical reference for many, given that the German mining technology it described was the most advanced and sophisticated in Europe.

The Hoovers’ translated English edition framed and contextualized the translated text with a glut of introductory material, alongside countless footnotes and appendices. It was serialized in a popular mining magazine based out of London, and won a Gold Medal from the Mining and Metallurgical Society of America.

The translation process was made all the more laborious because Agricola had invented countless Latin terms to describe medieval mining processes and pieces of equipment. Hoover and his wife had to decipher what he was describing by assumption and guesswork.

The Hoovers’ translation remains in print today as the only English version. It includes the woodcut illustrations found in Agricola’s original text.

*****

This was one of our favourite stories of the year. To see the full list, check out our Top 10 of 2017 editors' picks.